One of the many small vignettes that comprise Jerzy Kosinski’s 1968 book Steps begins with the narrator going to a zoo to see an octopus that is slowly killing itself by consuming its own tentacles. The piece ends with the same narrator discovering that a woman he’s picked up off the street is actually a man. In between, he experiences sexual frustration with a rich married woman. The piece is less than three pages long.

There’s force and vitality and horror in Steps, all compressed into lucid, compact little scenes. In terms of plot, some scenes connect to others, while most don’t. The book is unified by its themes of repression and alienation, its economy of rhythm, and, most especially, the consistent tone of its narrator. In the end, it doesn’t matter if it’s the same man relating all of these strange experiences because the way he relates them links them and enlarges them. At a remove, Steps is probably about a Polish man’s difficulties under the harsh Soviet regime at home played against his experiences as a new immigrant to the United States and its bizarre codes of capitalism. But this summary is pale against the sinister light of Kosinski’s prose. Consider the vignette at the top of the review, which begins with an autophagous octopus and ends with a transvestite. In the world of Steps, these are not wacky or even grotesque details, trotted out for ironic bemusement; no, they’re grim bits of sadness and horror. At the outset of another vignette, a man is pinned down while his girlfriend is gang-raped. In time he begins to resent her, and then to treat her as an object–literally–forcing other objects upon her. The vignette ends at a drunken party with the girlfriend carried away by a half dozen party guests who will likely ravage her. The narrator simply leaves. Another scene illuminates the mind of an architect who designed concentration camps. “Rats have to be removed,” one speaker says to another. “Rats aren’t murdered–we get rid of them; or, to use a better word, they are eliminated; this act of elimination is empty of all meaning. There’s no ritual in it, no symbolism. That’s why in the concentration camps my friend designed, the victim never remained individuals; they became as identical as rats. They existed only to be killed.” In another vignette, a man discovers a woman locked in a metal cage inside a barn. He alerts the authorities, but only after a sinister thought — “It occurred to me that we were alone in the barn and that she was totally defenseless. . . . I thought there was something very tempting in this situation, where one could become completely oneself with another human being.” But the woman in the cage is insane; she can’t acknowledge the absolute identification that the narrator desires. These scenes of violence, control, power, and alienation repeat throughout Steps, all underpinned by the narrator’s extreme wish to connect and communicate with another. Even when he’s asphyxiating butterflies or throwing bottles at an old man, he wishes for some attainment of beauty, some conjunction of human understanding–even if its coded in fear and pain.

In his New York Times review of Steps, Hugh Kenner rightly compared it to Céline and Kafka. It’s not just the isolation and anxiety, but also the concrete prose, the lucidity of narrative, the cohesion of what should be utterly surreal into grim reality. And there’s the humor too–shocking at times, usually mean, proof of humanity, but also at the expense of humanity. David Foster Wallace also compared Steps to Kafka in his semi-famous write-up for Salon, “Five direly underappreciated U.S. novels > 1960.” Here’s Wallace: “Steps gets called a novel but it is really a collection of unbelievably creepy little allegorical tableaux done in a terse elegant voice that’s like nothing else anywhere ever. Only Kafka’s fragments get anywhere close to where Kosinski goes in this book, which is better than everything else he ever did combined.” Where Kosinski goes in this book, of course, is not for everyone. There’s no obvious moral or aesthetic instruction here; no conventional plot; no character arcs to behold–not even character names, for that matter. Even the rewards of Steps are likely to be couched in what we generally regard as negative language: the book is disturbing, upsetting, shocking. But isn’t that why we read? To be moved, to have our patterns disrupted–fried even? Steps goes to places that many will not wish to venture, but that’s their loss. Very highly recommended.

I’ve read parts of steps. I think I put it down on purpose after the gang rape scene.

I’ve recommended The Painted Bird to you at some point, and that novel is another example of Kosinski’s take on the mundane horrors of everyday life. Basic plot summary: 10-year old Slavic-looking kid is abandoned by his parents in Nazi-occupied Russian. As he struggles to survive, he encounters people that either harm him or tolerate him. I read it in about 2 days.

Kosinski’s writing is so straightforward. As a reader, I just take it for granted that he’s telling me the truth. I think that when you feel that someone is simply reporting what has happened, they can to delve into such dark subject matter.

LikeLike

you mention the “truth” of his writing–steps seems awfully, darkly real to me. i’m sure you’ve read the attacks on the painted bird; the claims that it isn’t true and that it wasn’t initially composed in english (paul auster claims to have been one of the revisers)–do you think that matters?

LikeLike

Noquar, I think you should get more infomation about a book before you make any statements! first of all, the boy in the Painted Bird was not 10 but about 6. He was not of Slavic looks for that would not have been any problem for the locals, he was of Gypsy or Jewish looks, as it is described in the novel. Moreover, he was not abandoned in Nazi-occupied Russia, but somewhere in the Eastern Europe. Since he was Polish (as I am myself) it was assumed more probable that he was left somewhere in Poland. But anyway that does not really matter for it is proved that the whole book is a fiction!! No grain of turth! except for some autobiographcial inspirations, such as war itself, or some people and strange madical practises. I recommend you to read Black Bird by Joanna Siedlecka, who bothered to go to the village where young Kosinski (or rather Jerzy Lewinkopf) was raised by his parents. Siedlecka provides her reader with a reliable account of Kosinski’s childhood, basing her account on the coverages of the poeple who knew him as a child.

good luck,

Ola :)

LikeLike

I had no idea that there was controversy surrounding his authorship of the book, and I just sort of assumed that the account was fictional. After a quick perusal of Wikipedia, I’m of the opinion that none of that stuff really matters.

A bookseller near NYU had The Painted Bird priced at $1.00, and the critical blurbs on the cover sold me. The writing was phenomenal, and I was deeply moved by the book on any number of occasions. I ran into a friend on the subway as I reached the last page and implored him to take it from me; I thought it was that good.

I still remember that James Frey Oprah controversy from a few years ago, and my stance on that controversy hasn’t changed. If the writing is compelling, the actions taken by the writer to sell the book shouldn’t take away from what’s actually printed on the page.

LikeLike

[…] Kosinski talks to The Paris Review (1972). Read our review of his weird novel Steps. From the interview— […]

LikeLike

[…] Steps is an odd duck even for this list, because I’m not even sure if it’s ever been identified within a genre by any large group of readers. From my review: […]

LikeLike

I’m amazed I didn’t comment when you first posted this. I’m reading Steps for like the third time right now and I am just constantly blown away by it.

LikeLike

i’m searching for a short story by kozinski about a young man who has ibs, and shits his pants on the front porch of the girl he has finally summoned enough nerve to ask out.

LikeLike

i don’t recall that happening in Steps.

LikeLike

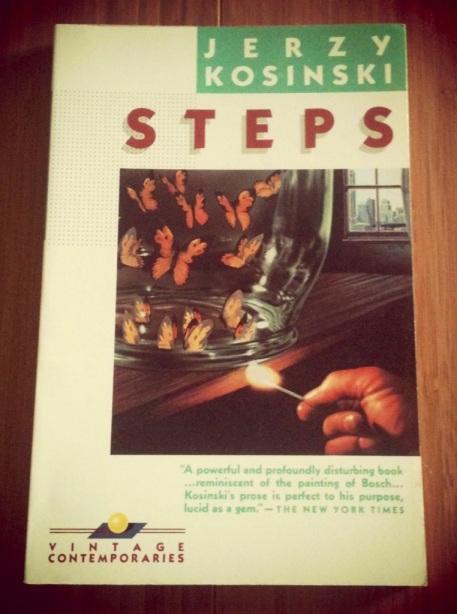

[…] the cover for Jerzy Kosinski’s twisted horrorshow-in-vignettes Steps is remarkably literal—sure, the image seems surreal, but it’s straight out of […]

LikeLike

[…] I reviewed Steps here. […]

LikeLike