“And so when I began to go on evening walks last fall . . .” begins Julius, the perspicacious narrator of Teju Cole’s admirable and excellent début Open City. That opening “And” is significant, an immediate signal to the reader that this novel will refuse to align itself along (or even against) traditional arcs of plot and character development. We will meet Julius in media res, and we will leave him there, and along the way there will be learning and suffering and compassion and strange bubbles of ambiguity that threaten to burst out of the narrative.

As noted, Open City begins with Julius’s peripatetic voyages; he walks the night streets of New York City to ostensibly relieve the “tightly regulated mental environment of work.” Julius is completing his psychiatry fellowship at a hospital, and the work takes a toll on him, whether he admits it or not. In these night walks—and elsewhere and always throughout the novel—Julius shares his sharp observations, both concrete and historical. No detail is too small for his fine lens, nor does he fail to link these details to the raw information that rumbles through his mind: riffs on biology, history, art, music, philosophy, and psychology interweave the narrative. Julius maps the terrain of New York City against its strange, mutating history; like a 21st century Ishmael, he attempts to measure it in every facet—its architecture, its rhythms, its spirit. And if there is one thread that ties Julius’s riffs together it is the nightmare of history:

But atrocity is nothing new, not to humans, not to animals. The difference is that in our time it is uniquely well organized, carried out with pens, train carriages, ledgers, barbed wire, work camps, gas. And this late contribution, the absence of bodies. No bodies were visible, except the falling ones, on the day America’s ticker stopped.

Open City is the best 9/11 novel I’ve read, but it doesn’t set out to be a 9/11 novel, nor does it dwell on that day. Instead, Cole captures something of the post-9/11 zeitgeist, and at the same time situates it in historical context. When Julius remarks on the recent past, the concrete data of history writhes under the surface. He remarks that the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center “was not the first erasure on the site,” and goes on to detail the 1960s cityscapes that preceded the WTC. Before those, there was Washington Market. Then Julius embarks, via imagination, into the pre-Colombian space of the people we now call Indians or Native Americans. “I wanted to find the line that connected me to my own part in these stories,” he concludes, peering at the non-site that simultaneously anchors these memory-spaces.

Julius’s line, like the lines that comprise New York City (and perhaps, if we feel the spirit of its democratic project, America itself) is a mixed one, heterogeneous and multicultural. Julius’s father, now dead, was an important man in Nigeria, where Julius enjoyed a relatively privileged childhood. Julius’s mother—they are now estranged—is German. He remarks repeatedly about his German grandmother’s own displacements during WWII, reflecting at one point that, from a historical perspective, it was likely impossible that she escaped Cossack rape.

Even though he sometimes seems reticent to do so, Julius delves into the strange violence that marks his lineage. He recalls a childhood fascination with Idi Amin; as a boy, he and his cousins would watch the gory film The Rise and Fall of Idi Amin repeatedly: ” . . . we enjoyed the shock of it, its powerful and stylized realism and each time we had nothing to do, we watched the film again.”

Fascinated horror evinces repeatedly in Open City. In just one example, Julius believes he sees “the body of a lynched man dangling from a tree”; as he moves closer to inspect, he realizes that it is merely canvas floating from a construction scaffold. Perhaps so attuned to history’s grand catalog of spectacular atrocity, Julius finds it lurking in places where it does not necessarily evince.

In turn, despite his profession as psychiatrist, Julius is wary of human sympathy. Throughout the novel, dark-skinned men engage him by calling him “brother.” He almost always deflects these attempts at connection, and internally remarks them as fatuous, or naïve, or false. This is not to say though that Julius doesn’t make significant (if often transitory) connections.

One of the organizing principles of Open City comes in the form of Julius’s infrequent visits to the home of his former English professor, Dr. Saito, who is slowly dying. Saito’s own memories float into Julius—this technique repeats throughout the novel—and we learn that he was interned as a young man during WWII; the sad fact is another ugly kink in the line of American history that Julius attempts to trace.

Julius also befriends Dr. Maillotte, an aging surgeon on a flight to Brussels, where he spends a few weeks of Christmas vacation, ostensibly looking for his oma (a task he performs half-heartedly at best). As Julius daydreams, Dr. Maillotte, European émigré, finds a place within his vision of family members and friends:

I saw her at fifteen, in September 1944, sitting on a rampart in the Brussels sun, delirious with happiness at the invaders’ retreat. I saw Junichiro Saito on the same day, aged thirty-one or thirty-two, unhappy, in internment, in an arid room in a fenced compound in Idaho, far away from his books. Out there on that day, also, were all four of my own grandparents: the Nigerians, the Germans. Three were gone by now, for sure. But what of the fourth, my oma? I saw them all, even the one I had never seen in real life, saw all of them in the middle of that day in September sixty-two years ago, with their eyes open as if shut, mercifully seeing nothing of the brutal half century ahead and better yet, hardly anything at all of all that was happening in their world, the corpse-filled cities, camps, beaches, and fields, the unspeakable worldwide disorder that very moment.

In Brussels, Julius meets Farouq, an angry young man with intellectual, Marxist tendencies. Farouq believes in a theory of “difference” and finds himself at odds with both the dominant Belgian culture and with Western culture in general. Julius’s conversations with Farouq are a highlight of the novel; they help to further contextualize the drama of diaspora in the post-9/11 world. Later, Julius finds a counterweight to some of Farouq’s extreme positions over a late lunch with Dr. Maillotte, who suggests that “For people to feel that they alone have suffered, it is very dangerous.” There’s a sense of reserved moderation to her critique—not outright dismissal nor condemnation, but simply a recognition that there are “an endless variety of difficulties in the world.”

Julius seems to tacitly agree with Maillotte’s assessment. His reluctance to accept brotherhood based on skin color alone speaks to a deeper rejection of simplicity, of tribe mentality, of homogeneity; it also highlights his essential alienation. At the same time, he’s acutely aware of how skin color matters, how identity can be thrust upon people, despite what claims to agency we might make. In search of the line that will connect him to his part of the American story, Julius finds unlikely “brothers” in Farouq, Maillotte, and Saito.

But let us not attribute to Julius a greater spirit than Cole affords him: Open City is a novel rich in ambiguity, with Julius’s own personal failures the most ambiguous element of all. While this is hardly a novel that revolves on plot twists, I hesitate to illustrate my point further for fear of clouding other readers’ perceptions; suffice to say that part of the strange, cruel pleasure of Open City is tracing the gaps in Julius’s character, his failures as a professional healer—and his failures to remark or reflect upon these failures.

But isn’t this the way for all of us? If history is a nightmare that we try to awake from—or, more aptly in a post-9/11 world, a nightmare that we awake to, to paraphrase Slavoj Žižek—then there is also the consolation and danger that time will free us from the memory of so much atrocity, that our collective memory will allow those concrete details to slip away, replaced with larger emblems and avatars that neatly smooth out all the wrinkles of ambiguity. “I wondered if indeed it was that simple, if time was so free with memory, so generous with pardons, that writing well could come to stand in the place of an ethical life,” Julius wonders at one point; later, Saito points out that “There are towns whose names evoke a real horror in you because you have learned to link those names with atrocities, but, for the generation that follows yours, those names will mean nothing; forgetting doesn’t take long.” Julius’s mission then is to witness and remark upon the historical realities, the nitty-gritty details that we slowly edge out of the greater narrative. And Cole? Well, he gives us a novel that calls attention to these concrete details while simultaneously exploring the dangerous subjectivity behind any storytelling.

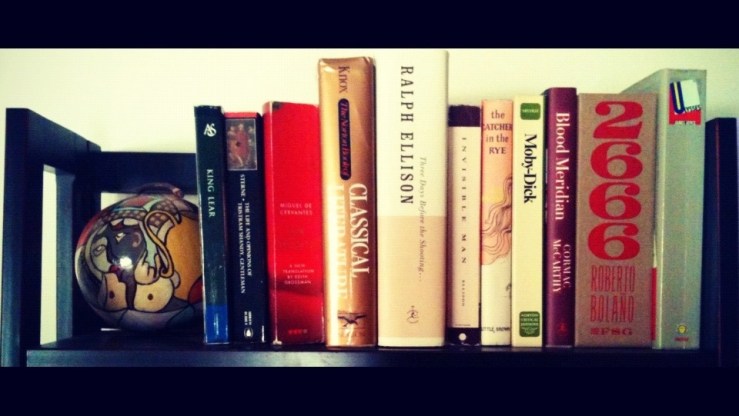

If it needs to be said: Yes, Open City recalls the work of W.G. Sebald, who crammed his books with riffs on history and melancholy reflections on memory and identity. And yes, Open City is flâneur literature, like Sebald (and Joyce, and Bolaño, perhaps). But Cole’s work here does not merely approximate Sebald’s, nor is it to be defined in its departures. Cole gives us an original synthesis, a marvelous and strange novel about history and memory, self and other. It’s a rich text, the sort of book one wants to immediately press on a friend, saying, Hey, you there, read this, we need to talk about this. Very highly recommended.

Open City is new in trade paperpack from Random House.