1. Let’s start with the what:

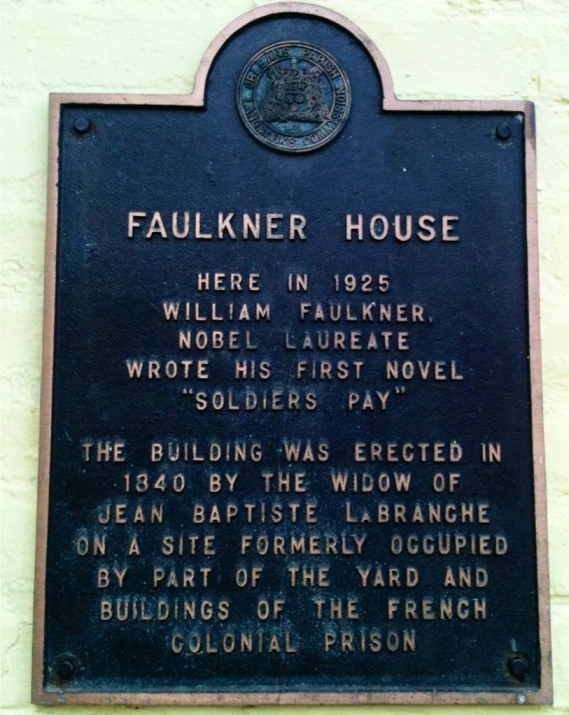

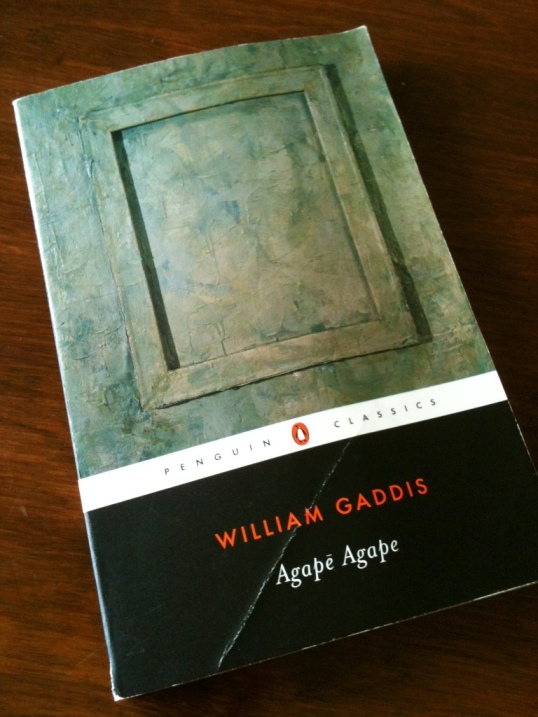

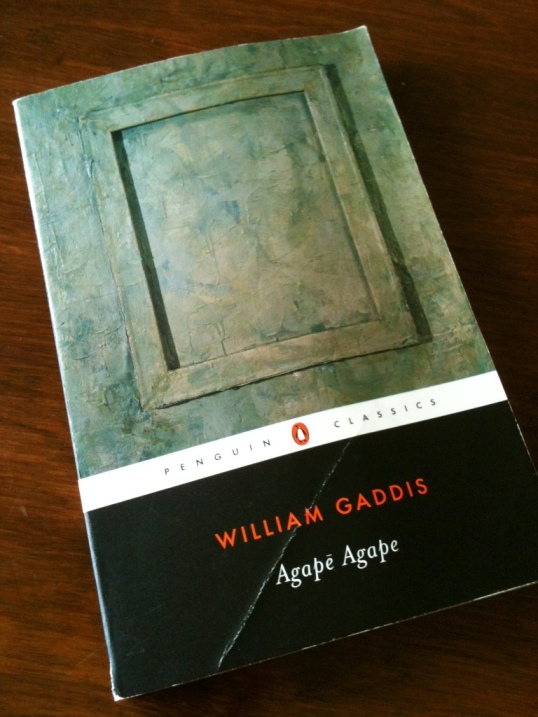

Agapē Agape is the last novel by William Gaddis, that underread titan who gave us The Recognitions and J R. Agapē Agape was published in 2002, four years after Gaddis’s death. Agapē Agape is 96 pages in my Penguin Classics edition (the font is rather large, too)—almost exactly one-tenth the length of The Recognitions in my Penguin Classics edition, which is 956 pages (and in a smaller font).

2. And why?

Let’s say I’ve struggled with this review, perhaps more than I struggled with writing about J R (which I did here and here) or The Recognitions (which I did here and here), which seems nonsensical because those books are so big and this one is so short. But that’s a surface argument.

See, Agapē Agape is dense. It seems to compact and condense all of Gaddis’s themes and ideas and motifs into this little book that’s uranium heavy, too dense to allow for line breaks or paragraph breaks or indentations, let alone chapters. It’s one big block of text.

3. And so—

After reading the book twice I’ve marked every page (which is exactly like marking no pages), and at this point the only way that I can find to discuss it (I know there must be others) is to annotate the opening paragraph, its first sentence, really—which of course isn’t really a paragraph or a sentence in the traditional grammatical sense—I mean, there are a set of clauses, some fused sentences, perhaps a comma splice or two—but what marks it as a discrete sentence is that it’s punctuated by a question mark, a tiny caesura before the next onslaught of words. (Some of Agapē Agape’s sentences go on for pages).

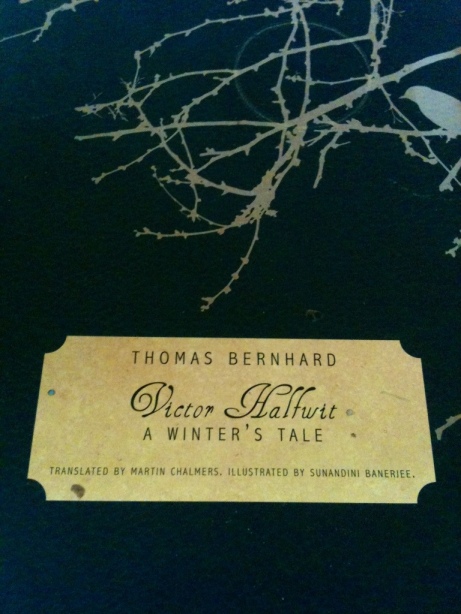

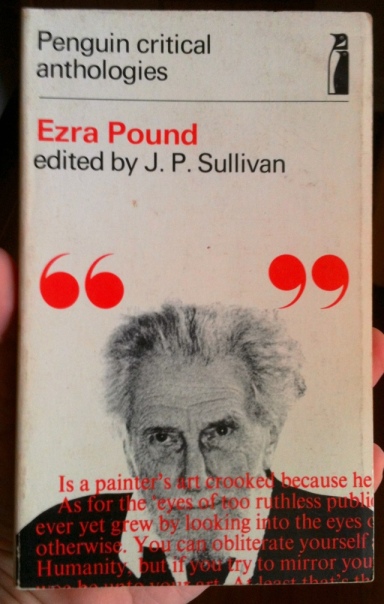

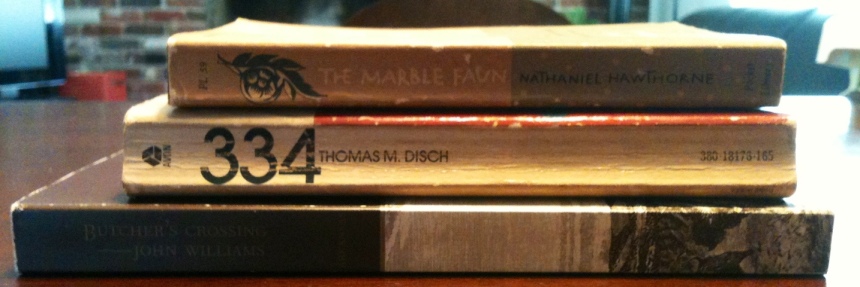

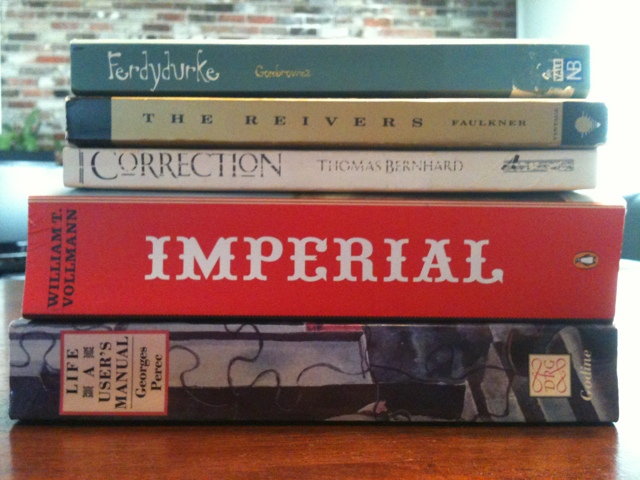

4. The style of Agapē Agape recalls Thomas Bernhard, who Gaddis’s narrator accuses of having plagiarized the book that the narrator has yet to write. The accusation (ironic, purposefully, of course) points to Agapē Agape’s concern for synthesis, for transmitting some clear thesis statement out of the muddle of Western culture. Agapē Agape tries to suss out that muddle and as such is larded with discussions of Plato, Nietzsche, Melville, Hawthorne, Byron, Freud (“Sigi”!), Bach, Caesar, Joyce, Pulitzer, Tolstoy, Frankenstein, Huizinga, Pound, Philo T. Farnsworth, player-pianos . . . It overwhelms the narrator; it overwhelms the reader. But enough dithering—

5. —here is the opening sentence:

No but you see I’ve got to explain all this because I don’t, we don’t know how much time there is left and I have to work on the, to finish this work of mine while I, why I’ve brought in this whole pile of books notes pages clippings and God knows what, get it all sorted and organized when I get this property divided up and the business and worries that go with it while they keep me here to be cut up and scraped and stapled and cut up again my damn leg look at it, layered with staples like that old suit of Japanese armour in the dining hall feel like I’m being dismantled piece by piece, houses, cottages, stables orchards and all the damn decisions and distractions I’ve got the papers land surveys deeds and all of it right in this heap somewhere, get it cleared up and settled before everything collapses and it’s all swallowed up by lawyers and taxes like everything else because that’s what it’s about, that’s what my work is about, the collapse of everything, of meaning, of values, of art, disorder and dislocation wherever you look, entropy drowning everything in sight, entertainment and technology and every four year old with a computer, everybody his own artist where the whole thing came from, the binary system and the computer where technology came from in the first place, you see?

6. “No but you see I’ve got to explain all this because I don’t, we don’t know how much time there is left and I have to work on the, to finish this work of mine while I,”

Ulysses ends with a “Yes”; Agapē Agape begins with a “No.” This is a deeply negative book, cruel almost, bitter, caustic, acidic, but also erudite, funny, and even charming. We see right away the narrator—surely a version of Gaddis himself—concerned with the ancient problem of communication, the problem that occupied Plato and every philosopher since: “I’ve got to explain all this.” We also see here the same stream-of-consciousness technique here that Joyce used so frequently in Ulysses (putting aside Gaddis’s denials of a Joyce influence)—the suspended referent, the unnamed (the unnameable?): “I have to work on the, to finish this work of mine while I”—while I what? Still can? Still live? From the outset, Agapē Agape is a contest against time, death, and entropy.

7. “why I’ve brought in this whole pile of books notes pages clippings and God knows what, get it all sorted and organized”

Synthesis, synthesis, synthesis. Making books out of other books. Plugging literature into other literature. I am quite content to go down to posterity as a scissors-and-paste man, said someone once. And then others said it again. And then I cited it here, now.

I’m reminded here of a list that Gibbs (erstwhile Gaddis stand-in in J R) keeps in his pocket, a scrap paper crammed with ideas, fragments, citations:

Is it possible to get it sorted?

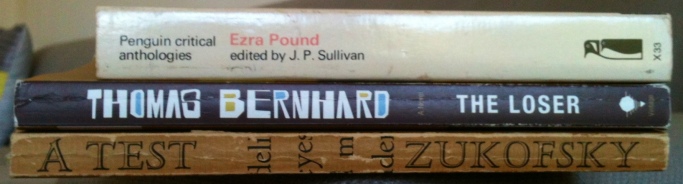

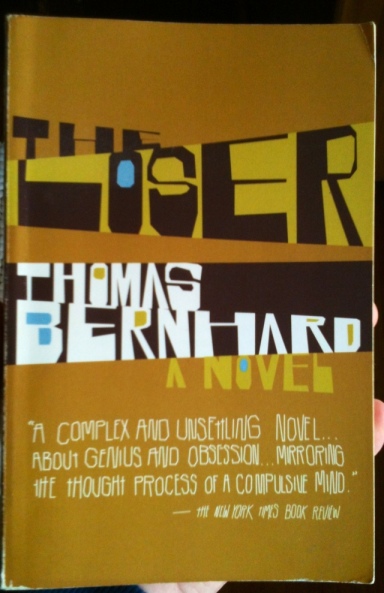

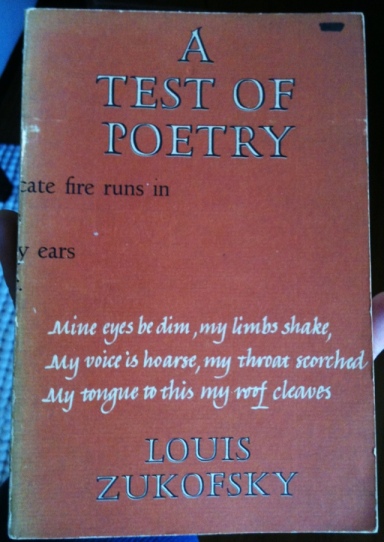

Recall now Gaddis’s hero Ezra Pound. From Tom McCarthy’s essay on synthesis, “Transmission and the Individual Remix”:

With the Cantos, he kept up this furious enterprise for five whole decades, ramping its intensity up and up until the overload destroyed him, blew his mind to pieces, leaving him to murmur, right toward the end: “I cannot make it cohere.”

It is the reader’s job to make Agapē Agape cohere.

8. “when I get this property divided up and the business and worries that go with it”

Agapē Agape may be said to have a few formalizing plots beyond its object of synthesizing Western culture vis-à-vis art and entertainment.

One of these formalizing elements is the idea of an old man divvying up his property to his daughters. Oh, hey, King Lear anyone? What’s most interesting to me about this plot (okay, more of a motif really) is that it’s the only allusive device that the narrator doesn’t remark upon. We have a narrator who’s trying to control all these notes and clippings, all these scraps of culture, a narrator with a sharp (if distracted intelligence) who nevertheless fails to remark upon the fact that his personal circumstances echo the great dismal swan song of English literature. King Lear: madness, unraveling, degeneracy, death, entropy.

9. “while they keep me here to be cut up and scraped and stapled and cut up again my damn leg look at it, layered with staples like that old suit of Japanese armour in the dining hall feel like I’m being dismantled piece by piece,”

Another formalizing element in Agapē Agape are the health issues the narrator faces, presumably a series of surgeries that involve at least one of his legs. The motif of surgeries, of transplants, and implants runs throughout The Recognitions and J R as well. In The Recognitions we get poor Stanley’s mother’s amputated leg, another strange reliquary trace floating through the text. In J R, we get Cates prepped for a heart transplant, yet another organ transferral for this massive man. There’s the idea here of borrowed parts, that humans might not be “natural,” cohesive entities but rather a collection of parts that may be swapped out. Again, synthesis in the face of break down; the surgeon as entropy repairman.

10. “houses, cottages, stables orchards and all the damn decisions and distractions I’ve got the papers land surveys deeds and all of it right in this heap somewhere, get it cleared up and settled before everything collapses and it’s all swallowed up by lawyers and taxes like everything else because that’s what it’s about,”

Here, the personal, the concrete, the immediate, and the real tips into what Gaddis took to be the grand subject of his corpus—collapse, chaos, entropy. Spelled out clearly in the next line:

11. “that’s what my work is about, the collapse of everything, of meaning, of values, of art, disorder and dislocation wherever you look, entropy drowning everything in sight,”

I don’t think commentary from me is necessary here. Instead, let me share a quote from Gibbs in J R, ranting to his young students:

Before we go any further here, has it ever occurred to any of you that all this is simply one grand misunderstanding? Since you’re not here to learn anything, but to be taught so you can pass these tests, knowledge has to be organized so it can be taught, and it has to be reduced to information so it can be organized do you follow that? In other words this leads you to assume that organization is an inherent property of the knowledge itself, and that disorder and chaos are simply irrelevant forces that threaten it from the outside. In fact it’s the opposite. Order is simply a thin, perilous condition we try to impose on the basic reality of chaos . . .

12. “entertainment and technology and every four year old with a computer, everybody his own artist where the whole thing came from, the binary system and the computer where technology came from in the first place, you see?”

The age of the amateur. Paint-by-numbers. Everyone wants to write a novel but no one wants to read one. Etc. When the narrator grumbles “where technology came from in the first place,” he means entertainment. That’s one thesis in Agapē Agape: that the technological progress we so value, that so underwrites the march of our grand civilization has its roots in toymaking and child’s play.

13. The novel that follows this addled, rattled opening line is remarkable for its brilliance, its cruelty, but most of all its sheer verbal force. Gaddis showed a mastery of voice in J R, a heteroglossic novel of speech, speech, speech, a grand dare to any reader, I suppose. Agapē Agape is even more stripped down, the monologue of a dying voice, a voice that’s been too-long ignored and under-appreciated. I don’t know if something so sad, so personally sad can be called perfect, but I can’t think of a more appropriate or fitting final statement from Gaddis.