Boring preamble you’ll likely skim if not outright skip:

I was never going to get a full year end list thing together. Yesterday I put together a list of books I read in full this year, or at least books I remember reading in full. In full and books are terms that should be placed under suspicion. For example, it took me far longer to get eighty pages into William H. Gass’s The Tunnel—a novel I soon after abandoned—than it did to read Robert Coover’s micronovella The Enchanted Prince or Dave Cooper’s graphic novel Mudbite. Etc. As usual I abandoned more novels than I finished, and read more short stories than I could or should bother listing.

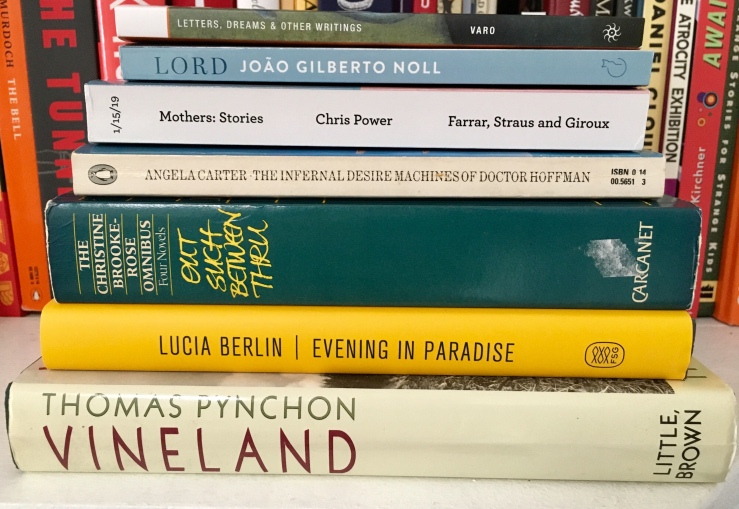

Annotations on a probably incomplete list of books I read or reread in full in 2018:

Barracoon by Zora Neale Hurston (2018)

A sad and important book, too long unpublished. I reviewed it here.

Conversations with Gordon Lish edited by David Winters and Jason Lucarelli (2018)

One of the best things I read in 2018. Lish performing Lish throughout the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first. As good, if not better, than his short fiction.

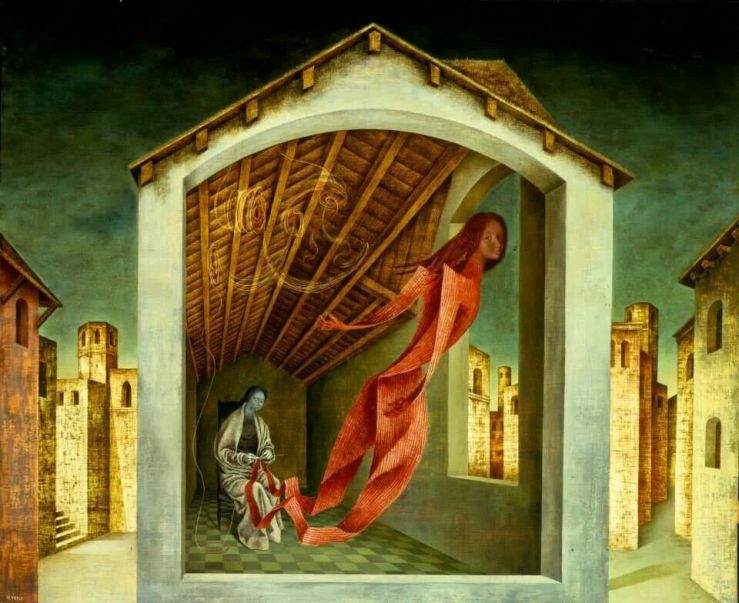

Dreamverse by Jindřich Štyrský (2018 English translation by Jed Slast; original Czech-language publication in 1970)

Abject horny surrealist art and poetry. I wrote about it here.

The Enchanted Prince by Robert Coover (2018)

Going for a Beer: Selected Short Fictions by Robert Coover (2018)

The Enchanted Prince is a quick read, and wouldn’t be out of place in an extended edition of Going for a Beer. I failed to write about Going for a Beer, after mucking around with several drafts. I had a big thing on “The Babysitter” that I was working on—it being a perfect nexus of horror and comedy, a writhing, icky pop opera of channel changing. I kept thinking of “The Babysitter” during the Brett Kavanaugh hearing, and managed to write absolutely nothing in my disgust. Going for a Beer is a perfect starting place for Coover, although some of the moves in it grow tiresome. The metamagician takes us aside a bit too often to show us how he did the trick, only to tell us that his showing us how he did the trick was actually the trick itself.

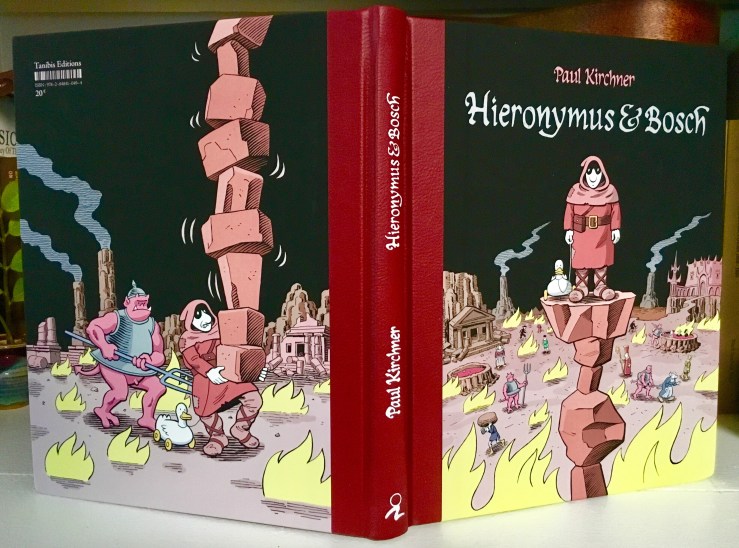

Hieronymus & Bosch by Paul Kirchner (2018)

The Labyrinth by Saul Steinberg (2018; originally published in 1960)

Both wonderful “graphic novels,” or not really “novels,” but something else. I should have reviews of these posted at The Comics Journal in early 2019.

The Largesse of the Sea Maiden by Denis Johnson (2018)

A perfect farewell to Johnson. I read it twice, and wrote about the title story, second story, “The Starlight on Idaho,” and the third,“Strangler Bob.”

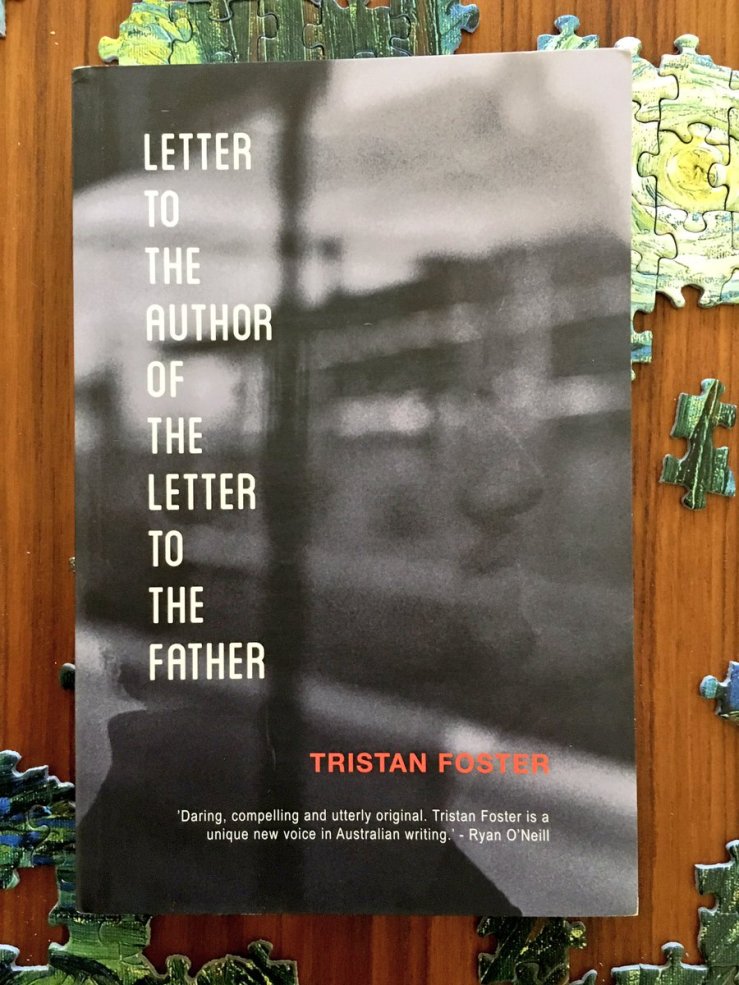

Letter to the Author of the Letter to the Father by Tristan Foster (2018)

Great stuff. I finished a bigass novel yesterday so now I can reread Foster’s strange fictions and write a proper review.

Moderan by David R. Bunch (2018; originally published in incomplete form in 1971)

I’ll admit I’d never heard of Bunch’s dystopian cult Moderan stories until NYRB reprinted them in a complete volume this year. Moderan works as a post-nuke dystopian satire on toxic masculinity. The tropes here might seem familiar—cyborgs and dome homes, caste systems and ultraviolence, a world of made and not born ruled by manunkind (to steal from E.E. Cummings)—it’s the way that Bunch conveys this world that is so astounding. Moderan is told in its own idiom; the voice of our narrator Stronghold-10 booms with a bravado that’s ultimately undercut by the authorial irony that lurks under its surface. The book seems equal to the task of satirizing the trajectory of our zeitgeist in a way that some contemporary satirists have failed to.

Mudbite by Dave Cooper (2018)

Lurid, abject, horny, gross. I dug it. I reviewed it at The Comics Journal.

Narcotics by Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (2018 English translation by Soren Gauger)

Another oddball from the good folks at Twisted Spoon Press. I reviewed it here.

On Doing Nothing by Roman Muradov (2018)

Muradov’s riffs on literature, art, and philosophy to add to the American tradition of leaning and loafing at one’s ease, observing a summer spear of etc.

Provisional Biography of Mose Eakins by Evan Dara (2018)

An overlooked work by an overlooked writer, Provisional Biography isn’t quite as persuasive as its predecessor, Flee, but it’s nevertheless a strong argument for communication in/against the age of late capitalism. I reviewed it here.

Slum Wolf by Tadao Tsuge (2018 English translation by Ryan Holmberg)

This collection of “alternative manga” (from The New York Review of Books’ NYRC imprint) showcases nine rough and seedy stories focused on the kimin, the “abandoned people” who live on the margins of Japanese society. Under Tsuge’s mean humor is a diamond-sharp kernel of pathos for all humanity, rendered in spare, even rushed art. Tsuge draws as if his ink and paper might be snatched away at any moment by some civilizing agent who would keep his slum wolves away from respectable eyes. His world isn’t pretty but it is somehow beautiful.

The Snail on the Slope by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky (2018 English translation by Olena Bormashenko; original Russian-language translation, 1972)

An impossibly strange book, an utter revelation, just so astoundingly weird. I wrote about it here.

Stream System by Gerald Murnane (2018)

Murnane made a dent into an American mainstream audience this year with Stream System (complete with a fascinating feature in The New York Times). The early stories are particularly affecting. I wrote about one here.

Pond by Claire-Louise Bennett (2015)

Pond was one of the best things I read this year. I wrote about it here.

The Truce by Mario Benedetti (2015 English translation by Harry Morales; original Spanish-language publication, 1960)

Benedetti’s The Truce is good old fashioned mannered modernism. I couldn’t really get into it, although the novel’s voice is authentic. It reminded me of Williams’ Stoner a bit.

Post-Exoticism in Ten Lessons, Lesson Eleven by Antoine Volodine (2015 English translation by J. T. Mahany; original French-language publication, 1998)

Definitely Maybe by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky (2014 English translation by Antonina Bouis; original Russian-language translation, 1974)

Writers by Antoine Volodine (2014 English translation by Katrina Rogers; original French-language publication, 2010)

Minor Angels by Antoine Volodine (2008 English translation by Jordan Stump; original French-language publication, 2004)

I’ve arranged this list by year, and the Volodines are almost grouped together, with the Strugatskys interposing. Definitely Maybe is okay but not excellent—it’s a fun and ultimately tense read, evocative of hot drunken times and philosophical murders.

Antoine Volodine wrote some of the best stuff I read this year. Post-Exoticism or Writers would make excellent starting places for anyone interested in his grim, stark (and often unexpectedly funny) world. I wrote about Writers here and here.

The Last Samurai by Helen DeWitt (2000)

I didn’t really like Lightning Rods and I wished I hadn’t paid twenty bucks for Some Trick in hardback, but enough people I respect have been telling me (directly and indirectly) to read DeWitt’s cult novel debut that I didn’t hesitate to pick up a copy when I found it used in my favorite bookshop. I read The Last Samurai faster than any book I can remember. For a book often described as “experimental” or “formally challenging” it’s extraordinarily accessible and very “readable.” DeWitt’s rhetoric teaches the reader how to read the book; she creates a formula, essentially (Lighting Rods did the same, come to think of it). The Last Samurai has moments that are as transcendent as any of the other great books I read this year, but I’m not sure that it adds up to more than the sum of its parts. I enjoyed the reading experience though.

Carpenter’s Gothic by William Gaddis (1985)

I had never read Carpenter’s Gothic until this year (I still need to read A Frolic of His Own). I reread The Recognitions, and while its certainly a richer, denser, and frankly more overwhelming work, it isn’t as formally neat as Carpenter’s Gothic, which I think is ultimately the better book. I wrote about it here, here, and here.

The Names by Don DeLillo (1982)

Only a few fragments stick with me now—the end in particular—but also, the general impression that Don DeLillo wrote the first post-9/11 novel way back in 1982. I wrote about it here.

The Plains by Gerald Murnane (1982)

The first fifty or so pages of The Plains was as good as anything I read this year. I felt like I was hungry for more at the end though, but good authors sometimes leave us unsatisfied.

77 Dream Songs by John Berryman (1964)

I needed these.

The Bell by Iris Murdoch (1958)

This book has some excellent sentences, and Dora Greenfield is one of the more memorable characters I read this year. The Bell also prompted me to reread Hawthorne’s The Blithedale Romance, and I’m thankful to it for that. My first Murdoch. I’ll read more of hers in 2019. I wrote about The Bell here.

The Recognitions by William Gaddis (1955)

Reread the thing in tandem with an audiobook recording; the audiobook is pretty good, but mostly useful in the sense that it allows you to reread (or first read) as you go through. I think The Recognitions can’t be read—it can only be reread. I wrote about it here and here and here and here and here.

Middlemarch by George Eliot (1871)

A reading highlight of 2018. Dorothea Brooke is the most memorable character of my 2018 reading. I wrote about Middlemarch here and here.

Silas Marner by George Eliot (1861)

I liked this one a lot. I reviewed it here.

The Confidence-Man by Herman Melville (1857)

Benito Cereno by Herman Melville (1855)

The Confidence-Man remains a novel that I think I won’t ever fully “get.” Rereading it this year it seemed as puzzling as ever. We’ll see what happens when I read it again. Benito Cereno might have been my favorite reread of 2018; I wrote a long thing on it here. 2019 seems like a good year to go through Moby-Dick again.

The Blithedale Romance by Nathaniel Hawthorne (1852)

Another really enjoyable reread, with correspondences to Middlemarch and The Bell. I wrote a lot about Blithedale, including this post.

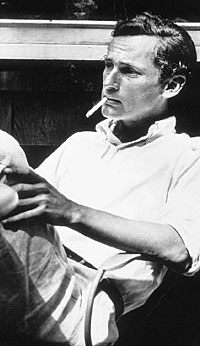

wrapper stood forth in stark configurations of red and black to intimate the origin of design. (For some crotchety reason there was no picture of the author looking pensive sucking a pipe, sans gêne with a cigarette, sang-froid with no necktie, plastered across the back.)

wrapper stood forth in stark configurations of red and black to intimate the origin of design. (For some crotchety reason there was no picture of the author looking pensive sucking a pipe, sans gêne with a cigarette, sang-froid with no necktie, plastered across the back.)