Evan Lavender-Smith is an American writer who has published two books, Avatar and From Old Notebooks.

I really really really like his anti-novel (or whatever you want to call it) From Old Notebooks, which has recently been reissued by the good people at Dzanc Books.

(Here is my review of FON). I still haven’t read Avatar.

Evan talked with me about his writing, his reading, and other stuff over a series of emails. He was generous in his answers and I very much enjoyed talking with him.

Evan lives in New Mexico with his wife, son, and daughter. He has a website. Read his books.

Biblioklept: Do you know that first editions of From Old Notebooks are going for like three hundred dollars on Amazon right now?

ELS: Here at the house I have a whole drawer full of them. That’s how I’m planning to pay for the kids’ college.

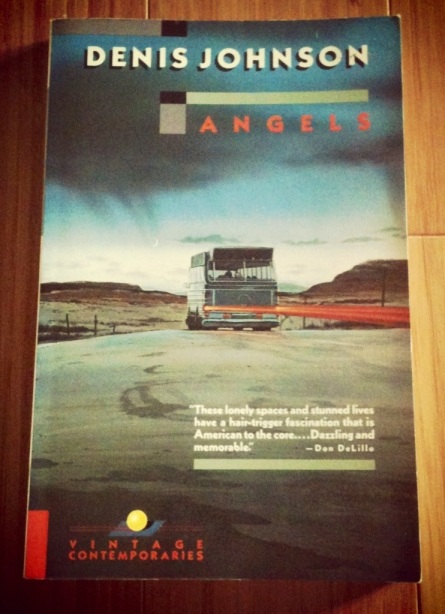

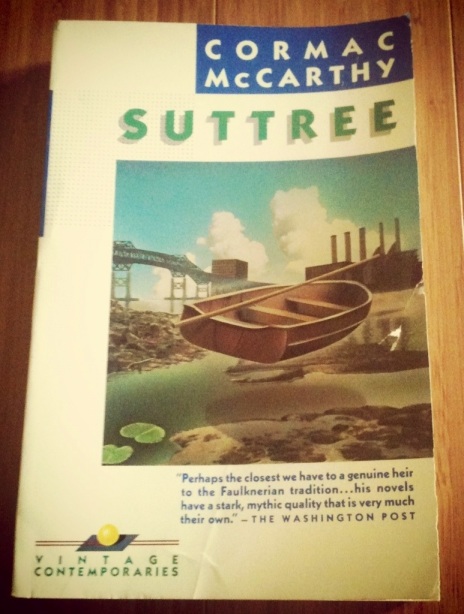

Biblioklept: I read that Cormac McCarthy won’t sign his books anymore because he has this reserve of signed editions that are for his son to sell and corner the market on. Or I think I read that.

Speaking of your kids: the parts in From Old Notebooks about them are some of my favorites, perhaps because the moments you describe seem so real to me, or that I relate so strongly to the feelings that you express. (My own kids, a daughter and son, are about the same age as your kids are in the book). Is it weird if I ask how your kids are?

ELS: Glad to hear some of that stuff resonates with you. No, I don’t think it’s weird. I believe the book even sort of self-consciously anticipates a certain reader’s empathetic engagement with it. There’s that passage somewhere, for example, in which we get something like an interview answer, something like “The real Evan Lavender-Smith has never made it past the first section of Ulysses, the real Evan Lavender-Smith has no children,” which I think maybe winks at the possibility of that type of readerly engagement. So no, it’s encouraging to hear that parts of the book seemed to work for you. My kids are great, by the way. Sofia’s at her violin lesson, Jackson’s doing an art project with his mom.

Biblioklept: The faux-interview answers crack me up. I think we’ve all done that in some way—that we go through these little experiments of interviewing ourselves, performing ourselves, imagining how others perceive us. You write your own obituary; at one point we get: ” ‘With my first book I hope to get all the cult of personality stuff out of the way’.” You remark that you don’t put dates on anything as “an act of defiance” against your “literary executors.” Moments like these seem simultaneously ironic and sincere.

I’m curious as to how closely you attended to these disjunctions—From Old Notebooks seems incredibly, I don’t know, organic.

ELS: At a certain point I became very aware that I was performing some version or versions of myself in the book, and I think the book tries to find ways of grappling with problems I perceived as bound up with that performance. One way was to insist on a narrative tone or mode somewhere in between irony and sincerity, or to regularly oscillate between or conflate these competing modes. Something like “I am the greatest writer in the history of the world!” might later be countered by “Gosh, my writing really blows, doesn’t it?”; or “My kids are so beautiful, I love them so much,” might be followed by “I wish those little fuckers were never born.” While the function of this variability is, in From Old Notebooks, probably mostly an apology or a mask for a kind of subjectivity I worry might come off as cliche and naive, that particular representation of the thinking subject — cleaved, inconsistent, heterogeneous — does strike me as truer of human experience and perception than the more streamlined consistency of expression and behavior we tend to associate with the conventional narratological device called “character.” When I try to look deep down inside myself, to really get a handle on my thinking, for example, or on my understanding of truth, I end up facing a real mess of disjunctive, contradictory forces competing for my attention. For me — and likely for the book, as well — the most immediate figure for this condition might be the confluence of sincerity and irony, the compossibility of taking a genuine life-affirming pleasure in, and exhibiting a kind of cynical hostility toward, the fact of my own existence.

Biblioklept: That contest between sincerity and irony seems present in many works of post-postmodern fiction. It’s clearly a conflict that marks a lot of David Foster Wallace’s stuff. You invoke Wallace a number of times in From Old Notebooks, but the style of the book seems in no way beholden to his books. Can you talk about his influence on you as a reader? A writer?

ELS: Wallace hugely influenced the way I think about any number of things. I think his most immediate influence on my writing is this blending of hieratic and demotic modes of language when I’m dealing with pretty much anything that requires the serious application of my writing mind; the hip nerdiness of his language was and still is very empowering to me. He made it seem super cool to geek out on books — “The library, and step on it,” says Hal in Infinite Jest — and back in high school and college that example was so vital for me, as someone entirely too obsessed with being both cool and well read. He served to guide my reading of other writers in a way that only John Barth and Brian Evenson have come close to matching; I poured over his essays for names, then went to the library and checked out and read all the books he mentioned, then reread his essays. His fiction’s most common subject matter — addiction, depression, the yearning for transcendence, the incommensurability of language and lived experience, problems of logic vis-a-vis emotion, metafiction’s values and inadequacies — all of this stuff hit very close to home. To my mind there’s little doubt that Infinite Jest is the best English-language novel published in the last 25 years. His advocacy for David Markson has got to be up there among the greatest literary rescue missions of the 20th century. In “Good Old Neon” he wrote what may be the most haunting long short story since “The Death of Ivan Ilych.” He galvanized young writers everywhere right when the internet was taking off and unwittingly served as a touchstone for emerging online literary communities that thrive today. I think for a lot of young writers, myself included, he was, maybe next to the emergence of the internet, the most important force in the language’s recent history. The list goes on and on. And also he helped me out personally, providing encouragement and advice that was so generous and inspiring. I was extremely troubled by his suicide and wasn’t able to write much or think about much else for quite a while.

With all that said, there are some things he says that bother me a bit. The synthesis of art and entertainment he espouses as it pertains to the role of the writer in the age of television — which I think in many ways corresponds to his striving for a new aesthetic in which the cerebral effects associated with 60s and 70s postmodernist fiction are complemented by or synthesized with the more visceral effects associated with 70s and 80s realist fiction — strikes me now as existing very much in opposition to what I believe in most passionately about writing: that it can and in the most important cases should exist in a state of absolute opposition to our entertainments. I’ve come to better appreciate, years after reading Wallace, the writing of people like Woolf and Beckett and Gaddis, those writers who are uncompromising in their vision of narrative art’s most radical and affecting possibilities and who necessarily, I believe, pay very little attention to any sort of entertainment imperative. The books I love most make me feel things strongly, and think things strongly, but rarely do they entertain me. If I want to be entertained, I know exactly where to go: a room without books. I’ve come to think of certain books as my life’s only source of intellectual solace; when I’m not despairing over the futility of everything under the sun, that unflagging commitment to a truly rigorous and uncompromising art that I perceive in a writer like Beckett seems to me a matter of life and death, just as serious as life can ever get. When Wallace talks that shit about art and entertainment, or about the need to add more heart or greater complexity of character to Pynchon or whatever, it makes me feel like I want to throw up. I heard him say once in an interview that he felt he couldn’t write the unfiltered stuff in his head, that it would be too radical or something, and the admission really upset me; it felt like in some serious way he had allowed his projection of an imaginary target audience’s desire to determine the form of his writing. I often feel something similar in the essays; I find many of them to be merely entertaining. I suppose I often judge the essays in relation to the fictions, which I find far superior in their attempt to overcome the strictures and conventions of language and form. Wallace was always at his best, to my reading, when he was really bearing down — when he was at his most difficult.

But no doubt he’s been monumentally important to me, more so than any other recent fiction writer, and in more ways than I can name. There’s something in From Old Notebooks where the methodical awkwardness and wordiness of so many of his sentences is likened to the affectation of bumping up against the limits of language. That’s probably what I take away from him more than anything: when I sit down at the laptop to face the language, I often feel myself struggling with the words as well as struggling to demonstrate that I’m struggling with the words. That’s pure Wallace: word-by-word, letter-by-letter self-consciousness. (There’s another thing in From Old Notebooks about how I’m always talking shit because I care for him so deeply … which is why the paragraph before this one). Continue reading “An Interview with Evan Lavender-Smith” →