Notes on Chapters 1-7 | Glows in the dark.

Notes on Chapters 8-14 | Halloween all the time.

Notes on Chapters 15-18 | Ghostly crawl.

Notes on Chapters 21-23 | Phantom gearbox.

Notes on Chapters 27-29 | We’re in for some dark ages, kid.

Notes on Chapters 30-32 | Some occult switchwork.

Notes on Chapters 33-34 | The dead ride fast.

Notes on Chapters 35-36 | Ghost city.

Chapter 37: Shadow Ticket continues its wrap-up. Hicks punches another old ticket, not-exactly-solving the mystery of missing Stuffy Keegan (who disappeared way back in Ch. 8 on a U-13 submarine — a submarine that not everyone can see — into the icy depths of Lake Michigan.)

Hicks meets Stuffy at “the old Whitehead factory, where the torpedo as we have come to know it was invented.” The Whitehead Torpedo Works, based in Fiume/Rijeka invented and developed the self-propelled torpedo in the 1860s. After WWI the company (under different subsidiary names) manufactured motorcycles and then hand grenades — bikes and pineapples, in the parlance of Shadow Ticket. There are a lot of bombs and biwheels in this novel.

The Whitehead Torpedo Works is another of Shadow Ticket’s Gothic spots, “fallen into ruin [and] said to be haunted by the ghosts of submarines long dismantled.” The phantom submarine that Stuffy crews is supernatural, natch, and a totem of the bigger thesis that Pynchon underlines throughout his latest novel: It’s never too late to redeem yourself. A war machine might repurpose itself, friendly ghost, into a rescue ship (or at minimum, a do-no-harm ship).

Stuffy introduces Hicks to the submarine’s skipper, Ernst Hauffnitz a veteran of the Great War responsible for “no casualty count that I know of, idiot’s luck no doubt.” The idiot, the fool, is blessed in Pynchon’s oeuvre, and in Shadow Ticket especially. And the idiot-who-does-no-harm is especially blessed. Let’s consider Hicks’s past as a strikebreaker, which we learn about back in Ch. 4, in a pivotal encounter when the big gorilla goes to whack a “truculent little Bolshevik” with a “lead-filled beavertail sap” that would’ve surely killed the poor fella. Hicks’s blackjack disappears — “asported,” in the novel’s paranormal lingo. It sets him on a non-violent path (whether he sees or chooses this path or not).

For skipper Ernst Hauffnitz, doubts about the merits of war — by which I think we should say, doubts about using technology and innovation in the service of violence and undue death — began when “Max Valentiner torpedoed and sank SS Persia in the Mediterranean, killing 343 civilians in direct violation of Chancellery orders to spare passengers and rescue survivors.”

Those doubts increased when post-WWI orders to bring his submarine “to be broken up pursuant to Article 122 of the Trianon dictate“ led Captain Hauffnitz to suicidal feelings — but he converts that despair into hope, and sets out on a “new career of nonbelligerence.”

That new do-no-harm career includes helping out the Al Capone of Cheez, Bruno Airmont, “Who is about to be taken, as we speak, off on an undersea voyage of uncertain extent.” The International Cheese Syndicate — InChSyn — is after Bruno who’s taken off with their cash and their secrets. The submariners, now in “the search and rescue line” aim to see that “Mr. Airmont is safely relocated where he can neither commit nor incur further harm.”

Captain Hauffnitz continues: “You might consider us an encapsulated volume of pre-Fascist space-time, forever on the move, a patch of Fiume as it once was, immune to time, surviving all these years in the deep refuge of the sea…” On the move is the move of Shadow Ticket, one of its grand themes summed up by Stuffy Keegan back in Ch. 20: “as long as you can stay on the run, that’s the only time you’re really free.”

The episode concludes with reference to the “Valdivia Expedition of 1898–99, which brought up into the daylight a pitch-black critter known as the Vampire Squid, by whose name, these days, the U-13 has since come to be known.” More Gothic tinges!

We transition to the parting farewells of Bruno and Daphne; Daphne’s secured her father’s passage with a mariner named Drago. Papa Bruno gives his “li’l midnight pumpkin” a parting gift — “Better than money…It’s information” on the machinations of the InChSyn. Their last moments end with Bruno looking down at his watch, a “Rolex Oyster Perpetual he does not seem to recognize, as if thanks to the psychical ambience he’s been in all evening it has just apported onto his wrist.”

It’s an odd reference, Bruno’s phantom Rolex, but it also fits with the novel’s theme of time as well as the motif of timepieces. Way back in Ch. 1, Skeet Wheeler shows off his new watch to Hicks: “Hamilton, glows in the dark too.” We’ll get a reference to that timepiece in the last paragraphs of the novel.

Bruno doesn’t make it too far on Drago’s escape boat before Hauffnitz’s crew intervenes. He’s on their sub in no time, wondering if he’s imprisoned in his “not uncomfortable cabin” — “Is this the brig I’m in, he wonders. No, submarines don’t have brigs, they are brigs.”

Stuffy starts to explain the situation to Bruno; the Cheez Gangster at first believes that the crew of the Vampire Squid intend to turn him over to the InChSyn. But as we saw earlier in the chapter, their goal is to add to a world of do no harm.

Stuffy tries to hip Bruno to his new life: “See, there’s a difference between the Al Capone of Cheese and the AC of C in Exile. One sooner or later gets the paving-material overcoat. The other goes where he’ll do no harm. Our racket happens to be exile.”

The chapter ends with Stuffy hipping Bruno to the 1933 Wisconsin milk strikes:

Seems revolution has broken out in the U.S., beginning in Wisconsin as a strike over the price per hundredweight that dairy farmers were demanding for milk, spreading across the region and soon the nation. Milk shipments hijacked and dumped at trackside, trees felled across roadways and set aflame to stop motor delivery, all-night sentinels, crossroads pickets, roundups, ambushes, bayonet charges, gunfire, casualties military and civilian.

It’s easy to dismiss Pynchon’s evocation of American zaniness as goofy, silly, unserious — but that would require (the very easy threshold of) not actually really reading Pynchon, a writer whose works stand clearly on the side of organized labor as well as on the peace-anarchy dimension of do no harm. The notion of “milk strikes” and a gangster cheese magnate might seem wacky, but Pynchon’s narrator points us towards the wallet, the stomach, the soul. There’s something comforting in the idea of Midwestern dairy workers going hard as a motherfucker and taking collective action to resist exploitation a century ago.

Chapter 38: Who should Hicks run into on the Korzo but one-time mob-enforcer Dippy Chazz Foditto, recently deported from the USA but nevertheless “just signed on to a scheme hatched and run by U.S. ruling-class elements who are betting that the island of Sicily will be a strategic factor in the next war.” Dippy will help to establish “a local anti-Fascist guerrilla force, trained, armed, and ready to roll.” Again, we’re ramping up to WW2. Dippy Chazz brings news from the West: Hicks’s old flame April is now married to the head crimeboss Milwaukee, and pregnant to boot. Hicks is exiled: “Take the tip, is all, it’s over for you in M’waukee, Hicks, Chicago too.”

The chapter ends on a sad note, with Hicks, “in the dawn hours of the first day of a post-American life…dials a number without thinking much about it till later, when he remembers it’s a TRIangle exchange number in Chicago, same as Al Capone’s mother has.” We can recall from Ch. 4 that Hicks’s mother Grace abandoned him to run away with an elephant trainer. He has a conversation with a person — his mother? Capone’s? just a person? — that ends with the sad image of trying to find “just a glimpse of something blowing away into the night, something it’s already too late to chase in this windbeaten emptiness taking possession of his heart…”

Previously on Blue Lard…

Previously on Blue Lard…

In his

In his  According to Chamberlain, John Glanton was born in South Carolina and migrated to Stephen Austin’s settlement in Texas. There he fell in love with an orphan girl and was prepared to marry her. One day while he was gone, Lipan warriors raided the area scalping the elderly and the children and kidnapping the women- including Glanton’s fiancee. Glanton and the other settlers pursued and slaughtered the natives, but during the battle the women were tomahawked and scalped. Legend has it, Glanton began a series of retaliatory raids which always yielded “fresh scalps.” When Texas fought for its independence from Mexico, Glanton fought with Col. Fannin, and was one of the few to escape the slaughter of that regiment at the hands of the Mexican Gen. Urrea- the man who would eventually employ Glanton as a scalp hunter. During the Range Wars, Glanton took no side but simply assassinated individuals who had crossed him. He was banished, to no avail, by Gen. Sam Houston and fought as a “free Ranger” in the war against Mexico. Following the war he took up the Urrea’s offer of $50 per Apache scalp (with a bonus of $1000 for the scalp of the Chief Santana). Local rumor had it that Glanton always “raised the hair” of the Indians he killed and that he had a “mule load of these barbarous trophies, smoke-dried” in his hut even before he turned professional.

According to Chamberlain, John Glanton was born in South Carolina and migrated to Stephen Austin’s settlement in Texas. There he fell in love with an orphan girl and was prepared to marry her. One day while he was gone, Lipan warriors raided the area scalping the elderly and the children and kidnapping the women- including Glanton’s fiancee. Glanton and the other settlers pursued and slaughtered the natives, but during the battle the women were tomahawked and scalped. Legend has it, Glanton began a series of retaliatory raids which always yielded “fresh scalps.” When Texas fought for its independence from Mexico, Glanton fought with Col. Fannin, and was one of the few to escape the slaughter of that regiment at the hands of the Mexican Gen. Urrea- the man who would eventually employ Glanton as a scalp hunter. During the Range Wars, Glanton took no side but simply assassinated individuals who had crossed him. He was banished, to no avail, by Gen. Sam Houston and fought as a “free Ranger” in the war against Mexico. Following the war he took up the Urrea’s offer of $50 per Apache scalp (with a bonus of $1000 for the scalp of the Chief Santana). Local rumor had it that Glanton always “raised the hair” of the Indians he killed and that he had a “mule load of these barbarous trophies, smoke-dried” in his hut even before he turned professional.

It’s fascinating to note how much of the Judge is already there–the pedophilia, the marksmanship, the scholarship, and, most interesting of all, the lack of hair. Confession goes on to detail the killing, scalping, raping, and raiding spree that comprises the center of Blood Meridian. Chamberlain even describes the final battle with the Yumas, an event that signals the dissolution of the Glanton gang in McCarthy’s novel.

It’s fascinating to note how much of the Judge is already there–the pedophilia, the marksmanship, the scholarship, and, most interesting of all, the lack of hair. Confession goes on to detail the killing, scalping, raping, and raiding spree that comprises the center of Blood Meridian. Chamberlain even describes the final battle with the Yumas, an event that signals the dissolution of the Glanton gang in McCarthy’s novel.

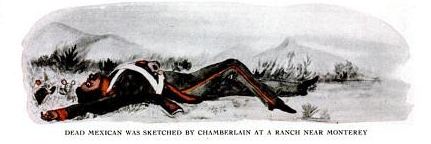

Content aside, Chamberlain’s prose also seems to presage McCarthy’s prose. In his book

Content aside, Chamberlain’s prose also seems to presage McCarthy’s prose. In his book  You can view many of Chamberlain’s paintings and read an edit of his Confession in three editions of Life magazine from 1956, digitally preserved thanks to Google Books–here’s

You can view many of Chamberlain’s paintings and read an edit of his Confession in three editions of Life magazine from 1956, digitally preserved thanks to Google Books–here’s