Mahendra Singh is an author, illustrator and editor in Montreal. His other published books include a graphic novel version of The Hunting of the Snark, illustrations for D.A. Powell’s Cocktails, BSFA-award winner Adam Roberts’s 20 Trillion Leagues Under the Sea and Martin Olson’s NYT-best selling Adventure Time Encyclopaedia. American Candide is his first novel—read my review of it here. He was kind enough to talk with me about American Candide over a series of emails.

Biblioklept: How long have you been working on American Candide? When did you get the germ for the book?

Mahendra Singh: The Iraq War and its brazen marketing campaign got me started on American Candide. Not just the war but the hopelessness of opposing it made me realize how lightly the Enlightenment sits upon modern America. The way that people insisted upon being told what to think, it was torn from 18th-century headlines. Also, the ease with which religion fit into the war’s marketing scheme, almost like it was made for that … It’s not just the USA, of course, this is human nature throughout the world but since modern America is the equivalent of the Ancien Regime in so many ways, a riposte from the Enlightenment seemed indicated.

I had always wanted to update a classic that is only a classic because it no longer stings. Voltaire’s attacks on god, the military, imperialism and money don’t make many people squirm anymore. I wanted genuine squirm … I wanted younger readers to realize that we read the classics not because of dead white guys or because everybody-says-so but because the classics show us how little human nature changes. And once you realize that things were just as weird in the 18th-century, then you are embarked on the path of genuine free-thinking. It worked for some of the Founding Fathers so it’s actually double-plus-more patriotic than being clueless-and-proud-of-it.

I started working seriously on American Candide around the time of Hurricane Katrina (which could have been a 21st-century Lisbon Earthquake if it had happened to Boston) and the book’s first draft was done in about 3 months. I wanted to match Voltaire’s MO as best as possible:

1. Same word count

2. As close to the original plot as possible

3. Easy to read with no stylistic stuff to impede the story. Voltaire knew people don’t want to be preached to, they want to laugh and then you slip them the mickey. Hence the book can be read in three sessions (toilet, subway, opium den), I really did plan that.

After the first draft, it took several years to finish because I also freelance as an illustrator. Unlike Voltaire, I don’t live off the stock market.

Biblioklept: Was there a particular translation of Candide that you worked from or favored? Or did you read it in French, perhaps?

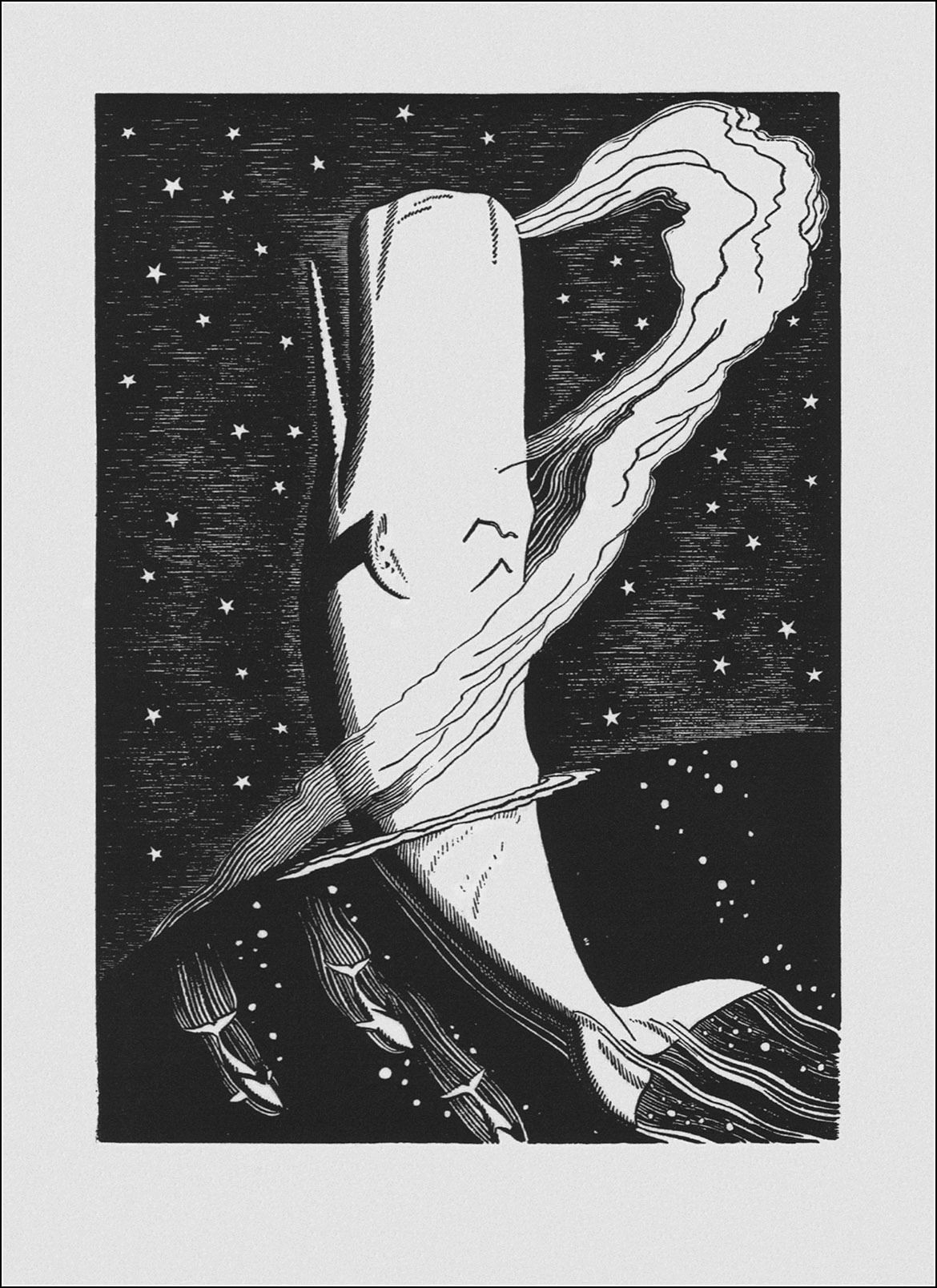

MS: I used the Barnes & Noble reprint of the old Henry Morley translation, revised by Lauren Walsh. I am not too fussy about translations and this one is fine. But the number one reason I got this edition is that it features the excellent illustrations of Alan Odle, a sort of Bloomsbury precursor of Ralph Steadman. I don’t know much about him but his sense of the grotesque was unique. An inspired choice of illustrator for this text. The cover price of $4.95 also influenced my decision.

I’ve read Candide in French and Morley is a bit more turgid than The Master … Voltaire’s French is slightly flatter and lighter. My French is not very good, most Francophones freak out when they hear me mangling their mother tongue. They are more touchy about that than Anglophones, which probably explains why English is the global lingua franca, ha!

Even people who don’t speak a word of French freak out when I do so. Must be the moustache, like watching Saddam Hussein doing his cocktail party impression of Pepe le Pew. You WILL laugh.

Biblioklept: I first read Candide in Lowell Bair’s translation, with some awfully bawdy illustrations (by Sheilah Beckett) that left an indelible mark on me. The book zapped me. I was in the 10th grade and I didn’t know that such literature existed—that serious literature, like, the lit that the English teacher assigned could be like Marvel Comics, with folks dying in wild ways and then coming back to life. I want to come back to illustrations in Candide in a bit, but I’m curious about your first encounter with the book…

MS: After a bit of internet poking, I found some samples of your Candide illustrator, Sheilah Beckett, and was very impressed. That old-fashioned, fluid American draftsmanship, I love it. I did some more poking and found the first Candide I read, probably when I was about 12 years old, the Washington Square Press paperback with Zadig included, translator Tobias Smollett. I remember enjoying both stories as amazingly fast-paced ripping yarns. I was also a Gulliver’s Travels fan and Smollett must have made the connection even stronger.

My father was an English professor so our home was a bookworm’s paradise, he had a home and office library. I had read pretty widely in the classics by then and I remember sensing that there was something hidden behind the surface in Voltaire, not quite accessible to a kid and thus even more intriguing. The authorial perversity of punishing the hero and allowing the wicked to prosper without ever once doing something about it, it was very adult … but clearly not the standard-issue adult of 1960s-70s America.

That is the genius of Voltaire, when it comes to ideas AND execution, he is perpetual beta. The Enlightenment still inspires fear and loathing in most quarters, the drooling imbecility of contemporary politics and mass-media is proof positive of that.

Biblioklept: The drooling imbecility of contemporary politics and mass-media is what makes American Candide a possible book, a funny book, but also, I think, a somewhat sad book.

MS: I made a reader laugh and weep simultaneously, success at last! The original Candide was also black-humored but at least Voltaire’s readers could hope that their on-going Enlightenment was going to change things. We know nothing’s changed that much and American Candide wallows in that particular Slough of Despond. We are a drooling species of slack-jawed idiots and the more we try to clean up, the more we smear ourselves filthy.

The core message of the Enlightenment is thinking-for-yourself, as clearly and simply as possible. It’s very difficult, no matter how clever we think we are, it’s genuine hard work and we are a profoundly lazy and shiftless species. You will never get a majority of Homo sapiens to simultaneously think logically about anything (especially in voting booths). We only think in disorganized spurts, usually on our own and in the privacy of our own homes, just in case any other monkeys are snooping around, looking for easy egg-head prey.

The current American political mess is just mass cognition waxing and waning in a natural cycle, it’s not an American thing, it’s a human thing. The wicked revel in their cleverness while the mob cheers them on, despite the hurt it does them … that’s as old as the Peloponnesian War. At some point, things will improve, probably after considerable pain and suffering for those who least deserve it and most tried to get out of its way. A clinching argument to prove the suitability of god’s plan for us if you think god was made in the human image.

Life’s a bummer but perhaps after we struggle and suffer all our lives for mostly nothing in particular, we’ll die and be reborn as cute puppies or cuddly kittens. That’s what religion’s about, mostly … it is all a bit sad, I agree, but it could be even worse — what if all the rubbish inside people’s heads was actually true?

So let’s count our blessings and laugh, laugh, laugh!

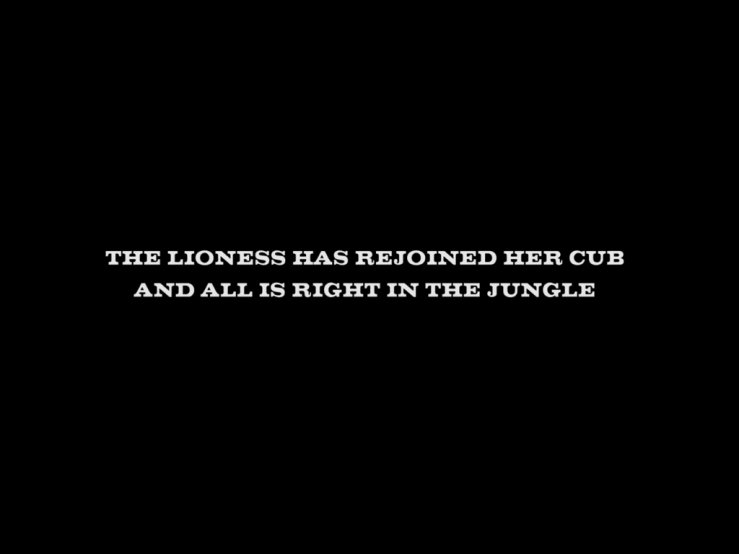

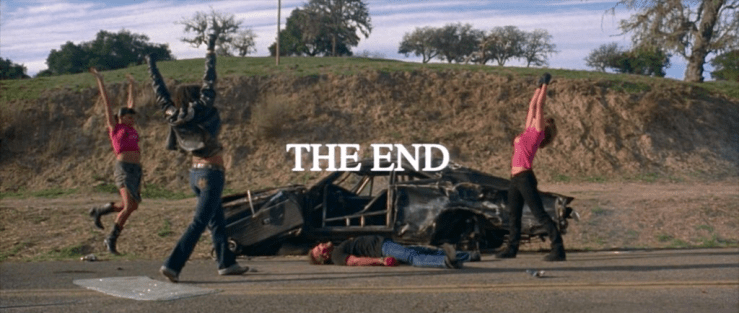

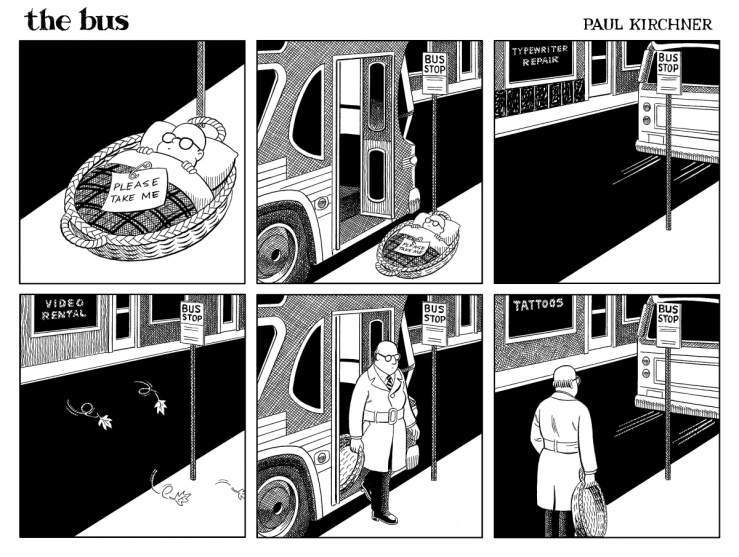

The book ends in 2015; I’ll let Mahé’s image speak for itself:

The book ends in 2015; I’ll let Mahé’s image speak for itself: