I took a few paperback books with me when I went camping two weeks ago, but I didn’t actually read from them. Instead, I wound up reading (or rereading in some cases) a few of the tales in Stephen Crane’s collection The Open Boat and Other Stories, which I downloaded from Project Gutenberg onto my iPad thanks to a data connection from my phone. Rain was pouring down on my tent and for some reason, I want to reread “The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky,” popped into my head, so I made it happen. I don’t know how these details are germane to anything I am trying to say here.

What I am trying to say here is that I didn’t read “The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky” right away. Instead, I read a story I’d never read before, “A Man and Some Others.” This tale contains some of the most fantastic sentences I’ve read in ages. (This is what I’m trying to say here: That “A Man and Some Others” contains some magical fucking prose).

Here is the opening paragraph:

Dark mesquit spread from horizon to horizon. There was no house or horseman from which a mind could evolve a city or a crowd. The world was declared to be a desert and unpeopled. Sometimes, however, on days when no heat-mist arose, a blue shape, dim, of the substance of a spectre’s veil, appeared in the south-west, and a pondering sheep-herder might remember that there were mountains.

I confess that I might have had some beers and Bushmills that evening, but I read and reread the opening sentences of “A Man and Some Others” in a little loop, hypnotized by the way Crane’s prose collapses human agency into an overwhelming naturalism—a naturalism with just the slightest Romantic touch of “a spectre’s veil.” (In “The Open Boat,” Crane demonstrates a more masterful and more complete grappling of naturalism resisting (and perhaps ultimately synthesizing) the Romantic traces of his transcendentalist forebears. But that’s a topic for another riff).

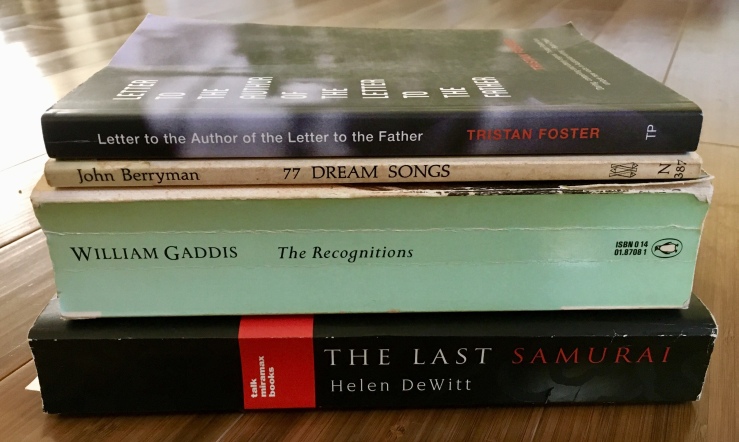

“A Man and Some Others” is about a cowboy named Bill. Threatened off a range that he claims as his own by Mexican ranchers who see otherwise, Bill retaliates. Along the way he meets a stranger—a stand-in for Crane, perhaps—who bears witness to the whole fandango. As a story, “A Man and Some Others” is slight, a thin premise that exists primarily as a space for Bill to swagger around in for a few pages. Sure, there could be a critique of Manifest Destiny somewhere in there, but Crane’s tale never coheres into a fully realized allegory or satire (as the poet John Berryman pointed out in his study of Crane, “Crane‘s humor, finally, and his irony are felt as weird or incomprehensible.” Berryman was referring to War Is Kind, but the description fits here as well).

Crane’s humor and irony are on vivid display in the six paragraphs that make up the second short chapter of “A Man and Some Others.” In this section, we get the improbable and wild life story of Bill, which reads on the one hand as a hyperbolic archetype of American machoism, a kind of fabulous legend of Manifest Destiny. On the other hand, Bill’s bio strikes the reader as so thoroughly and lovingly true that it seems Crane must have wholly plagiarized the life of a real individual (or at least combined a few wild but true stories from a handful of folks).

I won’t comment any further, but instead offer those six paragraphs, which I simply could never improve upon:

Bill had been a mine-owner in Wyoming, a great man, an aristocrat, one who possessed unlimited credit in the saloons down the gulch. He had the social weight that could interrupt a lynching or advise a bad man of the particular merits of a remote geographical point. However, the fates exploded the toy balloon with which they had amused Bill, and on the evening of the same day he was a professional gambler with ill-fortune dealing him unspeakable irritation in the shape of three big cards whenever another fellow stood pat. It is well here to inform the world that Bill considered his calamities of life all dwarfs in comparison with the excitement of one particular evening, when three kings came to him with criminal regularity against a man who always filled a straight. Later he became a cow-boy, more weirdly abandoned than if he had never been an aristocrat. By this time all that remained of his former splendour was his pride, or his vanity, which was one thing which need not have remained. He killed the foreman of the ranch over an inconsequent matter as to which of them was a liar, and the midnight train carried him eastward. He became a brakeman on the Union Pacific, and really gained high honours in the hobo war that for many years has devastated the beautiful railroads of our country. A creature of ill-fortune himself, he practised all the ordinary cruelties upon these other creatures of ill-fortune. He was of so fierce a mien that tramps usually surrendered at once whatever coin or tobacco they had in their possession; and if afterward he kicked them from the train, it was only because this was a recognized treachery of the war upon the hoboes. In a famous battle fought in Nebraska in 1879, he would have achieved a lasting distinction if it had not been for a deserter from the United States army. He was at the head of a heroic and sweeping charge, which really broke the power of the hoboes in that country for three months; he had already worsted four tramps with his own coupling-stick, when a stone thrown by the ex-third baseman of F Troop’s nine laid him flat on the prairie, and later enforced a stay in the hospital in Omaha. After his recovery he engaged with other railroads, and shuffled cars in countless yards. An order to strike came upon him in Michigan, and afterward the vengeance of the railroad pursued him until he assumed a name. This mask is like the darkness in which the burglar chooses to move. It destroys many of the healthy fears. It is a small thing, but it eats that which we call our conscience. The conductor of No. 419 stood in the caboose within two feet of Bill’s nose, and called him a liar. Bill requested him to use a milder term. He had not bored the foreman of Tin Can Ranch with any such request, but had killed him with expedition. The conductor seemed to insist, and so Bill let the matter drop.

He became the bouncer of a saloon on the Bowery in New York. Here most of his fights were as successful as had been his brushes with the hoboes in the West. He gained the complete admiration of the four clean bar-tenders who stood behind the great and glittering bar. He was an honoured man. He nearly killed Bad Hennessy, who, as a matter of fact, had more reputation than ability, and his fame moved up the Bowery and down the Bowery.

But let a man adopt fighting as his business, and the thought grows constantly within him that it is his business to fight. These phrases became mixed in Bill’s mind precisely as they are here mixed; and let a man get this idea in his mind, and defeat begins to move toward him over the unknown ways of circumstances. One summer night three sailors from the U.S.S. Seattle sat in the saloon drinking and attending to other people’s affairs in an amiable fashion. Bill was a proud man since he had thrashed so many citizens, and it suddenly occurred to him that the loud talk of the sailors was very offensive. So he swaggered upon their attention, and warned them that the saloon was the flowery abode of peace and gentle silence. They glanced at him in surprise, and without a moment’s pause consigned him to a worse place than any stoker of them knew. Whereupon he flung one of them through the side door before the others could prevent it. On the sidewalk there was a short struggle, with many hoarse epithets in the air, and then Bill slid into the saloon again. A frown of false rage was upon his brow, and he strutted like a savage king. He took a long yellow night-stick from behind the lunch-counter, and started importantly toward the main doors to see that the incensed seamen did not again enter.

The ways of sailormen are without speech, and, together in the street, the three sailors exchanged no word, but they moved at once. Landsmen would have required two years of discussion to gain such unanimity. In silence, and immediately, they seized a long piece of scantling that lay handily. With one forward to guide the battering-ram, and with two behind him to furnish the power, they made a beautiful curve, and came down like the Assyrians on the front door of that saloon.

Mystic and still mystic are the laws of fate. Bill, with his kingly frown and his long night-stick, appeared at precisely that moment in the doorway. He stood like a statue of victory; his pride was at its zenith; and in the same second this atrocious piece of scantling punched him in the bulwarks of his stomach, and he vanished like a mist. Opinions differed as to where the end of the scantling landed him, but it was ultimately clear that it landed him in south-western Texas, where he became a sheep-herder.

The sailors charged three times upon the plate-glass front of the saloon, and when they had finished, it looked as if it had been the victim of a rural fire company’s success in saving it from the flames. As the proprietor of the place surveyed the ruins, he remarked that Bill was a very zealous guardian of property. As the ambulance surgeon surveyed Bill, he remarked that the wound was really an excavation.