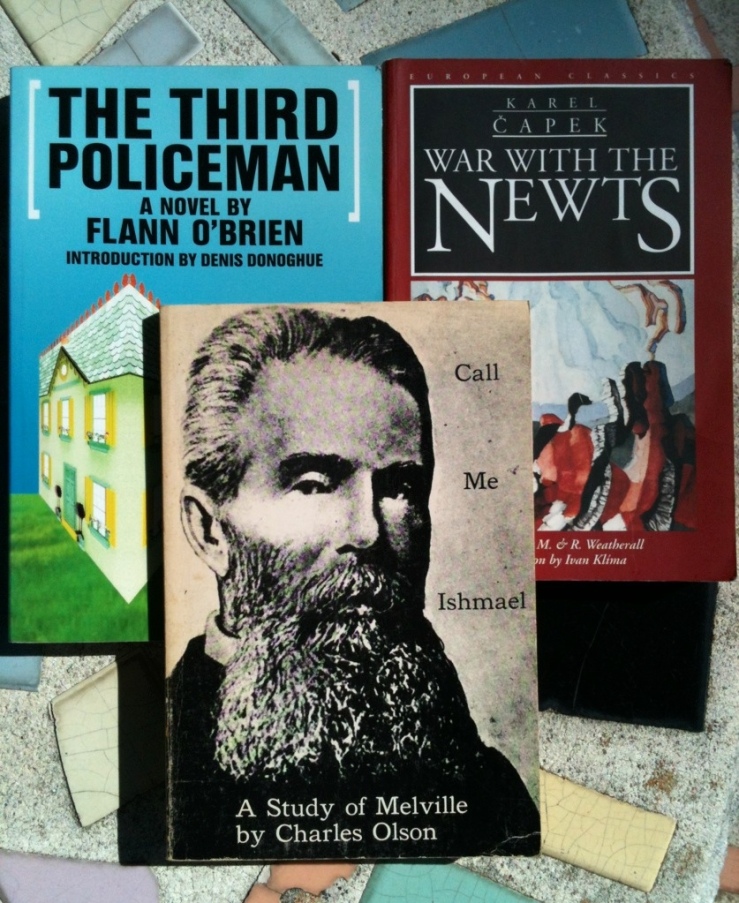

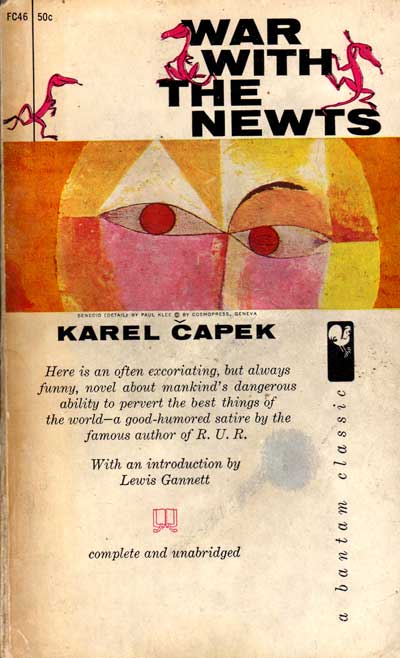

Even though the plot of War with the Newts may not shock audiences accustomed to its “human-invention-intended-for- good-becomes-in-the-end-not-so-good” story, readers shouldn’t neglect this often-overlooked science-fiction classic from 1937 by notable Czech writer and satirist Karel Capek. Humans, motivated by a range of impulses: greed, curiosity, and sometimes even the best of intentions, have created an uncontrollable menace and brought about the end to their dominion over the planet. Computers, robots, even monkeys have spelled doom for mankind, but Capek warned, in this short and sparkling book, that while masses of intelligent amphibians must be dealt with cautiously, true danger arises from our manipulation of the natural world, the unceasing capitalist drive to increase production by exploiting the weakest, and our inability to foresee the consequences of our actions.

The action begins when a drunk but benevolent sea captain discovers a new species of amphibians inhabiting the waters near an isolated island in the Pacific Ocean. These docile creatures are able to breathe on land, walk on their hind legs, and communicate using rudimentary sounds and gestures. The captain trains them to speak a pidgin English and dive for pearls before arming them so that they might fend off the sharks that prey on their young. Once he receives generous financial backing from a Dutch conglomerate, he ships them to similar islands where pearl harvests have been been impossible or unproductive. Eventually big business determines that the tireless and fecund newts are valuable for the expansion and development of economic activities near the coasts and under the seas and develop a global marketplace for trade in their labor and bodies. Educated, well-equipped, and trained to use with the most advanced technologies, the newts produce the greatest expansion of wealth in the history of the world before taking it all for themselves, returning the continents to the bottom of the ocean while requiring a small cadre of humans, relocated to the mountains, to produce the steel and weapons required to support their new Atlantis.

Written as a history book, Capek brilliantly footnotes his narrative with carefully crafted primary sources: newspaper reports, academic studies, religious tracts, political manifestos and corporate minutes in order to illustrate human reaction to new, unsettling circumstance. A nimble author blessed with the knowledge and skill to write comfortably about a wide variety of subjects, Capek captures both the progressive and cautious voices that shape human reaction to the slow advancement of a new and underestimated intelligence. He shows that agreement against economic interest is impossible; labor, for instance, bemoans loss of work to newt hordes while agriculture comes to rely on the millions of new mouths that have to be fed. Scholars measure, analyze, and categorize; anonymous tract-writers urge an uneasy populace to take up arms against sea-dwelling usurpers while the young and fashionable flock to newt cults, giving themselves up to sexual licentiousness they relish the mysterious and taboo.

But though Capek capably documents trivialities, most of his accounts reflect the time in which he lived and wrote, between the two great European wars, situated between Stalin’s Russia and Hitler’s new Germany, at the height of colonial exploitation, not yet separated by a century from the horrors of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and the American Civil War. In a report written by the “Salamander Syndicate,” the organization responsible for the organization and dissemination of the world trade in newts justifies the “humane” husbandry, categorization, and sale of newts according to their physical attributes. Exemplary newts are invited to join committees and expound on their visions for a future shared with humans. Echoes of American abolitionist thought appear in the debates waged in the media regarding the existence of newt art and culture, their assumed “soullessness,” and the minimal levels of education required for their lives as workers.

The newts, masters of human technology, eventually take over. Humans, fleeing to higher ground, are incapable of bringing the fight to the seas. War with the Newts is an indictment not only of our ability to take without question unearned economic value, but also of our inability to halt the mechanisms by which we accrue those benefits once it becomes evident that the process of enrichment, by itself, is detrimental to the common good. This is a very good book, a satire of the institutions that will fail when we need them the most, created by a writer whose demonstrated virtuosity deserves more attention.