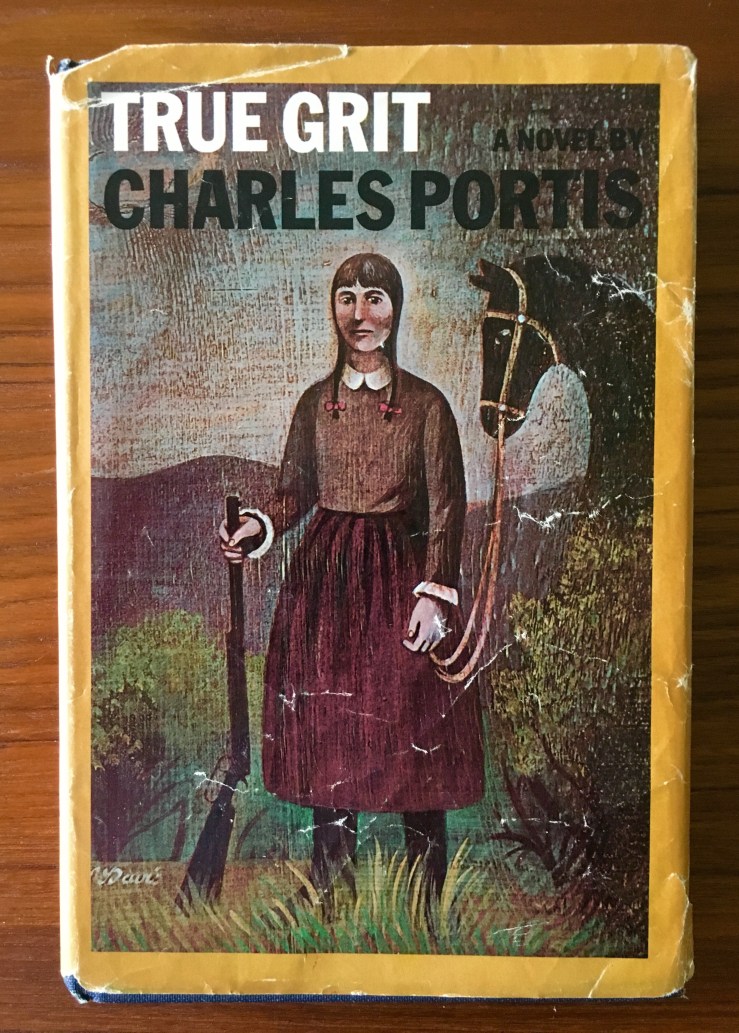

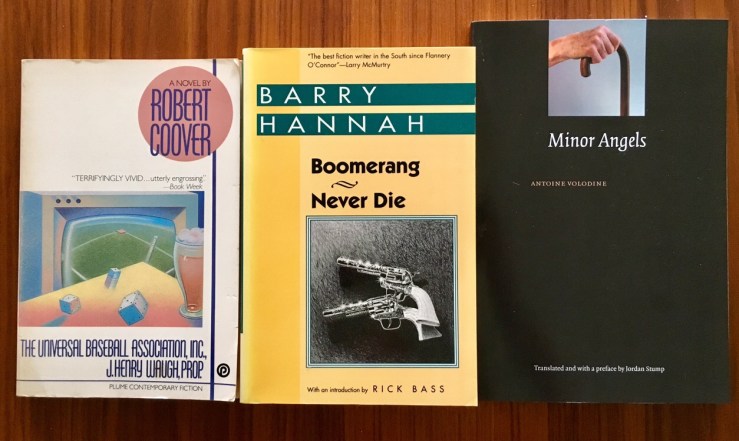

Antoine Volodine’s novel Radiant Terminus is a 500-page post-apocalyptic, post-modernist, post-exotic epic that destabilizes notions of life and death itself. Radiant Terminus is somehow simultaneously fat and bare, vibrant and etiolated, cunning and naive. The prose, in Jeffrey Zuckerman’s English translation, shifts from lucid, plain syntax to poetical flights of invention. Volodine’s novel is likely unlike anything you’ve read before—unless you’ve read Volodine.

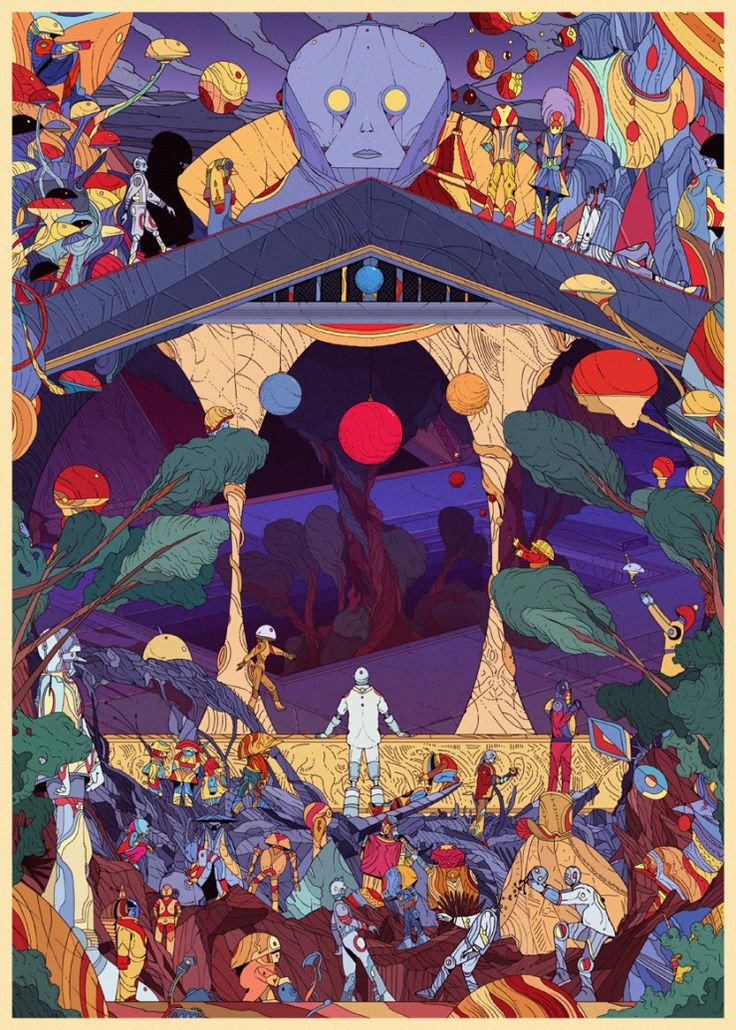

Radiant Terminus begins with its hero Kronauer fleeing into an irradiated wasteland. Kronauer and two of his comrades are escaping from the Orbise, the capital of the Second Soviet Union, which has been invaded by dog-headed fascists. World-wide Marxism-Leninism has fallen, and the stability of nuclear-powered self-sufficiency has collapsed into the apocalyptic promise of a “world that nuclear accidents had made unlivable for ten millennia to come.” The world is indeed increasingly unlivable, but it also has become, we will find, a place for the undying as well. “Hell is on the surface, it’s here,” one character flatly remarks, adding, “No need to dive into the core.”

But Kronauer will have to dive into the core, at least metaphorically. When one of his comrades, succumbing to radiation poison, can no longer move, Kronauer seeks help, crossing the steppe and bravely venturing into the dark forest. Born in the sanctity of the Orbise, Kronauer had been schooled to focus “on the future of Communes for workers and countrymen. His view of the world was illuminated by proletarian morality: self-sacrifice, altruism, and confrontation.” He is driven to save his comrade, but we know from the outset that hopes are slim.

What matters here is Kronauer’s essential idealism. By the end of the novel, Kronauer will suffer, wondering if he will eventually abandon the principles that underwrite his sense of self. He worries that he will eventually slip into a “total regression to primitive hunting, intelligence sidelined for instincts, and, especially, deep down, an irrepressible desire to kill, to slaughter, and to hurt, even if he couldn’t remember anymore what had brought about this nightmare.”

We enter Radiant Terminus in the midst of a nightmare that somehow only intensifies. Kronauer finds his way to what might be the prospect of aid for his comrade, the titular Radiant Terminus, a collective farm that is somehow self-sustaining despite the ever-present specter of irradiated death. Not only is Radiant Terminus out of sync with the physical reality of the post-apocalyptic world, its principles don’t fully square with the tenets of the Second Soviet Union that have guided Kronauer’s mindset:

Radiant Terminus functioned on ideological principles that didn’t match up to the collectivist norms of the Orbise, but, as far as the allocation of goods went, the end result was the same. Disdain for property was, as had been the case throughout the Second Soviet Union, commonplace in the Levanidovo. It was a place where the Party had been extinguished, where the Party no longer existed, but where the idea of reestablishing capitalism and the bourgeoisie hadn’t occurred to anyone, and besides it had to be asked just what this thing called capitalism would have looked like at Radiant Terminus, and what bourgeoisie could be called upon to oppress the working class…

We come to understand, elliptically enough, that Radiant Terminus’s apparent prosperity (or at least sustainability) is purchased in large part via sacrifices made to the village’s old nuclear reactor core, which has melted down and is kept locked away. The core is a kind of doorway to hell. The citizens of Radiant Terminus offer it gifts from the old world:

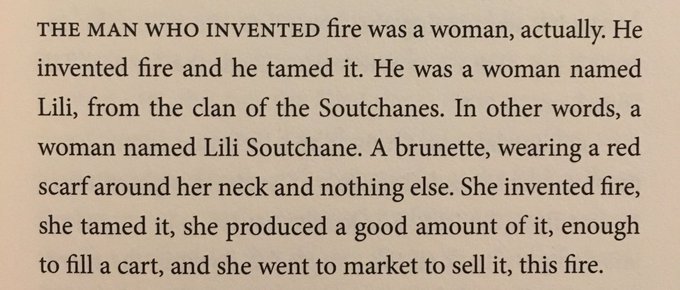

Every month, indeed, the core was fed. The heavy cover for the well was opened, and some of the bric-a-brac collected over the last season or two was knocked over the edge; just to show that people weren’t panicking and weren’t afraid of pathetic radionuclides. Tables and chairs, television sets, the tarry carcasses of cows and cowherds, tractor motors, charred schoolteachers who had been forgotten in their classrooms during the critical period, computers, remains of phosphorescent crows, moles, does, wolves, squirrels, clothes that looked perfect but had only to be shaken to set off a haze of sparks, inflated toothpaste tubes filled with constantly simmering toothpaste, albino dogs and cats, clusters of iron that continued to rumble with an inner fire, new combine harvesters that hadn’t yet been broken in and which gleamed at midnight as if they were lying in full sunlight, garden forks, hoes, axes, debarkers, accordions that spat out more gamma rays than folkloric melodies, pinewood planks that looked like ebony planks, Stakhanovites in their Sunday best with their hands mummified around their diplomas, forgotten when the event halls were evacuated. The ledgers with their pages turning day and night. Cash-register money, the copper coins clinking and shifting without anyone nearby. These were the sorts of things thrown into the void.

The Gramma Udgul was the one to handle the maneuver

We come to understand the Gramma Udgul as priestess-witch archetype; “condemned to immortality from her first interactions with nuclear reactor cores” she is both immune to the ravages of radiation and cursed by it. The Gramma Udgul has her counterpoint in Solovyei, the dominant antagonist of Radiant Terminus.

Solovyei is the “president” of Radiant Terminus, but his role is something closer to an archduke synthesized with an insane wizard. Like the Gramma Udgul, Solovyei is immortal (indeed, a century earlier, the pair were husband and wife). Solovyei rules greedily over Radiant Terminus, and warns Kronauer to stay away from his three daughters. He is an inverted King Lear; mad, yes, but also deeply capable and cunning. Solovyei seems to find metaphysical sustenance in trips to Radiant Terminus’s nuclear core, emerging from time spent there “sizzling and blackened, weighed down with radiation and opaque poems.”

The development of Solovyei as a controlling intelligence—and Kronauer’s ideological resistance to his monomania as well as his three daughters’ battle against his invasive will—forms the main plot, such as it is, of Radiant Terminus. Solovyei is the author of the “horrors and oneiric aberrations” that haunt the characters and landscape that he is both collapsing center and impossible margin of. “It was hard to determine whether he was a mutant bird, a gigantic sorcerer, or a rich farmer from Soviet or Tolstoyan times,” the narrator declares at one point.

“This necromancer of the steppes,” Kronauer calls Solovyei, and then goes on to try to find language for the metaphysical:

This awful kolkhoz matchmaker, this reviver of cadavers, this horrible shadow, this giant impervious to radiation, this shamanic authority from nowhere, this president of nothing, this vampire in the form of a kulak, this strange man sitting on a stool, this abuser, this dominating man, this sleazy man, this unsettling man, this nuclear-reactor creature, this godless and lordless hypnotizer, this manipulator…

One of the key plot points of Radiant Terminus is that Solovyei can literally resurrect the dead, but cannot reanimate them back to what we would understand as true life:

….we all became bodies inhabited by Solovyei. Who knows whether this magic muzhik hasn’t taken advantage of us being dead, and if we aren’t all puppets within a theater where the manager, the actors, and the audience are all one and the same person

Some of Volodine’s chapters seem to inhabit Solovyei’s consciousness, a space that’s somehow both murky and sharp, an intelligence feasting on the agencies of other human beings:

Our best marionettes, I say. Him or me, doesn’t matter. When he’s stuck I keep going. Zombies, deep shadows, devoted servants. The dead stuck forever in the Bardo. Dead come from the dead. Wives come from unknown mothers. Henchmen. Best puppets and best dolls.

Every character who survives in the pages of Radiant Terminus seems to be susceptible to Solovyei’s oneiric horrors. He is the dream police, the puppet master — “Who’s he?” a minor character asks. The answer: “We don’t know…But we do know that he does with us whatever he wants. We’re in his hell.”

Solovyei’s daughters are the most sympathetic of his vampiric victims. These women, forced into the same unasked-for immortality as their father, find themselves repeatedly invaded by Solovyei, who haunts their dreams and walks around in their minds. One daughter sees herself “a creature imagined, possessed, and brought to life by Solovyei. A daughter of Solovyei, a daughter for Solovyei. A female annex in Solovyei’s life: nothing more than that.” They initiate their own eruptions of opposition: violence, suicidal rejection. Writing.

Near the end of Radiant Terminus, the narrator describes the novels of Hannko Vogulian, Solovyei’s eldest daughter:

In effect, they depicted the same twilit suffering of everyone, a magical but hopeless ordinariness, organic and political deterioration, infinite yet unwished-for resistance to death, perennial uncertainty about reality, or a penal progression of thought, penal, wounded, and insane.

We have here an internal description of the novel Radiant Terminus itself. Indeed, Radiant Terminus is always self-describing and always self-deconstructing: “Everything is in the same place, as in some kind of book, if you want to go to the trouble of thinking about it. That’s the ambiguity of ubiquity and achronia,” the narrator muses. When the narrator throws out the sentence, “These are complete works for no audience,” it almost feels like an inside joke. And Volodine can’t resist metanarrative descriptions of his own so-called post-exotic project:

If a post-exotic writer had been present at the scene, he would have certainly described it according to the techniques of magical socialist realism, with flights of lyricism, drops of sweat, and the proletarian exaltation that were part of the genre. It would have been a propagandist epic with reflections on the individual’s endurance in service to the collective.

Volodine’s Radiant Terminus works in all these modes while simultaneously subverting them. The result is an astounding novel, a work that will haunt any reader willing to tune into its strange vibrations and haunted frequencies. Very highly recommended.