Yann Martel’s Beatrice and Virgil tells the story of a writer named Henry whose follow-up novel to a surprise smash hit is rejected. He moves to a large metropolitan city, gets a dog and a cat, takes clarinet lessons, joins an amateur theater group, and slowly forgets about writing fiction altogether. One day a stranger sends Henry a short story by Gustave Flaubert called “St. Julian the Hospitator.” The sender has highlighted passages about Julian’s delight in slaughtering animals and also included a few pages of an original manuscript, a Beckettian play featuring two characters, Beatrice and Virgil. There’s also a note asking for help. Intrigued, or maybe bored, Henry visits the mysterious author, an old, creepy taxidermist (also named Henry). His play features two characters, Virgil, a howler monkey, and Beatrice, a donkey, who are trying to come to terms with a series of events they call The Horrors. The taxidermist’s project reignites Henry’s passion for writing and he’s soon helping the would-be playwright with revisions, blind to the inconsistencies and gaps in the old man’s strange behavior.

Beatrice and Virgil is a page turner, engaging, propulsive, and quite easy to read. It injects the philosophical and artistic concerns of literary fiction into the frame and pacing of a book designed for broader audiences. Martel displays his keenest literary skill in the early part of the novel, flitting through the kinds of subjects that bookish nerds of a certain postmodernist bent tend to obsess over: the possibilities and challenges of writing in a particular language, the complexity of pseudonymous fame, the intellectual allure of the essay versus the power of fiction to narrativize higher truth. To address this latter problem, Henry proposes that his new book comprise two sections–a work of narrative fiction and an essay to explicate that work. Why the need for an essay? Henry proposes to write an artful, fictive account of the Holocaust. The essay, which Henry wants published on the flip side of the fiction, thus eliminating a front/back cover distinction, is meant to explicate the fiction. In many ways the first section of Beatrice and Virgil functions as counterpoint to Henry’s proposed essay, concisely addressing the problems of using anything other than historical facts to represent the Holocaust.

After Henry gets the taxidermist’s package and reads “St. Julian the Hospitator,”Beatrice and Virgil moves into a faster rhythm and continues to accelerate to its end, never sagging. At times, Martel relies on stock phrasing and overt exposition to afford this pacing. I found myself wishing a few times that he would trust his audience a bit more. Is it really necessary to directly explain the titular allusion to Dante’s Divine Comedy? He could also be a bit less free with his narrator’s everyman style of questioning, a device employed often to propel the plot, but one somewhat inconsistent with Henry’s obvious intellectual acumen. Martel’s occasional use of lazy devices of the Dan Brown school directly contrasts the more experimental or postmodern aspects of his book. There’s the book’s initial section, which reads very much like a lyric essay; there’s the exegesis of “St. Julian”; there’s the taxidermist’s play, Beatrice and Virgil; there’s the book’s final section, “Games for Gustav.” This final section comprises thirteen short epigrams written in second-person perspective. “Games for Gustav,” Henry’s Holocaust art, demands audience identification with the victims of the Holocaust. Its brevity and ambiguity correlate to the narrative’s ahistorical engagement with the Holocaust and communicate a sense of apprehension and distance toward the subject. Is that subject Martel’s or Henry’s? In a piece I wrote last month about Beatrice and Virgil and the challenges of an aesthetic response to the Holocaust, I suggested that “Henry, a young French Canadian with no Jewish roots is utterly divorced from any authentic response to the Holocaust. He could write an academic essay on the subject, or a navel-gazing bit of metafiction that dithered over storytelling itself, but he essentially already has an answer to his own question of why there are so few artistic responses to the Holocaust–that to re-imagine or re-interpret or otherwise re-frame the real events of the Holocaust in art is to, at once, open oneself to dramatic possibilities of failure.”

Is Beatrice and Virgil an authentic response to the Holocaust? I won’t accuse Martel of using the Holocaust as a mere prop in his novel; indeed, anticipation of such an accusation is precisely what leads Henry to suffer over an essay to explicate his fiction. Martel’s book is about murder, horror, and how one might witness to or otherwise narrativize murder and horror; Henry’s “Games for Gustav” is just one of those attempts to witness. The novel engenders multiple readings then. We can take Henry’s “Games” as part and parcel of Martel’s program, read them perhaps as Martel’s own attempt at poetry after Auschwitz. This reading would subscribe to a traditional narrative arc–Henry faces a challenge, endures a perilous task, and finds resolution in his art: a valid artistic response to the Holocaust is possible. I think, however, that there is another, more complicated reading available, one far more ambiguous, one that places any aesthetic response to the Holocaust under suspicion. If we scrutinize the elements of traditional narrative fiction at work in the novel, we can see multiple ironies in Henry’s “hero arc,” ironies outside of Henry’s otherwise perspicacious gaze. To write an authentic aesthetic response to the Holocaust, Henry must face some kind of deathly extreme that will license such art. But is such a licensing, a conferring of authority possible? I won’t point to spoilers here but will say that I read the novel’s climax ironically. I believe it complicates Henry’s (and perhaps Martel’s) attempt to engage the Holocaust via metaphor and artifice and calls the novel’s resolution into question.

But these matters are probably better reserved for the detailed dialogues the book will no doubt inspire. Beatrice and Virgil raises essential questions of post-postmodernity, exploring the porous boundaries between autobiography and fiction, history and myth, and the limits of allegory. Its rewards are not in its answers but in its questions.

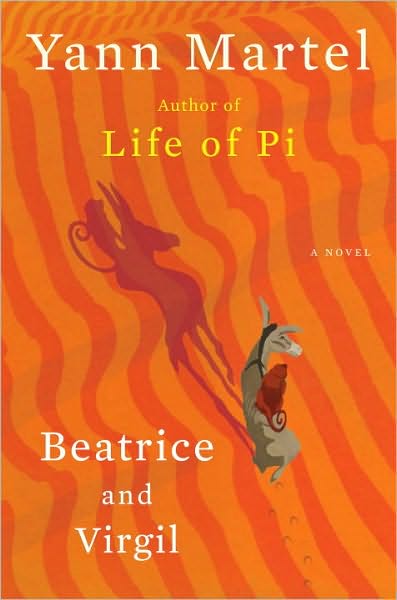

Beatrice and Virgil is new in hardback from Spiegel & Grau on April 13, 2010.

Well written review! Thanks for this.

LikeLike

[…] Yann Martel Talks About His New Novel, Beatrice and Virgil Posted in Books, Literature, Writers by Biblioklept on April 12, 2010 Yann Martel talks about autobiography, animals, and more in his new novel Beatrice and Virgil. […]

LikeLike

Really fantastic review, Biblopklept. The best I’ve read on Beatrice and Virgil and the only one to question how that ending should be read. Never visited this site before but will have to check your other reviews now.

LikeLike

[…] https://biblioklept.org/2010/04/11/beatrice-and-virgil-yann-martel/ […]

LikeLike