Brazilian writer João Gilberto Noll’s 1991 novella Quiet Creature on the Corner is new in English translation (by Adam Morris) from Two Lines Press.

The book is probably best read without any kind of foregrounding or forewarning.

Forewarning (and enthusiastic endorsement): Quiet Creature on the Corner is a nightmarish, abject, kinetic, surreal, picaresque read, a mysterious prose-poem that resists allegorical interpretation. I read it and then I read it again. It’s a puzzle. I enjoyed it tremendously.

So…what’s it about?

For summary, I’ll lazily cite the back of the book:

…Quiet Creature on the Corner throws us into a strange world without rational cause and effect, where everyone always seems to lack just a few necessary facts. The narrator is an unemployed poet who is thrown in jail after inexplicably raping his neighbor. But then he’s abruptly taken to a countryside manor where all that’s required of him is to write poetry. What do his captors really want from him?

There’s a lot more going on than that.

So…what’s it about? What’s the “a lot more”?

Okay then.

Maybe let’s use body metaphors. Maybe that will work here.

We are constantly leaking. Blood, sweat, tears. Piss, shit, decay. Cells sloughing off. Snot trickling. Vomit spewing. Shuffling of this mortal etc.

(—Are we off to a bad start? Have I alienated you, reader, from my request that you read Noll’s novella?—)

What I want to say is:

We are abject: there are parts of us that are not us but are us, parts that we would disallow, discard, flush away. We are discontinuous, rotten affairs. Bodies are porous. We leak.

We plug up the leaks with metaphors, symbols, tricks, gambits, recollections, reminiscences. We convert shame into ritual and ritual into history. We give ourselves a story, a continuity. An out from all that abjection. An organization to all those organs. We call it an identity, we frame it in memory.

What has this to do with Noll’s novella?, you may ask, gentle reader. Well. We expect a narrative to be organized, to represent a body of work. And Quiet Creature on the Corner is organized, it is a body—but one in which much of the connective tissue has been extricated from the viscera.

We never come to understand our first-person narrator, a would-be poet in the midst of a Kafkaesque anti-quest. And our narrator never comes to understand himself (thank goodness). He’s missing the connective tissue, the causes for all the effects. Quiet Corner exposes identity as an abject thing, porous, fractured, unprotected by stabilizing memory. What’s left is the body, a violent mass of leaking gases liquids solids, shuttling its messy consciousness from one damn place to the next.

Perhaps as a way to become more than just a body, to stabilize his identity, and to transcend his poverty, the narrator writes poems. However, apart from occasional brusque summaries, we don’t get much of his poetry. (The previous sentence is untrue. The entirety of Quiet Creature on the Corner is the narrator’s poem. But let’s move on). He shares only a few lines of what he claims is the last poem he ever writes: “A shot in the yard out front / A hardened fingernail scraping the tepid earth.” Perhaps Quiet Creature is condensed in these two lines: A violent, mysterious milieu and the artist who wishes to record, describe, and analyze it—yet, lacking the necessary tools, he resorts to implementing a finger for a crude pencil. Marks in the dirt. An abject effort. A way of saying, “I was here.” A way of saying I.

Poetry perhaps offers our narrator—and the perhaps here is a big perhaps—a temporary transcendence from the nightmarish (un)reality of his environs. In an early episode, he’s taken from jail to a clinic where he is given a nice clean bed and decides to sleep, finally:

I dreamed I was writing a poem in which two horses were whinnying. When I woke up, there they were, still whinnying, only this time outside the poem, a few steps a way, and I could mount them if I wanted to.

Rest, dream, create. Our hero moves from a Porto Alegre slum to a hellish jail to a quiet clinic and into a dream, which he converts into a pastoral semi-paradise. The narrator lives a full second life here with his horses, his farm, a wife and kids. (He even enjoys a roll in the hay). And yet sinister vibes reverberate under every line, puncturing the narrator’s bucolic reverie. Our poet doesn’t so much wake up from his dream; rather, he’s pulled from it into yet another nightmare by a man named Kurt.

Kurt and his wife Gerda are the so-called “captors” of the poet, who is happy, or happyish, in his clean, catered captivity. He’s able to write and read, and if the country manor is a sinister, bizarre place, he fits right in. Kurt and Gerda become strange parent figures to the poet. Various Oedipal dramas play out—always with the connective tissue removed and disposed of, the causes absent from their effects. We get illnesses, rapes, corpses. We get the specter of Brazil’s taboo past—are Germans Kurt and Gerda Nazis émigrés? Quiet Creature evokes allegorical contours only to collapse them a few images later.

What inheres is the novella’s nightmare tone and rhythm, its picaresque energy, its tingling dread. Our poet-hero finds himself in every sort of awful predicament, yet he often revels in it. If he’s not equipped with a memory, he’s also unencumbered by one.

And without memory the body must do its best. A representative passage from the book’s midway point:

Suddenly my body calmed, normalizing my breathing. I didn’t understand what I was doing there, lying with my head in a puddle of piss, deeply inhaling the sharp smell of the piss, as though, predicting this would help me recover my memory, and the memory that had knocked me to the floor appeared, little by little, and I became fascinated, as what had begun as a theatrical seizure to get rid of the guy who called himself a cop had become a thing that had really thrown me outside myself.

Here, we see the body as its own theater, with consciousness not a commander but a bewildered prisoner, abject, awakened into reality by a puddle of piss and threatened by external authorities, those who call themselves cops. Here, a theatrical seizure conveys meaning in a way that supersedes language.

Indeed our poet doesn’t harness and command language with purpose—rather, he emits it:

No, I repeated without knowing why. Sometimes a word slips out of me like that, before I have time to formalize an intention in my head. Sometimes on such occasions it comes to me with relief, as though I’ve felt myself distilling something that only once finished and outside me, I’ll be able to know.

And so, if we are constantly leaking, we leak language too.

It’s the language that propels Noll’s novella. Each sentence made me want to read the next sentence. Adam Morris’s translation rockets along, employing comma splice after comma splice. The run-on sentences rhetorically double the narrative’s lack of connecting tissue. Subordinating and coordinating conjunctions are rare here. Em dashes are not.

The imagery too compels the reader (this reader, I mean)—strange, surreal. Another passage:

Our arrival at the manor.

The power was out. We lit lanterns.

I found a horrible bug underneath the stove. It could have been a spider but it looked more like a hangman. I was on my knees and I smashed it with the base of my lantern. The moon was full. The low sky, clotted with stars, was coming in the kitchen window. December, but the night couldn’t be called warm—because it was windy. I was crawling along the kitchen tiles with lantern in hand, looking for something that Kurt couldn’t find. I was crawling across the kitchen without much hope for my search: he didn’t the faintest idea of where I could find it.

What was the thing Kurt and the narrator searched for? I never found it, but maybe it’s somewhere there in the narrative.

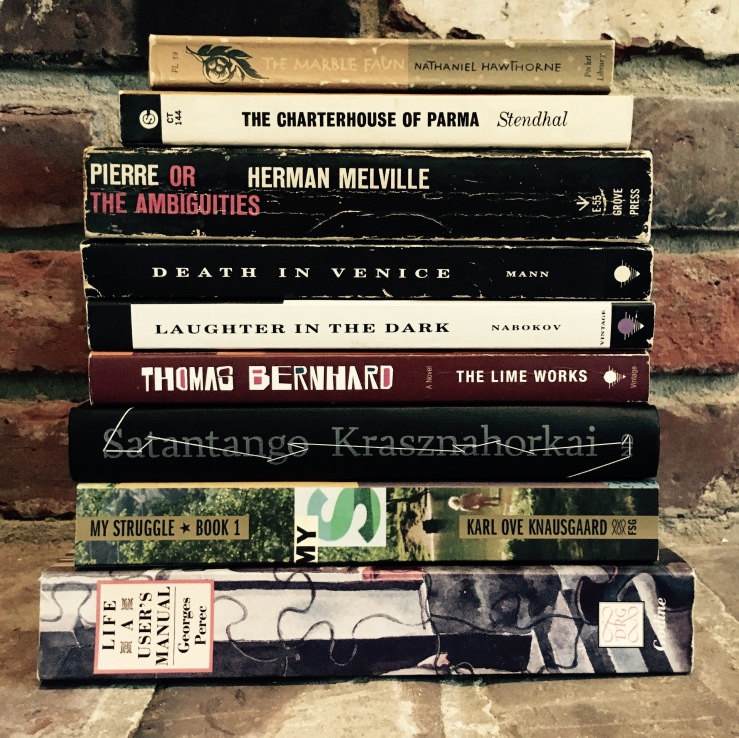

Quiet Creature on the Corner is like a puzzle, but a puzzle without a reference picture, a puzzle with pieces missing. The publishers have compared the novella to the films of David Lynch, and the connection is not inaccurate. Too, Quiet Creature evokes other sinister Lynchian puzzlers, like Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 (or Nazi Literature in the Americas, which it is perhaps a twin text to). It’s easy to compare much of postmodern literature to Kafka, but Quiet Creature is truly Kafkaesque. It also recalled to me another Kafkaesque novel, Alasdair Gray’s Lanark—both are soaked in a dark dream logic. Other reference points abound—the paintings of Francis Bacon, Leon Golub, Hieronymus Bosch, Goya’s etchings, etc. But Noll’s narrative is its own thing, wholly.

I reach the end of this “review” and realize there are so many little details I left out that I should have talked about–a doppelgänger and street preachers, an election and umbanda, Bach and flatulence, milking and mothers…the wonderful crunch of the title in its English translation—read it out loud! Also, as I reach the end of this (leaky) review, I realize that I seem to understand Quiet Creature less than I did before writing about it. Always a good sign.

João Gilberto Noll’s Quiet Creature on the Corner isn’t for everyone, but I loved it, and look forward to future English translations—Two Lines plans to publish his 1989 novel Atlantic Hotel in the spring of next year. I’ll probably read Quiet Creature again before then. Hopefully I’ll find it even weirder.