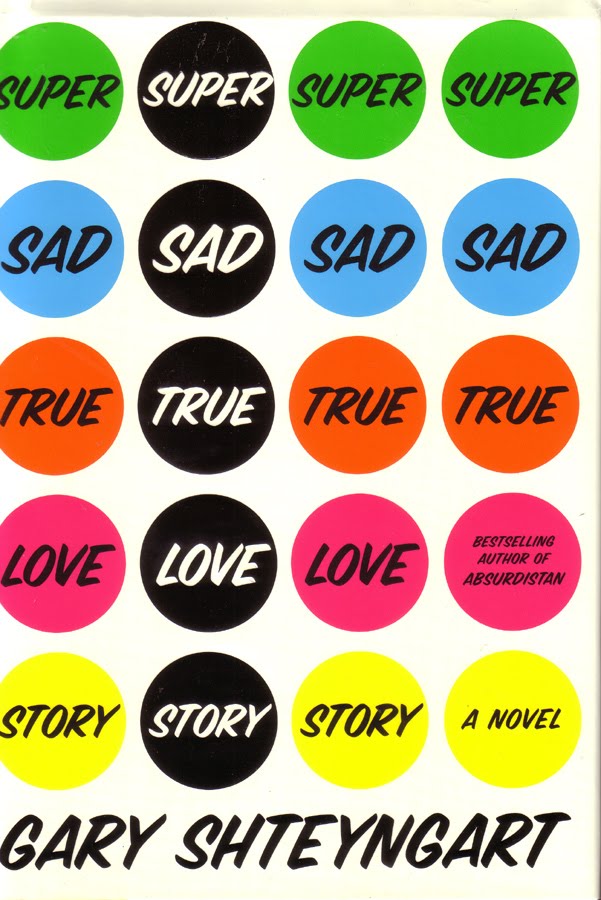

At a certain point, I was inclined to write a thoughtful review of Gary Shteyngart’s much-lauded, truly awful novel Super Sad True Love Story, the kind of review that might try to weigh Shteyngart’s choked May-December romance against its dystopian background. That was a few chapters in, a point at which I’d gotten past the realization that Shteyngart was going to do nothing new with the dystopian genre I so love, yet still early enough for me to think that he might have something to say about American culture and politics in the early 21st century. There’s nothing there, though — Super Sad True Love Story subscribes to the normal dystopian program of synthesizing 1984 and Brave New World through a contemporary lens, yet what we’re left with is Shteyngart’s observation that people might not like to read as much as they used to.

At a certain point, I was inclined to write a thoughtful review of Gary Shteyngart’s much-lauded, truly awful novel Super Sad True Love Story, the kind of review that might try to weigh Shteyngart’s choked May-December romance against its dystopian background. That was a few chapters in, a point at which I’d gotten past the realization that Shteyngart was going to do nothing new with the dystopian genre I so love, yet still early enough for me to think that he might have something to say about American culture and politics in the early 21st century. There’s nothing there, though — Super Sad True Love Story subscribes to the normal dystopian program of synthesizing 1984 and Brave New World through a contemporary lens, yet what we’re left with is Shteyngart’s observation that people might not like to read as much as they used to.

Obligatory plot summary: it’s America a few decades down the line–not enough to account for the change that Shteyngart proposes–an America under Bipartisan rule, a country without an elected President, at war with Venezuela, heavily indebted to China, and essentially ruled by a corporatocracy. People no longer read, they only scan data from their ever-present “äppäräti,” screen media devices they are addicted to through which they shamelessly broadcast every last piece of personal data. Sound familiar? Sure. (Those damn kids with their Facebooks!)

Shteyngart’s hero is Lenny Abramov, son of immigrant Russian Jews. Lenny works for Post-Human Services, a company that aims to extend human life indefinitely– as long as you’re very, very rich. This is Lenny’s obsession. For some reason, never fully explained (although painfully and boringly explored) Lenny wants to live forever. I suppose Shteyngart is trying to parody America’s obsession with youthfulness, only the parody is not funny and never insightful. Lenny meets a Korean-American girl named Eunice Park while spending some Bohemian time in Italy. Eunice is twenty years his junior, yet Lenny falls madly for her right away, for no good reason, at least not for any reason that we, the readers, are given to understand. It’s real old-white-boy-meets-young-Asian-girl-territory, which Shteyngart seems to understand yet seems too embarrassed (rightfully) to properly remark upon.

The backdrop of this romance is an American dystopia that Shteyngart wishes was as affecting as Alfonso Cuaron’s Children of Men. Hey, you know what? Watch Children of Men again instead of reading Shteyngart’s super boring book. And I think I won’t waste anymore time detailing Shteyngart’s super boring plot, a plot that seems to have no idea where its going, yet is, at all turns, overwhelmingly self-satisfied (and derivative). Shteyngart wants to write an end-of-America epic, yet nothing he says is worth re-remarking upon — yes, it seems like people are increasingly facile; yes, young people seem increasingly willing to forsake traditional ideas of privacy; yes, we owe the Chinese government some money. Sam Lipsyte does it all way better in The Ask, a book that doesn’t have to borrow its plot from every dystopian that came before it.

That Shteyngart has written a poor dystopian novel offends me at a literary-type level, but I’m also offended by his myopic regionalism, which, as I just mentioned, he tries to pass off as Americanism. For Shteyngart, New York City is America, and the (relatively) newly immigrated populations he places in his fictionalized NYC are far-more American than anyone else, particularly the dumb-ass-hick-redneck-Southerners he throws into the city as transplanted bad guys. Shteyngart’s Southern grotesques are mere props, barely thought out stereotypes that offend me as both a reader and a Southerner — and yet, they are just as facile as his leads.

Speaking of offensive and facile, there’s a moment at the end of the book when a critic takes the time to reflect on the publication of Lenny’s diaries and Eunice’s emails (not called “emails,” but Jesus Christ I’m not going to waste more time explaining the book’s silly recoding of contemporary culture) — it’s surreal in its tackiness, an overt act of literary criticism upon the rest of the book, one which attempts to focus a specific viewpoint upon the narrative proper. Like the rest of the book it fails miserably, and yet is indicative of Shteyngart’s needy, whiny program.

But why end negatively? There are plenty of great dystopian novels out there — Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake and The Year of the Flood, almost anything by William Burroughs, Disch’s Camp Concentration, Aldous Huxley’s sorely under-read Ape and Essence, Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, which understands that it’s always the end of the world, more or less all of Philip K. Dick, Riddley Walker, Cloud Atlas, shit, even Roberto Bolaño. Just don’t waste your time with Shteyngart’s super sorry book.