About halfway through Mahendra Singh’s American Candide, our omniscientish (yet beguiled) narrator slows down for a moment to offer an internal critique (and useful summary) of the novel thus far:

If Candide could address the reader right now, he would probably apologize for both the breakneck pace and pixelated tenor of his adventures so far. Modern literature evolved beyond that sort of thing long ago, and an easy-to-swallow plot enlivened with a soupçon of ironic handwringing is all the rage today. The idea of a fictional hero running afoul of angry fathers, jihadi terrorists, secret police, corporate mercenaries, a cable TV network, and a secret cabal of global warmers simply boggles the reader’s mind, an authorial fate worse than death.

And yet of course many readers enjoy a good mind boggling every now and then.

I do, anyway.

Our narrator’s little condensation of the novel thus far reminds us that stylistically and formally, American Candide is a true heir to Voltaire’s Candide. Both novels offer a “breakneck pace and pixelated tenor”; both novels pulse with picaresque energy; both novels drip with delightfully venomous satiric acid; both novels are basically one-damn-thing-happening-after-another. Both novels are funny as fuck all.

Our narrator’s quick summary also jabs at the limitations of contemporary socially-conscious-realistic fiction—you know, “serious literature”—which limitations American Candide dispenses with in favor of frenzied fun. Instead of a soupçon of ironic handwringing, we get full-blown glorious agitation.

What’s all the agitation over?

American Candide’s full title is American Candide; or Neo-Optimism, a direct nod to Voltaire’s full title, Candide; or Optimism. But Singh’s subtitular prefix points to other connotations: Neoliberalism, neoconservatism—hell, neofascism—but most of all, the irony that very little of human nature really has changed in three centuries. The big ideals of the Enlightenment continue to radiate too radically for some folks.

To wit, American Candide carves sharply into the last two decades, synthesizing the dangerous follies of the Bush Gang (and the subsequent fallout of their crimes) into a kind of mythical transposition. Singh offers a cruel fun satire of the neo-optimism that underwrites blind belief in “the better-than-best of all possible worlds, 21st-century America”. The novel’s satirical sting is simultaneously sweetened by intense humor and painfully amplified by the cruel realism underneath Singh’s zany hyperbole. Tell all the truth but tell it slant, as the poet advised.

And so American Candide is terribly terribly funny but also terribly terribly sad.

For example, Singh’s take on Hurricane Katrina shows American Candide’s capacity to condense historical critique into sharp moments that bristle with anger leavened in caustic humor:

The offending hurricane was clearly an act of god, and the Freedonian government prided itself on its special relationship with god.

Another snippet (“Hooterville” is New Orleans’s Freedonian stunt double):

The winds howled, the clouds unleashed a torrential rain, and the fetid waters of an entire ocean climbed over the heads of those surviving Hootervillains too patently lazy to live on higher ground.

Just a page or two later, Candide and Pangloss mistake armed and uniformed authorities for civil peacekeepers:

Rah! Ooh! We’re better than best police! … We’re Tender-Mercynaries® from Baron Incorporated, booyah, and this is a federally-restricted emergency disaster area, yoot-yoot rah booh!

Instead of helping our heroes, the mercenaries abduct, torture, and interrogate them. Candide and Pangloss find themselves in black hoods at a black site, and even though our young hero “had been lightly sodomized and beaten and even urinated upon…his innermost Freedonian convictions had not been too badly shaken.”

It’s the reader who shakes, in a mix of laughter and rage. The world of American Candide is simply our own world dressed up in a satirical frock that somehow reveals, rather than covers over, our society’s garish ugliness, our addictions to binding illusions. Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains, commented Rousseau (Voltaire hated Rousseau).

American Candide’s blurb warns that, “College-boy sissies will call it a Juvenalian satire upon America’s penchant for mindless optimism and casual racism.” Hooray for college-boy sissies! But no, really, I think that’s a fair assessment—as is Singh’s Candide’s assessment from the aforementioned blurb: “rage against the rage, Voltaire-dude!”

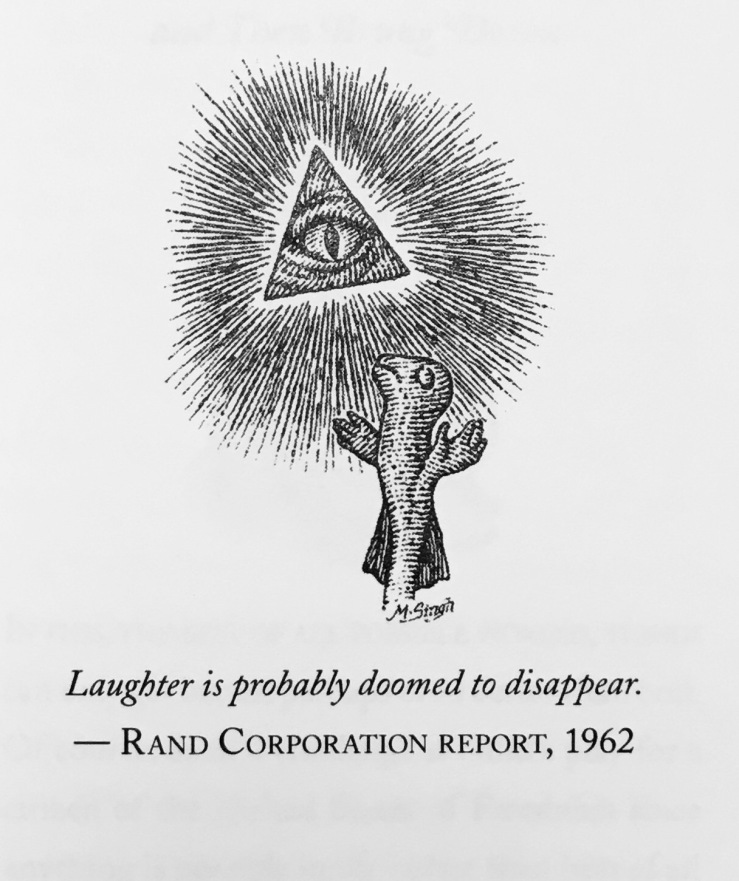

But it’s not just rage: Laughter—laughter in the all-seeing eye of absurdity—it’s laughter that undergirds American Candide.

In a review of Lowell Blair’s translation of Voltaire’s Candide, I suggested:

The book’s longevity might easily be attributed to its prescience, for Voltaire’s uncanny ability to swiftly and expertly assassinate all the rhetorical and philosophical veils by which civilization hides its inclinations to predation and evil. But it’s more than that. Pointing out that humanity is ugly and nasty and hypocritical is perhaps easy enough, but few writers can do this in a way that is as entertaining as what we find in Candide.

Singh’s update-reboot-translation of Candide fittingly answers Voltaire’s pessimistic prescience with not just bitter affirmations of contemporary predation and evil, but also with an eye toward entertainment—to the affirmations of laughter.

[Note: All the illustrations in this review are by Mahendra Singh, and are part of American Candide].