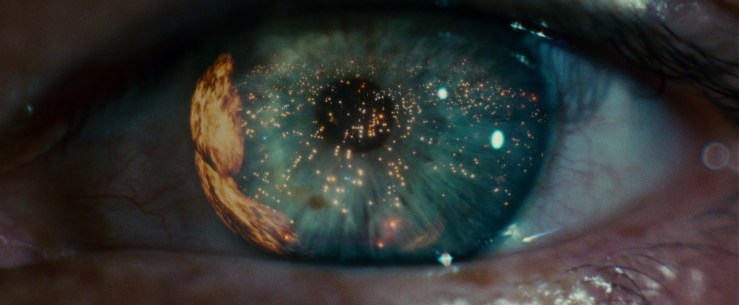

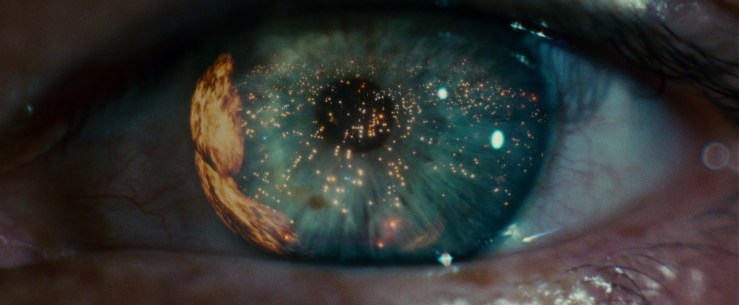

From Blade Runner, 1982. Directed by Ridley Scott with cinematography by Jordan Cronenweth. Via Screen Musings.

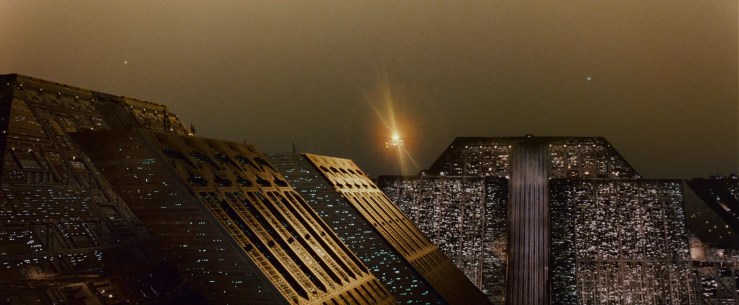

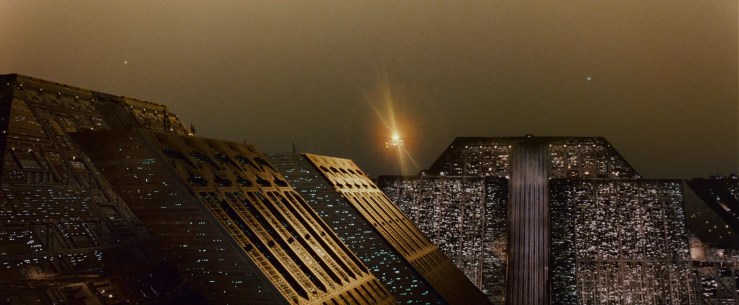

From Blade Runner, 1982. Directed by Ridley Scott with cinematography by Jordan Cronenweth. Via Screen Musings.

This strange and impressionistic paraphrase of Ridley Scott’s 1982 film Blade Runner is by Anders Ramsell, who painted all 12,597 frames using only water colors. The edit features dialogue and music from the film and the radical compression of the plot—edited down to just over half an hour—gives this painted film a dreamy, surreal texture. (Via Boing Boing, which I’m sure all you hepcats follow anyway, but this film is too lovely not to share again, in case, y’know, you didn’t already see it somehow).

The New Yorker has published an excerpt of Cormac McCarthy’s script for The Counselor, a film directed by Ridley Scott that will come out this fall.

An excerpt of the excerpt:

the kid rakes an object from under the paper into his helmet and puts down the paper and stands and puts the helmet under his arm and crosses the plaza to his bike and puts his foot over the bike and starts it and pulls his gloves from the helmet and lays them on the tank in front of him and pulls on the helmet and fastens the strap and then pulls on the gloves and kicks back the stand and pulls away into the traffic.

night. two-lane blacktop road through the high desert. A car passes and the lights recede down the long straight and fade out. A man walks out from the scrub cedars that line the road and stands in the middle of the road and lights a cigarette. He is carrying a roll of thin braided wire over one shoulder. He continues across the road to the fence. A tall metal pipe is mounted to one of the fence posts and at the top—some twenty feet off the ground—is a floodlight. The man pushes the button on a small plastic sending unit and the light comes on, flooding the road and the man’s face. He turns it off and walks down the fence line a good hundred yards to the corner of the fence and here he drops the coil of wire to the ground and takes a flashlight from his back pocket and puts it in his teeth and takes a pair of leather gloves from his belt and puts them on. Then he loops the wire around the corner post and pulls the end of the wire through the loop and wraps it about six times around the wire itself and tucks the end several times inside the loop and then takes the wire in both hands and hauls it as tight as he can get it. Then he takes the coil of wire and crosses the road, letting out the wire behind him. In the cedars on the far side, a flatbed truck is parked with the bed of the truck facing the road. There is an iron pipe at the right rear of the truck bed mounted vertically in a pair of collars so that it can slide up and down and the man threads the wire through a hole in the pipe and pulls it taut and stops it from sliding back by clamping the wire with a pair of vise grips. Then he walks back out to the road and takes a tape measure from his belt and measures the height of the wire from the road surface. He goes back to the truck and lowers the iron pipe in its collars and clamps it in place again with a threaded lever that he turns by hand against the vertical rod. He goes out to the road and measures the wire again and comes back and wraps the end of the wire through a heavy three-inch iron ring and walks to the front of the truck, where he pulls the wire taut and wraps it around itself to secure the ring at the end of the wire and then pulls the ring over a hook mounted in the side rail of the truck bed. He stands looking at it. He strums the wire with his fingers. It gives off a deep resonant note. He unhooks the ring and walks the wire to the rear of the truck until it lies slack on the ground and in the road. He lays the ring on the truck bed and goes around and takes a walkie-talkie from a work bag in the cab of the truck and stands in the open door of the truck, listening. He checks his watch by the dome light in the cab.

RIP Tony Scott, 1944-2012

British filmmaker Tony Scott committed suicide by jumping off of a bridge in San Pedro, California yesterday. He was 68.

Scott’s films were rarely critical favorites, although they were generally big hits. Scott’s films share, for the most part, a frenetic energy and a highly stylized visual flair.

His biggest hit was probably Top Gun, although he was also the man responsible for Beverly Hills Cop 2, Enemy of the State, Days of Thunder, The Last Boy Scout, and Crimson Tide.

My favorite Tony Scott film is True Romance, which I sneaked into a theater to see in ninth grade, and which changed my life to a small degree. Quentin Tarantino penned True Romance, and I think Scott was at his best with an offbeat writer, as when he worked with Richard Kelly on the very weird and unfairly maligned film Domino, which I’ve always loved.

Tony Scott is brother to Ridley Scott. For years I’ve had a game with a friend about the two, a game where I stick up for Tony, insist Tony is the real talent in the Scott family.

His suicide makes me unduly sad.

A list of great sci-fi movies would undoubtedly include Ridley Scott’s signature films, Alien (1979) and Blade Runner (1982), but I don’t know if there’s enough room on that list for Scott’s latest Prometheus, a gorgeous collection of set-pieces smeared onto a messy, hole-filled plot, signifying nothing. I’ve already written at some length about Prometheus’s metaphysical shortcomings, but I’m never especially happy to write negative reviews without providing alternatives. Here are seven movies that demonstrate the best in depth of intellect that the genre has to offer.

1. Metropolis, 1927 (Dir. Fritz Lang)

Metropolis foregrounds many of the tropes that will come to dominate serious sci-fi (film and literature alike). The dystopian future of Metropolis imposes a strict division of classes, relegating the poor workers to underground drudgery while the (literal) upper class enjoy privileged leisure. Lang explores this divide via a Romeo & Juliet story of sorts—Freder, son of the city’s Master becomes infatuated with Maria, a girl from the underworld. He follows her into the labyrinth under the city and soon witnesses industrial horrors that harm the subterranean workers. The plot becomes more complicated when a mad scientist unveils an automaton—a robotic Maria—that he will use as part of a nefarious scheme. Metropolis’s expressionistic design and camera work still seem fresh and innovative almost a century after filming, and the film’s take on class disparity is as affecting as ever.

2. Alphaville, 1965 (Dir. Jean-Luc Godard)

Godard’s dystopian New Wave crime noir talkie follows the strange exploits of Lemmy Caution, who drives in from the Outlands in his Ford Galaxie to find a missing agent, capture the founder of Alphaville, and destroy Alpha 60, the totalitarian computer that keeps Alphaville’s citizens from indulging in poetry (or other forms of free expression). Godard makes no attempt to design a future: Alphaville is filmed in contemporary Paris. The effect is baffling; Alphaville is an exercise in uncanny realizations. The dialogue is pure New Wave stuff—crammed with literary and art reference—and will just as likely bore as many audience members as it enthralls. In the end though, Anna Karina as Natacha von Braun is reason enough to watch this film.

3. 2001: A Space Odyssey,1968 (Dir. Stanley Kubrick).

Watch it. Then watch it again.

4. Solaris, 1972 (Dir. Andrei Tarkovsky)

Tarkovsky’s Solaris is a slow, engrossing meditation on grief. Based on the novel by Polish writer Stanisław Lem, Solaris centers on psychologist Kris Kelvin, who goes to the space station orbiting the planet Solaris in order to investigate the series of emotional collapses that the crew have suffered. Kelvin soon slips into his own existential crisis, as a ghost–or psychological construct—of his dead wife appears to him. Solaris is gorgeous and measured, using its near-three-hour running time to grand effect.

5. The Thing, 1982 (Dir. John Carpenter)

Antarctic research station. Shapeshifting parasites. Kurt Russell. Dogs. Flamethrowers. Blood tests. Kurt Russell’s beard. Ennio Morricone’s score. Wilford Fucking Brimley. Paranoia. Paranoia. Paranoia.

6. Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, 1984 (Dir. Hayao Miyazaki)

A millennium after apocalyptic war destroys human civilizations, the groups that remain scramble to control the few resources left on the planet. A toxic jungle swarming with mutant insects—and dominated by the giant Ohmus—encroaches on the few bastions of clean soil that remain to humankind. Adventurous Princess Nausicaä though learns the secrets of the jungle—and also knows how to communicate with the Ohmus—only she has to navigate sides in the emerging war between rival kingdoms. Miyazaki’s film, based on his manga, is lush and detailed, a fully-realized world that is simultaneously frightening and beautiful. The film’s take on ecology is not so much preachy as it is prescient.

7. Primer, 2004 (Dir. Shane Carruth)

Primer was shot on a $7,000 budget, but it never looks or feels cheap. This story of four engineers who invent a time machine in a garage is decidedly unglamorous and consistently engaging; Carruth (who also wrote and stars in the film) throws the audience into the deep end, offering no exposition, let alone explication for the audience to latch onto. The film explores the bizarre moral implications—and possible side effects (and defects) of time travel.

Prometheus, a big summer popcorn flick is the latest from Ridley Scott, the visionary auteur who gave us Kingdom of Heaven, Body of Lies, Robin Hood, and G.I. Jane. Okay, forgive the sarcasm—Scott is also responsible for some fine films, including Blade Runner and Alien, which Prometheus is most decidedly a prequel to, despite the early incoherent maybe-it-is-maybe-it-isn’t buzz from the studio. I list some of Scott’s recent (and not-so-recent) films as a reminder of what many film fans might be happy to overlook: Ridley Scott may have a keen sense of style and a competent grasp on storytelling and emotion, but he’s essentially a hired gun who happens to make better-than-average genre flicks. Prometheus is another entry in his middling non-canon.

Obligatory plot summary (no spoilers):

At the end of the 21st century, two archaeologists find a series of apparent star maps at ancient sites. Positing these maps as an invitation from “Engineers” — clearly, an alien species who created human life (how they make this inductive leap is never made quite clear) — the archaeologists head to the outer limits of the universe in the spaceship Prometheus. Along for the ride are a host of expendables, a skeptical Captain Janek (Idris Elba), ice-queen/corporate rep Vickers (Charlize Theron), and David (Michael Fassbender), an android who has apparently mastered Proto-Indo-European, the language these alien astronauts presumably speak (again, why this should be is never explicated). The Prometheus’s crew follow the star maps to an Earth-like moon and land near a giant temple, where they discover the remains of the Engineers, as well as some vases filled with black ooze. Being reasonable folks, they break quarantine and bring samples back on the Prometheus (recall now how Ripley tries so hard to prevent Dallas from bringing Kane back aboard the Nostromo in Alien). All proverbial hell breaks loose, and Prometheus begins to rack up a predictable body count as it slowly settles on archaeologist Shaw (played by an excellent Noomi Rapace) as its heroine.

Along the way, Prometheus gloms clumsily on to questions about creation and origin, but these questions lack real depth. The filmmakers rely heavily on clichés, hackneyed dialogue, and overdetermined images to present their creation theme, and the effect is largely divorced from the visceral spirituality we might otherwise associate with such a grand subject. Fassbender’s android is perhaps the clearest symbol of creation, a robot boy with daddy issues. (David’s creator Weyland, portrayed by Guy Pearce, foots the bill for space exploration because, of course, he’s searching for immortality. Quick aside: Why in the fuck is Pearce, a man in his forties, cast as a dying elderly man?). While Fassbender does a marvelous job as David the android, his performance retreads familiar territory (nods to Data and HAL 9000). David’s motivations are never entirely clear, and while some may argue this makes for a more interesting film, the lack of clarity is ultimately part of the film’s deflections. In Prometheus, the refusal to telegraph clear meaning isn’t subtle ambiguity, it’s the mark of empty spectacle, of filmmakers who aren’t entirely sure if they have a thesis or not.

This isn’t to say that there aren’t some fantastic moments in Prometheus. The film is beautiful, the designs impeccable, and Noomi Rapace’s Shaw emerges as an enthralling heroine, a final girl to rival Ripley. The film is at its finest when it focuses its energies on Shaw, as in a bizarre alien-abortion scene, probably the most thrilling segment of Prometheus. However, most of the marginal plots fail to coalesce. Charlize Theron’s Vickers could just as easily have been written out of the film, for example. Also, we’re told at the beginning that there are 17 crew members on Prometheus, but the body count here is so nebulous that it becomes impossible to keep track of who’s dead and who’s alive, let alone care. Ultimately, it’s the mishmash of mythologies that muddies Prometheus: Is this Pandora’s Box? Pinocchio? The Fountain of Youth? Genesis? The Book of Revelation?

Prometheus is all contours and surfaces, roomy, spacious, and slick. Near the end of the film, when one character, dying, announces “There is nothing . . .” it feels like a fairly concise summary of the film’s spiritual program. I suppose I’ve devoted so many words to Prometheus simply because I fear that it’s one of those popcorn flicks like Avatar or Inception that people will try to pretend are deep or meaningful or clever. In his glowing review, Roger Ebert suggests Prometheus is “all the more intriguing because it raises questions about the origin of human life and doesn’t have the answers.” Ebert’s analysis fails to leave out that the film doesn’t even try to answer—at best, it offers a smug shrug, a winking nihilism, pure cinematic spectacle as a substitution for meaning, gussied up in the robes of inquiry.

There is a moment though when Prometheus manages to synthesize its elegant bombast with the existential questions it wishes to pose. The end of the movie—yes, there are potential spoilers ahead—follows the same curve of self-annihilation that we see in Alien, with Ripley, final girl, safe but traumatized, a survivor who may now bear witness. In what I take to be the grandest shot in the film, a terrified Shaw gazes up at the alien spacecraft as it crashes down. The spacecraft recalls an ouroboros, the snake that eats its own tail, symbol of self-reflexivity, death-in-birth: it recalls too, both thematically and physically, the shapes of the reptilian aliens that haunt the rest of the Alien franchise. Watching the wreckage of ships, I was instantly reminded of the final chapter of Moby-Dick. In the epilogue, Ishamael tells us, “The Drama’s Done. Why then here does any one step forth? – Because one did survive the wreck.” The chapter begins with a quote from Job: “And I only am escaped alone to tell thee.” Whether or not Prometheus is actively alluding to Moby-Dick is beside the point. What both narratives do well is explore the capacity for survival, illustrating what it means to witness catastrophe on a cataclysmic scale. While Prometheus hardly explores its metaphysical questions with the depth or aplomb of Melville, it does tap into the same impulse that makes Alien such a great film, illustrating the Darwinian competition that underwrites existence.

If it seems I’ve been too hard on Prometheus, it was not my intention to declare it a bad or stupid or graceless film—again, it’s a good summer popcorn flick, filled with spectacle and thrills. I should point out that my wife and I caught the matinée, had a nice dinner, and then came home and watched Alien. Prometheus actually does a remarkable job of answering to some of the mysterious imagery that dominates the planetoid scenes in that film, but it ultimately suffers by comparison with Alien. Prometheus is too antiseptic and spacious, with none of the gritty, grimy, cramped corners that makes Scott’s earlier film so scary and paranoia-inducing. Prometheus also lacks the naturalistic performances and dialogue of Alien, which I suppose is more an issue of how much film has changed since the 1970s than anything else. On the whole though, Prometheus isn’t a bad summer flick—it just can’t live up to its marketing buzz, let alone its own metaphysical posturing.