The enemy of society on the run toward “freedom” is also the pariah in flight from his guilt, the guilt of that very flight; and new phantoms arise to haunt him at every step. American literature likes to pretend, of course, that its bugaboos are all finally jokes: the headless horseman a hoax, every manifestation of the supernatural capable of rational explanation on the last page—but we are never quite convinced. Huckleberry Finn, that euphoric boys’ book, begins with its protagonist holding off at gun point his father driven half mad by the D.T.’s and ends (after a lynching, a disinterment, and a series of violent deaths relieved by such humorous incidents as soaking a dog in kerosene and setting him on fire) with the revelation of that father’s sordid death. Nothing is spared; Pap, horrible enough in life, is found murdered brutally, abandoned to float down the river in a decaying house scrawled with obscenities. But it is all “humor,” of course, a last desperate attempt to convince us of the innocence of violence, the good clean fun of horror. Our literature as a whole at times seems a chamber of horrors disguised as an amusement park “fun house,” where we pay to play at terror, and are confronted in the innermost chamber with a series of inter-reflecting mirrors which present us with a thousand versions of our own face.

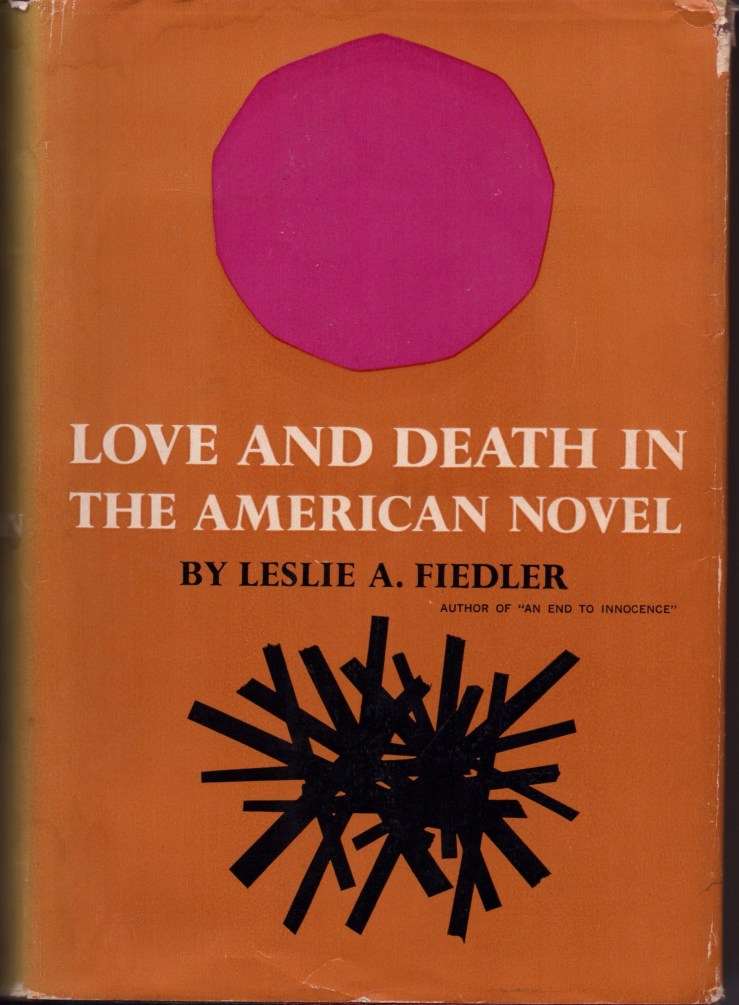

From the introduction to Leslie Fiedler’s Love and Death in the American Novel (1960).

Damn.

LikeLike

Jesus Christ, that person is illiterate.

If they think that Twain — or even Your Narrator, Huck — wishes to convince the reader that the intense (and contemporaneously v. controversial) violence of Huckleberry Finn is, at the end, a joke, they deserve to be bludgeoned to death by clowns. No one thinks that book is good clean fun; it is not intended to exonerate violence, but to condemn and excoriate its pervasiveness. The coercive violence of the South, of mankind, is mediated by Huck’s uneducated innocence, but only a complete moron would then go on attribute his blamelessness to the depictions of violence themselves. The reader is supposed to be appalled, not entertained. Twain shows us what he thinks of the Boys’ Own Adventurousness of Tom Sawyer in the novel’s final, perplexing act — he is a soulless monster who reenacts the offices of slavery, for fun & on an innocent person, because he likes how romantic the chains look. This is not a writer who mindless regurgitates action spectacles because he thinks they’re a rollicking good time.

Americans do love to pretend that violence is neither consequential nor a signifier of anything in particular (and also an awe-inspiring pretext for heteronormative male heroism), but bad move picking one of the only works of art in the canon that confounds the thesis.

This is equivalent to, but even stupider than, “because liberals are always calling out racism, that means they’re the real racists.” Holy shit.

(I don’t know if ‘Leslie Fielder’ is a sis or a bro, hence my use of the singular “they.”)

LikeLike

Fiedler died 15 years ago and is thus unavailable to be bludgeoned to death by clowns.

Plenty of critics thought of the book as good clean fun in the 1950s, and Fiedler is addressing them, essentially, using an ironic tone. Perhaps with more context the intention of his passage might have been clearer (and saved poor Fiedler from clown-death-wishes). Here he is a page or two later—

LikeLike