Composed in 1836, Georg Büchner’s novella-fragment Lenz still seems ahead of its time. While Lenz’s themes of madness, art, and ennui can be found throughout literature, Büchner’s strange, wonderful prose and documentary aims bypass the constraints of his era.

Let me share some of that prose. Here is the opening paragraph of Lenz:

The 20th, Lenz walked through the mountains. Snow on the peaks and upper slopes, gray rock down into the valleys, swatches of green, boulders, firs. It was sopping cold, the water trickled down the rocks and leapt across the path. The fir boughs sagged in the damp air. Gray clouds drifted across the sky, but everything so stifling, and then the fog floated up and crept heavy and damp through the bushes, so sluggish, so clumsy. He walked onward, caring little one way or another, to him the path mattered not, now up , now down. He felt no fatigue, except sometimes it annoyed him that he could not walk on his head. At first he felt a tightening in his chest when the rocks skittered away, the gray woods below him shook, and the fog now engulfed the shapes, now half-revealed their powerful limbs; things were building up inside him, he was searching for something, as if for lost dreams, but was finding nothing. Everything seemed so small, so near, so wet, he would have liked to set the earth down behind an oven, he could not grasp why it took so much time to clamber down a slope, to reach a distant point; he was convinced he could cover it all with a pair of strides.

Büchner sets us on Lenz’s shoulder, moving us through the estranging countryside without any exposition that might lend us bearings. The environment impinges protagonist and reader alike, heavy, damp, stifling. Büchner’s syntax shuffles along, comma splices tripping us into Lenz’s manic consciousness, his mind-swings doubled in the path that is “now up, now down.” We feel the “tightening” in Lenz’s chest as the “rocks skittered away,” as the “woods below him shook” — the natural world seems to envelop him, cloak him, suffocate him. It’s an animist terrain, and Büchner divines those spirits again in the text. The claustrophobia Lenz experiences then swings to another extreme, as our hero, his consciousness inflated, feels “he could cover [the earth] with a pair of strides.

And that baffling line: “He felt no fatigue, except sometimes it annoyed him that he could not walk on his head.” Well.

The end notes to the Archipelago edition I read (translated by Richard Sieburth) offer Arnold Zweig’s suggestion that “this sentence marks the beginning of modern European prose,” as well as Paul Celan’s observation that “whoever walks on his head has heaven beneath him as an abyss.”

Celan’s description is apt, and Büchner’s story repeatedly invokes the abyss to evoke its hero’s precarious psyche. Poor Lenz, somnambulist bather, screamer, dreamer, often feels “within himself something . . . stirring and swarming toward an abyss toward which he was being swept by an inexorable force.” Lenz is the story of a young artist falling into despair and madness.

But perhaps I should offer a more lucid summary. I’ll do that in the next paragraph, but first: Let me just recommend you skip that paragraph. Really. What I perhaps loved most about Lenz was piecing together the plot through the often elliptical or opaque experiences we get via Büchner’s haunting free indirect style. The evocation of a consciousness in turmoil is probably best maintained when we read through the same confusion that Lenz experiences. I read the novella cold based on blurbs from William H. Gass and Harold Bloom and I’m glad I did.

Here is the summary paragraph you should skip: Jakob Lenz, a writer of the Sturm and Drung movement (and friend and rival to Goethe), has recently suffered a terrible episode of schizophrenia and “an accident” (likely a suicide attempt). He’s sent to pastor-physician J.F. Oberlin, who attends to him in the Alsatian countryside in the first few weeks of 1778. During this time Lenz obsesses over a young local girl who dies (he attempts to resurrect her), takes long walks in the countryside, cries manically, offers his own aesthetic theory, prays, takes loud late-night bath in the local fountain, receives a distressing letter, and, eventually, likely—although it’s never made entirely explicit—attempts suicide again and is thusly shipped away.

Büchner bases his story on sections of Oberlin’s diary, reproduced in the Archipelago edition. In straightforward prose, these entries fill in the expository gaps that Büchner has so elegantly removed and replaced with the wonder and dread of Lenz’s imagination. The diary’s lucid entries attest to the power of Büchner’s speculative fiction, to his own art and imagination, which so bracingly take us into a clouded mind.

In Sieburth’s afterword (which also offers a concise chronology of Lenz’s troubled life), our translator points out that “Like De Quincey’s “The Last Days of Immanuel Kant” or Chateaubriand’s Life of Rancé, Büchner’s Lenz is an experiment in speculative biography, part fact, part fabrication—an early nineteenth-century example of the modern genre of docufiction.” Obviously, any number of postmodern novels have explored or used historical figures—Public Burning, Ragtime, and Mason & Dixon are all easy go-to examples. But Lenz is more personal than these postmodern fictions, more an exploration of consciousness, and although we are treated to Lenz’s ideas about literature, art, and religion, we access this very much through his own skull and soul. He’s not just a placeholder or mouthpiece for Büchner.

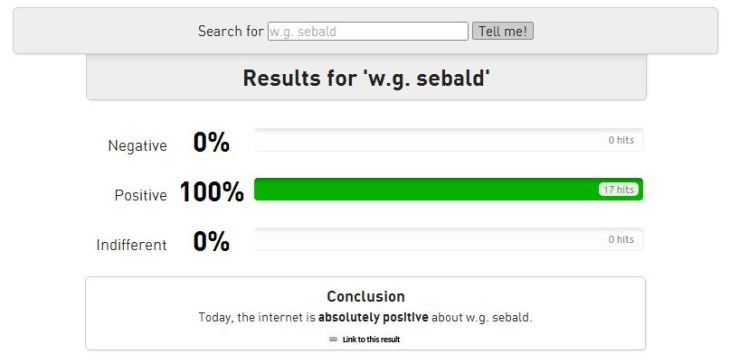

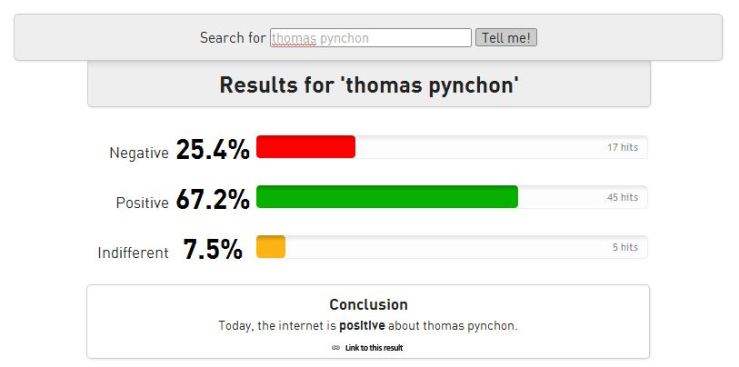

Lenz strikes me as something closer to the docufiction of W.G. Sebald. Perhaps it’s all the ambulating; maybe it’s the melancholy; could be the philosophical tone. And, while I’m lazily, assbackwardly comparing Büchner’s book to writers who came much later: Thomas Bernhard. Maybe it’s the flights of rant that Lenz occasionally hits, or the madness, or the depictions of nature, or hell, maybe it’s those long, long passages. The comma splices.

Chronologically closer is the work of Edgar Allan Poe, whose depictions of manic bipolar depression resonate strongly with Lenz—not to mention the abysses, the torment, the spirits, the doppelgängers. Why not share another sample here to illustrate this claim? Okay:

The incidents during the night reached a horrific pitch. Only with the greatest effort did he fall asleep, having tried at length to fill the terrible void. Then he fell into a dreadful state between sleeping and waking; he bumped into something ghastly, hideous, madness took hold of him, he sat up, screaming violently, bathed in sweat, and only gradually found himself again. He had to begin with the simplest things in order to come back to himself. In fact he was not the one doing this but rather a powerful instinct for self preservation, it was as if he were double, the one half attempting to save the other, calling out to itself; he told stories, he recited poems out loud, wracked with anxiety, until he came to his sense.

Here, Lenz suspends his neurotic horror through storytelling and art—but it’s just that, only a suspension. Büchner doesn’t blithely, naïvely suggest that art has the power to permanently comfort those in despair; rather, Lenz repeatedly suggests that art, that storytelling is a symptom of despair.

What drives despair? Lenz—Lenz—Büchner (?)—suggests repeatedly that it’s Langeweile—boredom. Sieburth renders the German Langeweile as boredom, a choice I like, even though he might have been tempted to reach for its existentialist chain-smoking cousin ennui. When Lenz won’t get out of bed one day, Oberlin heads to his room to rouse him:

Oberlin had to repeat his questions at length before getting an answer: Yes, Reverend, you see, boredom! Boredom! O, sheer boredom, what more can I say, I have already drawn all the figures on the wall. Oberlin said to him he should turn to God; he laughed and said: if I were as lucky as you to have discovered such an agreeable pastime, yes, one could indeed wile away one’s time that way. Tedium the root of it all. Most people pray only out of boredom; others fall in love out of boredom, still others are virtuous or depraved, but I am nothing, nothing at all, I cannot even kill myself: too boring . . .

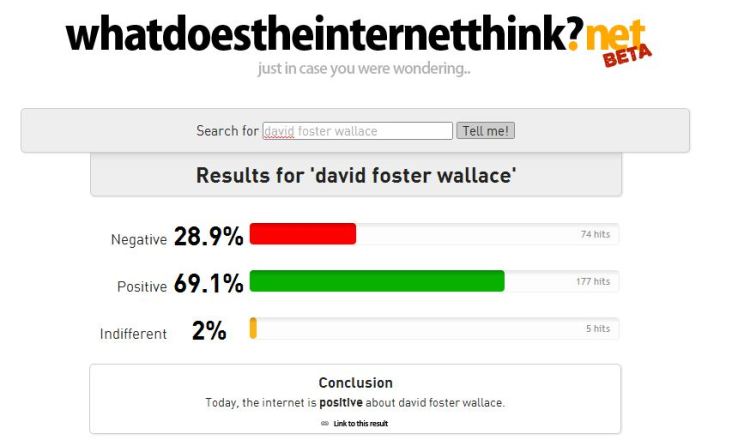

Lenz fits in neatly into the literature of boredom, a deep root that predates Dostoevsky, Camus, and Bellow, as well as contemporary novels like Lee Rourke’s The Canal and David Foster Wallace’s The Pale King.

Ultimately, the boredom Lenz circles around is deeply painful:

The half-hearted attempts at suicide he kept on making were not entirely serious, it was less the desire to die, death for him held no promise of peace or hope, than the attempt, at moments of excruciating anxiety or dull apathy bordering on non-existence bordering on non-existence, to snap back into himself through physical pain. But his happiest moments were when his mind seemed to gallop away on some madcap idea. This at least provided some relief and the wild look in his eye was less horrible than the anxious thirsting for deliverance, the never-ending torture of unrest!

The “never-ending torture of unrest” is the burden of existence we all carry, sloppily fumble, negotiate with an awkward grip and bent back. Büchner’s analysis fascinates in its refusal to lighten this burden or ponderously dwell on its existential weight. Instead, Lenz is a character study that the reader can’t quite get out of—we’re too inside the frame to see the full contours; precariously perched on Lenz’s shoulder, we have to jostle along with him, look through his wild eyes, gallop along with him on the energy of his madcap idea. The gallop is sad and beautiful and rewarding. Very highly recommended.

I shouldn’t be reading five novels at once. It’s a terrible idea, a symptom of a bad habit that I thought I’d broken, but after abandoning Levin’s tedious tome

I shouldn’t be reading five novels at once. It’s a terrible idea, a symptom of a bad habit that I thought I’d broken, but after abandoning Levin’s tedious tome  Iyer’s book dovetails nicely with W.G. Sebald’s first novel, Vertigo, which I picked up expressly to get the bad taste of Shteyngart out of my brain. Both books are haunted by Kafka, both blur the lines between fiction and biography, both are works of and about flânerie, and both are melancholy. The book comprises four sections; the first section tells the story of the romantic novelist Stendhal (or, more to the point, a version of Stendhal); the second section details two trips Sebald made to Italy, one in 1980, and one in 1987; the third

Iyer’s book dovetails nicely with W.G. Sebald’s first novel, Vertigo, which I picked up expressly to get the bad taste of Shteyngart out of my brain. Both books are haunted by Kafka, both blur the lines between fiction and biography, both are works of and about flânerie, and both are melancholy. The book comprises four sections; the first section tells the story of the romantic novelist Stendhal (or, more to the point, a version of Stendhal); the second section details two trips Sebald made to Italy, one in 1980, and one in 1987; the third  section, which I just read last night, describes a trip Kakfa took to Italy near the end of his life. I’m almost certain that I’ve read this section, “Dr. K Takes the Waters at Riva,” before — but I can’t remember where or when. It was strange reading it, almost as if I were experiencing some of the vertigo that permeates the volume. Full review forthcoming.

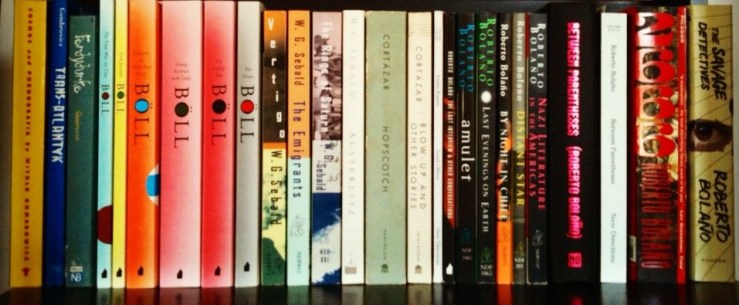

section, which I just read last night, describes a trip Kakfa took to Italy near the end of his life. I’m almost certain that I’ve read this section, “Dr. K Takes the Waters at Riva,” before — but I can’t remember where or when. It was strange reading it, almost as if I were experiencing some of the vertigo that permeates the volume. Full review forthcoming. Continuing in this Teutonic vein is Heinrich Böll’s novel The Clown (also Melville House). It’s postwar Germany, and Hans Schnier is a clown who’s crashing and burning. He hurts himself–purposefully–during a performance (at one of the increasingly more provincial venues he finds himself playing for these days) and retreats to Bonn, where he holes up in his small apartment and makes angry desperate phone calls (and tries not to drink too much brandy) and reflects on his past. What’s eating him up? His gal Marie, basically his common-law wife, has reverted back to her Catholic ways and up and left him for some chump named Zupfner. Schnier rants against a complacent and complicit German bourgeoisie, spitting vitriol against Protestants and Catholics alike; some of the best parts of the novel though are his ravings about art and the role of the “artiste” in society. Also: he can smell over the phone. Full review soon.

Continuing in this Teutonic vein is Heinrich Böll’s novel The Clown (also Melville House). It’s postwar Germany, and Hans Schnier is a clown who’s crashing and burning. He hurts himself–purposefully–during a performance (at one of the increasingly more provincial venues he finds himself playing for these days) and retreats to Bonn, where he holes up in his small apartment and makes angry desperate phone calls (and tries not to drink too much brandy) and reflects on his past. What’s eating him up? His gal Marie, basically his common-law wife, has reverted back to her Catholic ways and up and left him for some chump named Zupfner. Schnier rants against a complacent and complicit German bourgeoisie, spitting vitriol against Protestants and Catholics alike; some of the best parts of the novel though are his ravings about art and the role of the “artiste” in society. Also: he can smell over the phone. Full review soon. Wesley Stace’s new novel Charles Jessold, Considered as a Murderer (new from Picador) is a musical murder mystery set in the early part of 20th century Britain. Our (seemingly less than reliable) narrator Leslie Shepherd is a music critic with an aristocratic background who likes to spend his weekends collecting folk songs with other rich boys in the towns surrounding their country manors. He’s smitten (platonically, of course) with Charles Jessold, a middle class composer with a spark of avant-garde genius, and wins the younger man’s friendship quickly when he tells the story of Carlo Gesualdo, a fifteenth century composer/lord who kills his wife and her lover. (Notice the etymological connection between their names?) This tale of murder and cuckoldry is doubled in the ballad “

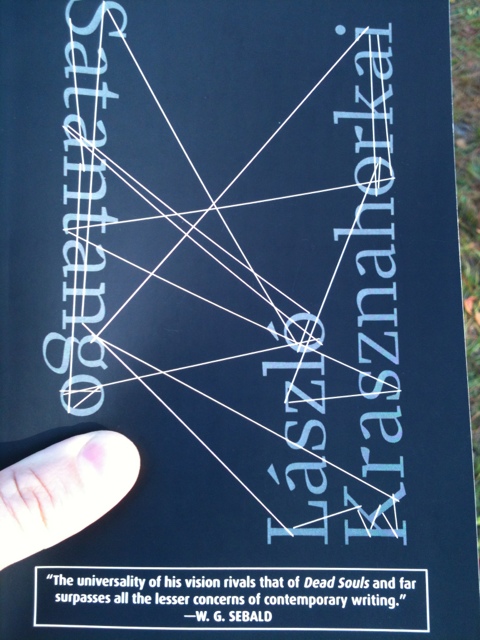

Wesley Stace’s new novel Charles Jessold, Considered as a Murderer (new from Picador) is a musical murder mystery set in the early part of 20th century Britain. Our (seemingly less than reliable) narrator Leslie Shepherd is a music critic with an aristocratic background who likes to spend his weekends collecting folk songs with other rich boys in the towns surrounding their country manors. He’s smitten (platonically, of course) with Charles Jessold, a middle class composer with a spark of avant-garde genius, and wins the younger man’s friendship quickly when he tells the story of Carlo Gesualdo, a fifteenth century composer/lord who kills his wife and her lover. (Notice the etymological connection between their names?) This tale of murder and cuckoldry is doubled in the ballad “ In W.G. Sebald: Image, Archive, Modernity, J.J. Long posits that the work of the late German author W.G. Sebald is best understood as the struggle for autonomous subjectivity in a world conditioned by the power structures of modernity. If the term “power structures” wasn’t a big enough tip-off, yes, Long’s analysis of Sebald is largely Foucauldian, and although he cites Foucault more than any other theorist (Freud is a distant second), the book is not a dogged attempt to make Sebald’s prose stick to Foucault’s theories. Rather, Long uses Foucault’s techniques to better understand Sebald’s works. As such, Long examines the ways that modernity affects power on the human body in Sebald’s work, tracing his protagonists’ encounters with modern institutions that exert power via archive and image.

In W.G. Sebald: Image, Archive, Modernity, J.J. Long posits that the work of the late German author W.G. Sebald is best understood as the struggle for autonomous subjectivity in a world conditioned by the power structures of modernity. If the term “power structures” wasn’t a big enough tip-off, yes, Long’s analysis of Sebald is largely Foucauldian, and although he cites Foucault more than any other theorist (Freud is a distant second), the book is not a dogged attempt to make Sebald’s prose stick to Foucault’s theories. Rather, Long uses Foucault’s techniques to better understand Sebald’s works. As such, Long examines the ways that modernity affects power on the human body in Sebald’s work, tracing his protagonists’ encounters with modern institutions that exert power via archive and image. Long’s study of Sebald is very much a description of modernity; in particular, of modernity as a series of affects of power and discipline upon the subject (again, very Foucauldian). It’s not particularly surprising then that Long, after locating so many Sebaldian traumas in the 19th and early 20th centuries, asserts that Sebald is a modernist and not a postmodernist. He bases this claim not on the formal elements of Sebald’s prose, which he readily concedes can just as easily be read as postmodernist, but rather on the way his “texts respond to the specific historical constellation” of modernity. Long continues–

Long’s study of Sebald is very much a description of modernity; in particular, of modernity as a series of affects of power and discipline upon the subject (again, very Foucauldian). It’s not particularly surprising then that Long, after locating so many Sebaldian traumas in the 19th and early 20th centuries, asserts that Sebald is a modernist and not a postmodernist. He bases this claim not on the formal elements of Sebald’s prose, which he readily concedes can just as easily be read as postmodernist, but rather on the way his “texts respond to the specific historical constellation” of modernity. Long continues–