Roald Dahl’s 1982 children’s classic The BFG begins with a dedication to the author’s daughter: “For Olivia: 20th April 1955 — 17th November 1962.”

If I had noticed the dedication when I first read The BFG as a child, I certainly didn’t think about it then. The slim sad range of those dates would have meant nothing to me, eager as I was to dig into a book about child-eating giants, secure in my own childish immortality. However, when I started reading the book with my daughter, the dedication howled out to me, thoroughly coloring the lens through which I read.

Had Olivia Twenty Dahl not died from measles encephalitis at only seven, had she continued to live to be alive now, she would be approaching her sixtieth birthday. But because she died as a seven-year-old little girl, she remained a seven-year-old little girl to me, the reader, who saw her spirit under every page.

I believe she remained a seven-year-old little girl for Dahl as well—at least in the imaginative world of The BFG where she is recast as the hero Sophie. Reading The BFG, it was impossible for me not to immediately connect Sophie to Olivia, those names with their Greek roots and their long O‘s. It was also impossible for me not to connect these two girls to my own daughter Zoe, who is also seven.

(Parenthetically, I’ll admit that biographical interpretation of literature is often a terrible practice—especially when combined with a touch of reader-response criticism—and that what I am doing here is not something I think advisable, let alone commendable. And yet the central affective power for me in reading The BFG—as an adult to my little girl—rests in my inescapable intuition that Dahl wrote the book to make his daughter live again, to live forever).

The BFG does not have an especially complex plot: Young Sophie, up late at night, is snatched away to a strange country by a giant whom she spies blowing dreams into a room of sleeping children (she does not of course know at the time that he is blowing dreams into the room). Luckily, this is the Big Friendly Giant. Unluckily, she’s stuck in his cave, where he must hide her from nine awful giants (including the Fleshlumpeater, the Meatdripper, and the aptly named Childchewer), who set off into the world each night to guzzle “human beans” (they especially love to eat children). The BFG, smaller than the other giants, refuses to partake in their infanticidal, anthropophagic practices, dining instead on stinky snozzcumbers. While the other giants are out gobbling up humans, the BFG is in Dream Country collecting dream blobs, which he mixes into wonderful visions and blows into children’s homes at night. Sophie and the BFG concoct a special dream for the Queen of England and through this scheme manage to capture the nine terrible giants. Sophie and The BFG live happily ever after.

Dahl’s command of language in The BFG marks the book as one of his strongest achievements. The most obvious and endearing aspect of the book’s language is the voice of the BFG, who invents, inverts, and generally twists up nouns, verbs, and adjectives into a fine mess. He tells Sophie:

Words . . . is oh such a twitch-tickling problem to me all my life. So you must simply try to be patient and stop squibbling. As I am telling you before, I know exactly what words I am wanting to say, but somehow or other they is always getting squiff-squiddled around.

That squiff-squiddling though is what gives the giant’s voice such power. The tinges of nonsense actually reify and amplify what the BFG intends to say. There’s a sing-songy, burbling, bubbling rhythm to the BFG’s speech, which I took great joy in performing aloud for my daughter. Dahl clearly understood that his prose would be read aloud.

The BFG’s trouble with “correct” language derives from the fact that he never got to go to school. In fact, he’s learned everything he knows from one book: Nicholas Nickleby, “By Dahl’s Chickens,” the BFG tells Sophie. The underlying problem that governs the plot of Nicholas Nickleby is the unexpected death of Nicholas’s father. Dahl might have picked any of Charles Dickens’s novels here, but I believe he chose this one to thematically answer to The BFG’s secret plot: A missing father to match a missing daughter.

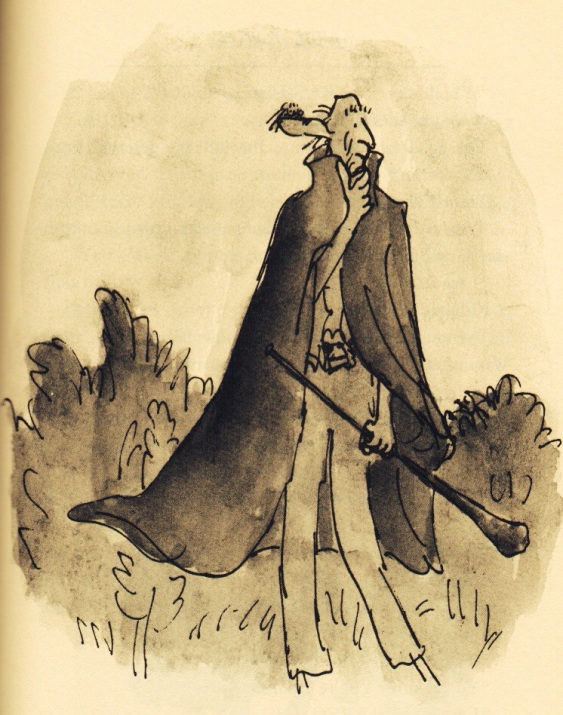

Dahl also not-so-subtly inserts his own name into the authorial position in this scene, which occurs about half way into the novel. This insertion happens again in the novel’s final chapter, which is appropriately titled “Author.” The book ends with the nine awful giants captured and held in a pit deep in the earth (shades of the Titans), their infanticidal violence contained and suspended, but still alive, still potential. The Queen has an enormous house built for the BFG right by her own palace, with a small cottage for Sophie in-between. The vision, rendered in Quentin Blake’s marvelous wobbly inks, suggests a fairy tale ending, as Sophie finds an ersatz family in the Queen (more of a fairy godmother) and the BFG, her new father.

And yet Sophie too takes on something of a parental role, teaching the BFG to read and write. He soon “started to write essays about his own past life.” Sophie reads these and urges him to become “a real writer … Why don’t you start by writing a book about you and me?”

Reading this chapter the other night devastated me and delighted my daughter. She cackled in glee and I found myself unable to perform the BFG’s voice through my tears. I finished the novel in my own, regular voice, doing my best not to let the sharp cracks of the emotion I felt break into those final lines, where we learn that the BFG, too modest to put his own name on his book (published by the Queen to bring joy to children), has chosen a pseudonym—the one on the spine of the book, Roald Dahl.

The BFG was of course always an author, even before he was literate; his medium was the dream, and he used dreams to tell stories to bring joy to children. He gave these dreams as protest, resistance, and counterattack to the consuming violence of his nine awful brothers.

Dahl’s rhetorical trick at the end of The BFG—claiming his own name as the pseudonym for the book’s real author, the Big Friendly Giant—is far less whimsical than a surface glance suggests. Rather, I find in it something sad, dark, and sincere, a moment of deep love and deep pain. The transposition—the squiff-squiddling, if you will—of the two names signals Dahl’s recasting of himself as the eternal BFG, bringing joy to children all over the world. The BFG gets to live happily ever after with his dream-daughter Sophie (the recast Olivia), their home and family sanctioned and provided for by the land’s highest authority.

But even before the Queen grants the father-daughter pair their own homestead, Sophie has already found her place by the giant—behind his ear, where she whispers to him. Is this not the fantasy of a consciousness that communicates beyond time, beyond death, directly and without the intermediary of a physical body?

Did Dahl hear Olivia’s voice in his own ear decades after her death? Did her spirit speak to him? Speculation of that sort is not my place or intention, and as I type it out, the suggestion appears far more lurid than I wish. I do know that the image was inescapable for me as I finished The BFG with my own daughter.

Our love and care for our children is shaded and intensified by an understanding of their fragility, their mortality, their susceptibility to disease, accident, chaos, the carelessness of others…factors easily metaphorized into child-eating giants. Our love for our own children precludes an equal love for children who are not our own, despite whatever ethical systems we claim to practice and subscribe to.

And this is what I find so moving about The BFG: Dahl converts the personal (and infinite) loss of his own daughter into a loving gift he seeks to share with all children. He shared that gift with me when I was a child, when I never imagined that I would grow up to be an adult with a child of my own to whom I would read that gift again, in a new, strange, sad, dark, joyous way.

Maybe all I am trying to say here, in this long, long-winded way, is Thank you.

For what it’s worth, I think the dedication to his daughter and the main character’s similarities to her are enough evidence for your moving interpretation.

LikeLike

I’ve seen the film but never actually read The BFG so had no idea all this existed – so thank you for that. And what a beautifully written piece.

LikeLike

Moving review about a touching story. Good deed.

LikeLike

I never made the connection when I was a child, but your analysis made be travel be in time, and into a strangely peaceful sadness.

Thank you for your excellent article. And your excellent blog overall.

LikeLike

This has been one of my all time favorite books and Dahl has been one of my favorite children’s authors. Thank you for sharing your insights. Several years ago I visited Great Missendon, Dahl’s hometown. The Dahl story center and museum is there. As I read your piece I remembered visiting his grave site, and as I read envisioning the BFG’s footprints that are there at his grave. Thanks again for your thoughts.

LikeLike

That’s why I have some children’s books so close to my heart

LikeLike

So beautiful, it almost has me crying.

I haven’t read this book, but my dad did read other Dahl’s when i was little. It’s so moving to think that was the voice of a father who had lost a child, it breaks my heart, because, somehow, in a winding way too, as a child i felt the love on those books just as if they were written for me. So… somehow… maybe a part of Olivia, the children part of Olivia, did live in every one of us, and that fatherly love he gave to us reached her too. I think this mysterious feelings are ok and beautiful to have from time to time.

I’m so glad i know this story now. I’ll have to get this book, hope it’s well translated to spanish!

LikeLike

[…] The BFG, Roald Dahl […]

LikeLike

[…] Dahl died of measles encephalitis, aged seven. The author went on to dedicate one of his most famous books to her, the BFG: “For Olivia: 20th April 1955 — 17th November […]

LikeLike

[…] Dahl died of measles encephalitis, aged seven. The author went on to dedicate one of his most famous books to her, the BFG: “For Olivia: 20th April 1955 — 17th November […]

LikeLike

[…] Dahl died of measles encephalitis, aged seven. The author went on to dedicate one of his most famous books to her, the BFG: “For Olivia: 20th April 1955 — 17th November […]

LikeLike

[…] Dahl died of measles encephalitis, aged seven. The author went on to dedicate one of his most famous books to her, the BFG: “For Olivia: 20th April 1955 — 17th November […]

LikeLike

Can’t wait movie! :)

LikeLike