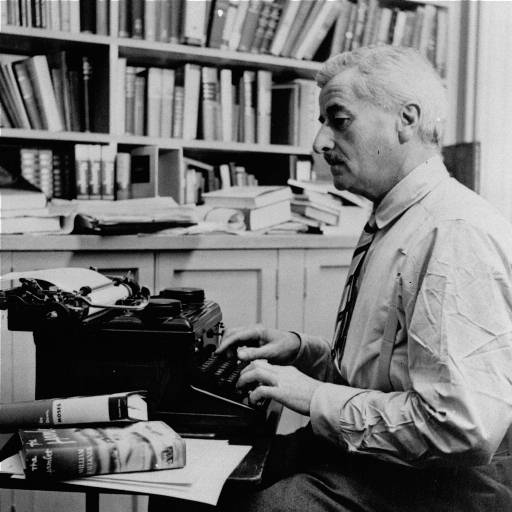

Not quite two years ago, I wrote some pretty awful things about William Faulkner on this blog. In a review of his first published novel Sancutary, I argued, quite ineffectually, that, “Faulkner as an American Great is nothing but a scam.” Elsewhere, I proffered this ignorant nugget:

“…it seems that a few critics–notably Malcolm Cowley and Cleanth Brooks–decided either that a. Faulkner is really great and/or b. America needs a new master of literary fiction, and it might as well be Faulkner. It seems amazing to me that these two critics conned a whole generation into believing that someone whose books were so unbelievably poorly written was actually, like, a totally awesome and important writer.”

Ouch. At the time I wrote that rant, I was still in grad school, which is to say I was still being assigned reading by well-intentioned professors. I was also laboring under a cruel miscalculation, the mistaken belief that I had actually read most of Faulkner’s great works–As I Lay Dying, The Sound and the Fury, and Absalom, Absalom!–in my high school and undergraduate courses–where said books were assigned reading. The truth, I realize now, is that while Faulkner’s strange, dense, elliptical prose might have passed under my eyes, I completely failed to read his books when I was a young man. It wasn’t until last spring, when I read one of Faulkner’s last novels, Go Down, Moses, that I came to understand the genius of his writing, which is to say I came to learn to read his voices in a non-academic, non-studied fashion, intuitively and rhythmically. Go Down, Moses is strange and sad and funny and truly an achievement, a book that works as a sort of time machine, an attempt to undo or recover the racial and familial (in Faulkner, these are the same) divides of the past.

So. Skip ahead a year.

After reading Bolaño’s stunning 2666, I strategically read Cormac McCarthy’s Child of God, knowing that I’d need a voice at least equal to Bolaño’s in order to not get totally bummed out and sort of paralyzed with that “What do I read next?” feeling. The strategy worked, but of course I needed a follow up book. So I picked up As I Lay Dying, the story of a poor rural family who labor to return their dead matriarch to her family’s home town for burial. I’d “read” the book in high school; I remembered the plot, but I could not in any way comment on it. This time, with the freedom to choose to read it–and perhaps, older, better equipped–I truly entered the book, entered into each of the character’s heads, their eyes, their voices. I “got” it.

I read As I Lay Dying in essentially three or four long sittings, sustained by Faulkner’s incomparable, engrossing language. I realize now that as a high school student, and then again as an undergrad, I resisted the book, attempted to impose my own consciousness into the narrative in order to “understand” the plot, rather than letting the book happen to me–which I believe is how one must read Faulkner. I was amazed how quickly I read the book once I attuned myself to Faulkner’s rhythm, and I was equally amazed at how conflicted and confused I felt about the story. I can’t recall a novel whose characters I’ve ever felt so hateful and sympathetic toward at the same time. Great, great book.

Anyway. The point of this post is to say, “Hey, I was wrong, mistaken, terribly wrong about Faulkner when I said he wasn’t a Great American Writer.” I suppose I’m also implicitly arguing that the necessary evil of assigned reading can sometimes be less necessary and more evil: How many kids are we turning away from the really great stuff forever by forcing it upon them when they are too young, too unequipped to appreciate it? The other side of this logic, of course, is to point out that often assigned reading can turn us on to great writers forever; this was the case for me, with most of what I read in high school. Still, as an English teacher I do worry that in assigning and then dissecting literature–under the pretense of explaining it and appreciating it and learning from it–we always run the risk of killing it, draining it of the very vitality that was the rationale for reading it in the first place. Of course, there’s a simple, simple antidote to reconciling yourself to all those books you hated in high school, those books you were supposed to love and be moved by and learn important and meaningful lessons from–you can read them again for the first time. The worst that could happen is a confirmation of your own prejudice; far more likely, in assigning your own reading, you’ll find something truly great and meaningful.

well there’s a change of heart i’m glad to see. I can’t wait to read AILD…it’s a few books down the list (i read four Faulkner novels in a row before deciding to take time to read other stuff) but i’ll definitely read it this year. i absolutely agree about required reading…i think there’s a thin line between overstepping the boundaries of adolescent understanding and failing to properly educate and culture, but when i think back to the novels i read in high school as assigned reading – i highly question my lasting impressions of them. i wonder if i would now enjoy those that i labored through then, and if i would find the ones i enjoyed to be less enjoyable now. in any case – glad you’re in the faulkner camp now, and i would highly recommend re-reading The Sound and The Fury as it’s a top 10 favorite all-time for me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My first Faulkner was The Sound and the Fury just after I finished college. It was probably the second non-assigned novel I read after leaving studenthood behind. I’m not sure how much of it I actually got, but I was still totally enamored of the freedom of being able to simply read without attempting to relate what I was reading to whatever theory or criticism I was being forced to read alongside it, or trying to fit it into some framework for a paper. Anyway, I enjoyed it enough to lead me to pick up a used copy of Absalom, Absalom a couple of years later. Again, I’m not sure how much of it I consciously understood, but I remember feeling like the language was swirling around me, sometimes settling, and often offering stark, bracing repeated images almost like sign posts to help me feel me at least somewhat grounded. It would probably rank among my top 5 or 10 reading experiences. I read As I Lay Dying a couple of years ago. Where Absalom felt grandiose and menacing, I remember feeling that As I Lay Dying was far more restrained and left each character dignified within his/her own self-absorbed alienation. That’s what comes back to me now anyway. I’d be curious to know how accurate that memory actually is. I see a re-reading in the near future.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the comments, Mike and supereg (sidebar: Mike: where’ve you been? Is Picklebilly dead? Too much brine?) So. I read the first part of TSatF, Benjy’s part–titular idiot, i suppose–this weekend and last (two 35 page sittings, basically). Because I did both BA and MA in English, I knew the plot beforehand (as I mentioned I’d “read” the book before). It is only because I know the plot that I “get” what is going on. I can’t imagine the first person to read this book…like, not F’s editor, just some dude. How would they be equipped? How could a high school kid–a kid!–get through it?! In any case, it is genius, no doubt, but is that only b/c I know enough of what the book *is* to parse meaning from Benjy’s idiocy?

LikeLike

i am happy to know that it really takes a person’s mature literary instincts to evaluate the real merit of a phenomenal writer like Faulkner. being a person interested in his fiction it really provides an impetus to acknowledge the greatness of his illuminated self.

LikeLike

[…] Faulkner on this blog, suggesting that he was the most overrated American writer of all time. I took it all back, of course, and now would rate Light in August and Go Down, Moses as two of my favorite books. I […]

LikeLike

[…] tea. think about one of the biggest park graveyards next to the lake and of having left the book AS I LAY DYING in the Phils without having read […]

LikeLike

Like I always tell my English students, “Read it twice to read it once.” Read it for pleasure the first time to gain a sense of the flow and the plot (letting the book happen to you), then go back and dissect the second time you read it. It is important to give the youth challenging classics. The conflicts involved in the classics transcend space and time, making the material equally useful to an 18 or 80 year old. Hooking these modern, technologically-determined, texters into a seemingly boring, timely text promotes its own problems. FRONTLOADING is key. Just like the first sentence of an essay can make or break an A-paper, your first sentence about the novel can do the same. Bring it to thier level and let them tell you!

LikeLike

I love Faulkner and am really enjoying your blog this morning. That’s all I’ll take the time to say, because, “STOP, Rosalie. This is what you do, just go from one pleasantry to another, and not getting done what you’d intended to do!” “Is that a bad trait?” I answer.

LikeLike