Denis Johnson’s story “Strangler Bob” is the third selection in The Largesse of the Sea Maiden. At about 20 pages, it’s also the shortest piece in the collection (the other four stories run between 40 and 50 pages). While still a bit longer than the stories in Johnson’s seminal collection Jesus’ Son, “Strangler Bob” nevertheless seems to pulse from that same vein, its narrator Dink another iteration of Jesus’ Son’s Fuckhead. Indeed, “Strangler Bob” feels a bit like an old sketch that’s been reworked by Johnson into something that fits thematically into Largesse.

Here’s the opening paragraph of “Strangler Bob” in full, which gives us the basic premise and setting (and you can’t beat those two opening sentences):

You hop into a car, race off in no particular direction, and blam, hit a power pole. Then it’s off to jail. I remember a monstrous tangle of arms and legs and fists, with me at the bottom gouging at eyes and doing my utmost to mangle throats, but I arrived at the facility without a scratch or a bruise. I must have been easy to subdue. The following Monday I pled guilty to disturbing the peace and malicious mischief, reduced from felony vehicular theft and resisting arrest because—well, because all this occurs on another planet, the planet of Thanksgiving, 1967. I was eighteen and hadn’t been in too much trouble. I was sentenced to forty-one days.

Those forty-one days take us from Thanksgiving to the New Year, with the story’s spiritual climax occurring on Christmas Eve.

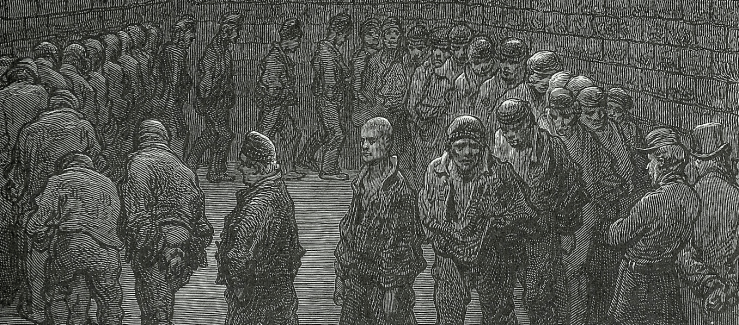

Before we get to that climax Johnson builds an unexpectedly rich world in the county lockup, populating it with young toughs who can’t yet see how bad the paths they’ve chosen will be. The men of Johnson’s jail aren’t simply down on their luck or somehow morally misunderstood. They are jovial young fuck-ups who plan to continue fucking up their lives the minute they get out.

A lot of the stage-setting and background characterization in “Strangler Bob” reads like picaresque sketches that Johnson had lying about unused from decades ago. Much of the early part of the story is dedicated to “the blond sociopathic giant Jocko,” a sort of prince of the jail who saves a crazy kid from being murdered by the other inmates. Such scenes give the story a ballast of baroque energy and even an unexpectedly-comic realism, but they don’t fully fit into the main theme of the story, which is hunger.

On his first day in the jail the narrator Dink is warned not to oversleep or he will have his breakfast stolen. Hardheaded, he sleeps in anyway, but learns from his mistake:

After that I had no trouble rousing myself for the first meal, because other than the arrival of food we had nothing in our lives to look forward to, and the hunger we felt in that place was more ferocious than any infant’s. Corn flakes for breakfast. Lunch: baloney on white. For dinner, one of the canned creations of Chef Boyardee, or, on lucky days, Dinty Moore. The most wonderful meals I’ve ever tasted.

Hunger in “Strangler Bob” is an expression of the deep boredom the prisoners feel, and mealtimes become the only way these men measure the passing of time. The hunger in “Strangler Bob” is not just a desire for food, but rather something to fill up the void, the space, the empty feeling. In this world, romantic adventure is ironized into confined torpor:

Dundun, BD and I formed a congress and became the Three Musketeers—no hijinks or swashbuckling, just hour upon hour of pointless conversation, misshapen cigarettes, and lethargy.

Dundun and BD are perhaps unlikely friends for Dink—

Dundun was short and muscled, I was short and puny, and BD was the tallest man in the jail, with a thick body that tapered up toward freakishly narrow shoulders.

—but their fellowship holds together because they had “long hair and chased after any kind of intoxicating substance.” Thanks to BD they get their mitts on some LSD:

BD told us he had a little brother, still in high school, who sold psychedelic drugs to his classmates. This brother came to visit BD and left him a hotrod magazine, one page of which he’d soaked in what he told BD was psilocybin, but was likelier just, BD figured, LSD plus some sort of large-animal veterinary tranquilizer. In any case: BD was most generous. He tore the page from the magazine, divided it into thirds, and shared one third with me and one with Donald Dundun, offering us this shredded contraband as a surprise on Christmas Eve.

The ink from the newsprint turns their tongues black. Narrator Dink seems to think that the LSD was not evenly distributed on the page though—BD trips the hardest, seeing snow falling indoors, but Dink seems to think he’s mostly unaffected, while Dundun denies any effect at all. However, consider this exchange between Dink and Dundun, which suggests that they might be tripping harder than they think:

“I’m feeling all the way back to my roots. To the caves. To the apes.” He turned his head and looked at us. His face was dark, but his eyeballs gave out sparks. He seemed to be positioned at the portal, bathed in prehistoric memories. He was summoning the ancient trees—their foliage was growing out of the walls of our prison, writhing and shrugging, hemming us in.

A sloppy and unnecessary Freudian analysis of the three kids parcels them out easily as id (Dundun the apeman), super ego (BD the strange moralist), and ego, our narrator who rejects any kind of spirituality in a world where “Asian babies fried in napalm.”

Dink’s cellmate, the eponymous Strangler Bob, poses a challenge to the narrator’s easy nihilism though. Even though Dink believes that he’s not affected by the LSD, his encounter with Bob on Christmas Eve reads like a bad trip:

The only effect I felt seemed to coalesce around the presence of Strangler Bob, who laughed again—“Hah!”—and, when he had our attention, said, “It was nice, you know, it being just the two of us, me and the missus. We charcoaled a couple T-bone steaks and drank a bottle of imported Beaujolais red wine, and then I sort of killed her a little bit.”

To demonstrate, he wrapped his fingers around his own neck while we Musketeers studied him like something we’d come on in a magic forest.

Dundun then exclaims that Strangler Bob is “the man who ate his wife” — but Bob admonishes that his cannibalism was greatly exaggerated:

Strangler Bob said, “That was a false exaggeration. I did not eat my wife. What happened was, she kept a few chickens, and I ate one of those. I wrung my wife’s neck, then I wrung a chicken’s neck for my dinner, and then I boiled and ate the chicken.”

The hunger in Strangler Bob is perverse and abject; his crime is of a moral magnitude far more intense than the malicious hijinks the youthful Musketeers have perpetrated–it’s taboo, a challenge to all moral order. He’s also an oracle of strange dooms:

He said, “I have a message for you from God. Sooner or later, you’ll all three end up doing murder.” His finger materialized in front of him, pointing at each of us in turn—“Murderer. Murderer. Murderer”

We learn in the final melancholy paragraphs of the story that Bob’s prophecy comes true, more or less. In those paragraphs too there is a moment of grace, albeit a grace hard purchased. Of the latter part of his life, the Dink tells us:

I was constantly drunk, treated myself as a garbage can for pharmaceuticals, and within a few years lost everything and became a wino on the street, drifting from city to city, sleeping in missions, eating at giveaway programs.

It’s worth noting that if Dink were 18 in the fall of 1967, he would likely have been born in 1949, the year that Denis Johnson was born. The narrators of two other stories in Largesse are also born in or around 1949, and it’s my belief that all of the narrators are essentially the same age, and all are pseudoautofictional iterations of Johnson.

In “Strangler Bob,” Dink is an iteration that fails to thrive, that can’t survive addiction and recovery and enter into a new life. He does not heed Bob’s warning, and at the end of the story he laments that he is a poisoned person who has poisoned others:

When I die myself, B.D. and Dundun, the angels of the God I sneered at, will come to tally up my victims and tell me how many people I killed with my blood.

These final lines push the narrator into a place of bare remorse and regret, as he reflects back on his time in the jail, which he describes in retrospect as “some kind of intersection for souls.” Dink now sees that he’s failed to acknowledge the messengers that might have sent him on a better path. Angels come in strange forms.

Very early Christmas morning on the planet of 1967, after “the festival of horrors” that constituted the LSD trip, Strangler Bob gives one last message, a strange delivered in Dink’s grandmother’s voice:

I studied him surreptitiously over the edge of the bunk, and soon I could see alien features forming on the face below me, Martian mouth, Andromedan eyes, staring back at me with evil curiosity. It made me feel weightless and dizzy when the mouth spoke to me with the voice of my grandmother: “Right now,” Strangler Bob said, “you don’t get it. You’re too young.” My grandmother’s voice, the same aggrieved tone, the same sorrow and resignation.

“You’re too young” — wisdom is purchased through folly, pain, terrible mistakes, crimes and sins. The narrator’s grandmother ventriloquizes Strangler Bob, but she doesn’t have a moral message, just tired pain.

The voice here is Denis Johnson’s voice too, inhabiting a mad oracle, warning some version of himself that exists today.

You can read “Stranger Bob” online here.

I wrote about the title story in The Largesse of the Sea Maiden here.

I wrote about the second story, “The Starlight on Idaho” here.