At Penguin Classics on Air, David Simon explains how Stanley Kubrick’s film Paths of Glory—and the Humphrey Cobb novel it was based on–influenced his epic crime drama The Wire. (Via).

Vodpod videos no longer available.

At Penguin Classics on Air, David Simon explains how Stanley Kubrick’s film Paths of Glory—and the Humphrey Cobb novel it was based on–influenced his epic crime drama The Wire. (Via).

Vodpod videos no longer available.

Earlier this week, I pulled out From Hell with the bold intention of re-reviewing it for this site. I love Halloween and I love Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s epic revision of the Jack the Ripper murders, so this seemed as good an occasion as any for a reread (especially considering the “review” I wrote back in October of 2006 is so lazy that I won’t even link to it). Alas, I misjudged or misremembered the sheer density of From Hell–so, on Halloween day, I’m still only half way through, despite staying up way past my bed time, crouching under my sheets with a quavering flashlight, scanning Moore’s erudite words and Campbell’s scratchy inks (okay, that image is an exaggeration). I’ve read it at least thrice before, so I’ll review it anyway.

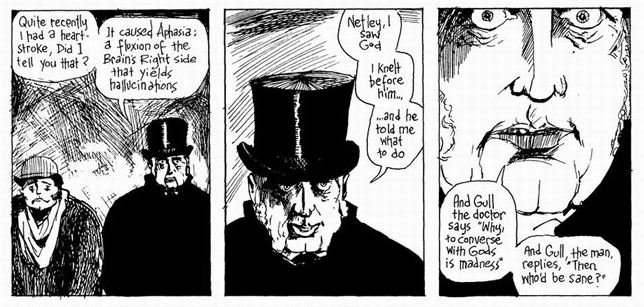

From Hell posits Sir William Gull, a physician to Queen Victoria, as the orchestrator of the Jack the Ripper murders that terrified Londoners at the end of the 19th century. Although the murders initially arise out of the need to cover up the knowledge of the existence of an illegitimate son begat by foolish Prince Albert, Victoria’s grandson. However, for Gull the murders represent much more–they are part of the continued forces of “masculine rationality” that will constrain “lunar female power.” Gull is a high-level Mason; during a stroke, he experiences a vision of the Masonic god Jahbulon, one which prompts him to his “great work”–namely, the murders that will reify masculine dominance.

One of the standout chapters in the book is Gull’s tour of London, with his hapless (and witless) sidekick Netley. In a trip that weds geography, religion, politics, and mythology, Gull riffs on a barbaric, hermetic history of London, revealing the gritty city as an ongoing site of conflict between paganism and orthodoxy, artistic lunacy and scientific rationality, female and male, left brain and right brain. The tour ends with a plan to commit the first murder. From there, the book picks up the story of Frederick Abberline, the Scotland Yard inspector charged with solving the murders. Of course, the murders are unsolvable, as the hierarchy of London–from the Queen down to the head of police–are well aware of who the (government-commissioned) murderer is. The police procedural aspects of the plot are fascinating and offer a balanced contrast with Gull’s mystical visions–visions that culminate in a climax of a sort of time-travel, in which Gull not only sees London at the end of the twentieth century, but also receives a guarantee that his murder plot has had its intended effect. From Hell takes many of its cues from the idea that history is shaped not by random events, but rather by tragic conspiracies that force people to willingly give up freedom to a “rational” authority. The book points repeatedly to the 1811 Ratcliffe Highway murders, which led directly to the world’s first modern police force. In our own time, if we’re open to conspiracy theories, we might find the same pattern in the 21st century responses to terrorism (Patriot Act, anyone?).

Although From Hell features moments of supernatural horror in Gull’s mysticism, it is the book’s grimy realism that is far more terrifying. London in the late 1880s is no place you want to be, especially if you are poor, especially if you are a woman. The city is its own character, a labyrinth larded with ancient secrets the inhabitants of which cannot hope to plumb. Despite the nineteenth century’s claims for enlightenment and rationality, this London is bizarrely cruel and deeply unfair. Campbell’s style evokes this London and its denizens with a surreal brilliance; his dark inks are by turns exacting and then erratic, concentrated and purposeful and then wild and severe. The art is somehow both rich and stark, like the coal-begrimed London it replicates. Although Moore has much to say, he allows Campbell’s art to forward the plot whenever possible. Moore is erudite and fascinating; even when one of his characters is lecturing us, it’s a lecture we want to hear. His ear for dialog and tone lends great sympathy to each of the characters, especially the unfortunate women who must turn to prostitution to earn their “doss” money. And while Abberline’s frustrations at having to solve a crime that no higher-ups want solve make him the hero of this story, Gull’s mystic madness makes him the narrative’s dominant figure. Rereading this time, I realized there is no character he reminds me of as much as Judge Holden from Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. I’m also reading Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent now, a book that dovetails neatly with From Hell, both in its time and setting, but also in its exploration of social unrest and duplicitous authority. Both novels feature detectives fighting a complacent system, and both novels feature a working class that threatens to erupt in socialist or anarchist rebellion.

From Hell is a fantastic starting place for anyone interested in Moore’s work, more self-contained than his comics that reimagine superhero myths, like Watchmen or Swamp Thing, and more satisfying and fully achieved than Promethea or V Is for Vendetta. Be forewarned that it is a graphic graphic novel, although I do not believe its violence is gratuitous or purposeless. Indeed, From Hell aspires to remark upon the futility and ugliness of cyclical violence, and it does so with wisdom and verve. Highly recommended.

The film adaptations of David Peace‘s Red Riding quartet make their American debut this weekend. The films look pretty cool — kinda like Zodiac. The screen adaptations drop the 1977 segment of Peace’s original quartet, opting instead for the trilogy treatment. You can read Manohla Dargis’s detailed review for The New York Times here and Keith Phipps favorable review at the AV Club here. Trailer:

I’m about 60 pages away from finishing Roberto Bolaño’s posthumous magnum opus, 2666, an astounding, shocking book that you should pick up right now and start reading, unless, of course, you hate the idea of getting hopelessly addicted to a book that coerces you to read it, that lingers in the back of your mind and gut, beckoning, calling you, even as you should be working or spending time with your family or doing errands or chores, etc. But otherwise: read it. A proper review forthcoming.

Anyway. The backbone of the plot, or, rather, the peripheral story that haunts the plot(s) of this massive, heavy novel, involves a seemingly endless string of largely unsolved murders in the fictional Mexican border city of Santa Teresa. An ugly industrial town in the Sonora Desert, Santa Teresa is a thinly disguised stand-in for Ciudad Juárez, where over the past 15 years over 400 young women have been raped and killed, their murders unsolved. While searching the gruesome real-life back story that informs Bolaño’s masterpiece, I came across Fadek’s eerie and sympathetic images of Juárez (this background story on Fadek and the Juárez photos is also quite good). Fadek aims clearly to draw attention to these underreported crimes, but his photographs also capture the doom and foreboding that looms in the blood of 2666. Those who’ve read the novel will no doubt find them evocative of the fourth book of 2666, “The Part About the Crimes,” and those who are flirting with undertaking Bolaño’s big book may find their interest redoubled. In any case, Fadek’s photojournalism is well worth a look. Great stuff.