My third (complete) trip through James Joyce’s Ulysses finds me just as (or even more than) stunned as the previous two journeys, a bit (very much) unequal to properly reviewing the book, but this time with an easy out — I listened to an unabridged, full cast audio recording. The aforementioned “easy out” is resting on the received greatness and goodness (and evilness) of the book, which I will hardly contend with and heartily endorse (and do very little real critical work to support my endorsement). Ulysses is fantastic. But what about this audio recording?

My third (complete) trip through James Joyce’s Ulysses finds me just as (or even more than) stunned as the previous two journeys, a bit (very much) unequal to properly reviewing the book, but this time with an easy out — I listened to an unabridged, full cast audio recording. The aforementioned “easy out” is resting on the received greatness and goodness (and evilness) of the book, which I will hardly contend with and heartily endorse (and do very little real critical work to support my endorsement). Ulysses is fantastic. But what about this audio recording?

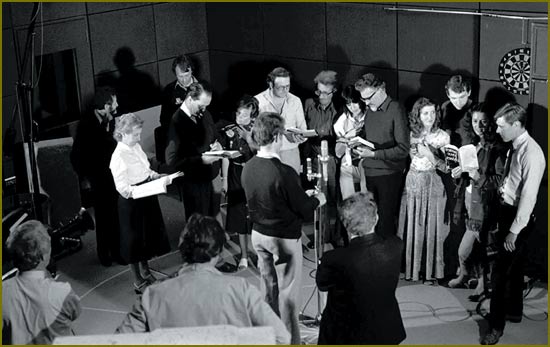

First thing’s first — I listened to, absorbed, choked up at, guffawed about, cackled around, and generally loved RTÉ’s 1982 dramatized, soundtracked, sound-effected, lovingly detailed recording of Ulysses, a work crammed with voices to match (if perhaps not equal) Joyce’s big fat work. This recording is not as widely available as LibriVox’s (free) full cast production or Jim Norton’s Naxos reading, but, after sampling both, I’d argue that it’s better. The Irish players bring sensitivity and humor to their roles, but beyond that pathos, the energy of RTÉ’s troupe is what really makes the book sing. Leopold Bloom gets his own voice, as does Stephen Dedalus and Molly (and all the characters). This innovation propels the narrative forward with dramatic power, and clarifies the oh-so indirectness of Joyce’s free indirect style, making the plot’s pitfalls and pratfalls more distinct and defined. There are songs (and dances) and music (and musing) and humming (and hemming and hawing and reverb). There is chanting and chawing and brouhaha. There is chaos and calamity and confusion. There is brilliance and peace and transcendence. It’s all very good, great, wonderful.

So: Who is a full cast unabridged audio recording of Ulysses for? Say, for instance, can someone who’s never read Ulysses listen to this instead?

I don’t know.

Here’s what I think though: Ulysses begs to be read aloud, is musical, soundical. Beyond obvious chapters like episode 11, “Sirens,” an overtly musical interlude that actually hurt my throat the first (second?) time I read it (even though I read it that time silently) — beyond the obvious musicality of “Sirens,” Ulysses hums and thrums and bristles and thumps with lively, vocal, melodious, rhythmic energy, pulses in sound and vision. The full cast reading, to cling to a hoary cliché, brings this sound and vision to life, animating Joyce’s words with a just vitality. But I’ve tripped into details, put carts before horses — the prime advantage for an audio recording of Ulysses to newbies is probably how clearly (and audibly, ahem) it delineates the book’s plot. But —

At the same time, I think anyone reading the book for the first time will want to read it along with the audio recording. Read along as in literally read along with, or, more likely read first or after — chapter by chapter that is. Yes, I think, yes, that’s what I’d recommend (lagersoaked now as my brain might be) — read a chapter first, then listen, then read another (or reread). Rinse. Lather. Repeat.

Now I retreat to that ugly bastard of literary criticism, reader response shtick, the stuff of fellows who can’t make real claims on the work itself but rather hide behind how the book made me feel and think and blah blah blah. Sorry. I break myself against Ulysses. And it’s not even the book, truth be told (to trot out another hoary cliché) — I’ve reviewed books here that sought to rival Ulysses, books that undoubtedly contend with it — it’s more the critical tradition that accompanies Ulysses that daunts me. But enough. Anyone who wishes to read pages of graduate school work on the subject, written by moi, may apply below. Suffice to say for now that I loved loved loved listening to this audio recording.

Perhaps because I was so familiar (or familiar enough) with Joyce’s themes at this reading/auditing, I was able to relax during this odyssey through Joyce’s epic. To put it another way, I felt no need to be “on” — to pick up allusions, to grasp at threads — and trip over them. Instead, I found a human dimension to Joyce’s work, one I’d felt there before, but perhaps not fully experienced (I am not claiming that I have fully experienced Ulysses). I laughed. I angered. I spit. I snarled. I cried (yes, I cried; at the mention of Rudy at the end of “Circes,” and then, again, at the end of the novel, just a bit, when I felt (felt) Molly’s love for her husband). There might have been a stirring at the loins.

I found a confirmation of my favorite episodes: “Circe,” foremost, an apocalyptic carnival brought to a bristling boil in the Irish cast’s capable choir. The aforementioned “Sirens” sings of course; far more pleasant, really, to hear than read. “Telemachus,” sure, who can nay-say an opener like that, although it’s really just the opener to the prelude to the real opener “Calypso” — great stuff. What earthy joy to meet Bloom. “Hades” — a sad treat. “Aeolus” — a funny treat, windily rebounding in vim and vigor and vigorous vim. The library episode — “Scylla and Charybdis” — I’ve always thought of it as Hamlet and Stephen, or grandfathers and ghosts — becomes clearer in the voices of RTÉ’s cast. Clearer not in the sense of: “Now I understand what Stephen’s getting at,” but clearer in the sense: “Now I see where Stephen sees what he is not quite sure he is getting at.” That chapter on pig-headed closemindedness, “The Cyclops” — a triumph, a magnitude, a bold chuckle. And “Penelope.” Well, yes, great stuff.

It’s more remarkable, I suppose, the ways in which RTÉ’s recording illuminated those chapters I’d struggled with, those that had made me yawn. The first, tedious, purposefully clichéd half of “Nausica” tried my patience (get back to Bloom!) — but the actress who reads it highlights the chapter’s tedium, its commonplaces — even as it/she rushes to that juicy climax. “Proteus”: far more manageable than I’d remembered. And “The Oxen of the Sun” (aka that chapter that I never really read properly) — well, with a full band of nasty drunken med students, a bold narrator (and a sympathetic nurse), this stumbling rock becomes a springboard to the madness I so love (and have loved) in “Circe.” In the once-trying catechism of “Ithaca,” the actors find a rhythmic bounce, a dry crunching that explodes in the wet gush of “Penelope.” And didn’t I say, yes, great stuff.

What this audio recording does best is humanize Joyce’s characters. While there is never a doubt that they are set against their mythotypical forebears, I found in Joyce’s characters this time a deep specificity, a concreteness of place, a realness. I found no need to situate a Bloom-as-Odysseus correspondence. Molly did not have to be an earth goddess. Stephen was freed from the burden of Hamlet. Sure, metempsychosis was in play, but it was a backdrop, not a foregrounding, determining analytical program. I think the audio recording helped transmit this humanity, a humanity that was always there, obscured by the clutter of critical tradition.

If I haven’t been clear: Very highly recommended.