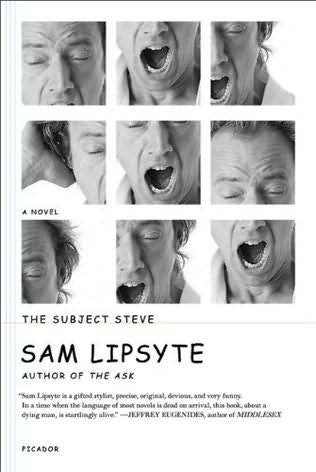

A few years ago, I wrote about cult novels, and, in trying to define them, I suggested that “a cult book is not (necessarily) a book about cults.” Sam Lipsyte’s first novel The Subject Steve is a cult novel about a cult, or at least heavily features a cult. Like many cult novels, there’s an apocalyptic scope to Steve, one in this particular case (or subject, if you will), that extends from the personal to the universal.

I’ll let Lipsyte’s compressed acerbic prose spell out the book’s central conflict—

The bad news was bad. I was dying of something nobody had ever died of before. I was dying of something nobody had ever died of before. I was dying of something absolutely, fantastically new. Strangely enough, I was in fine fettle. My heart was strong and my lungs were clean. My vitals were vital. Nothing was enveloping me or eating away at me or brandishing itself towards some violence in my brain. There weren’t any blocks or clots or seeps or leaks. My levels were good. My counts were good. All my numbers said my number wasn’t up.

The problem of death, or the problem of how to live a meaningful life against the specter of death, is of course an ancient conceit, and Lipsyte makes it the core of his book, upon which he hangs an often shaggy picaresque plot. The Subject Steve is post-modernist caustic satire in the good old vein of Candide; put another way, it’s just one damn thing happening after the next.

So, what are some of those things that happen? Steve (not his real name) is condemned to die of a disease with no name; he tries to make contact with his estranged wife and not-quite-a-genius daughter; he blows his life savings on hookers and blow; he heads upstate to a cult’s compound in the hopes of finding a cure to his unnamed (unnameable) disease; he suffers the cult’s sadistic practices; he escapes the cult’s sadistic practices; he reunites with his wife and daughter; he abandons his wife and daughter; he reunites with a new version of the cult somewhere in the Nevada desert; he becomes enslaved by the cult in the Nevada desert; he escapes the cult; &c. And he reflects on his life (and his death) repeatedly. I’ll let Steve reflect on his life at length, if for no other reason than to share more of Lipsyte’s marvelous prose—

And I was still dying, wasn’t I? Who would note? What had I ever noted? I’d taken my pleasures, of course, I’d eaten the foods of the world, drunk my wine, put this or that forbidden particulate in my nose until the room lit up like a festival town and all my friends, but just my friends, were seers. I’d seen the great cities, the great lakes, the oceans and the so-called seas, slept in soft beds and awakened to fresh juice and fluffy towels and terrific water pressure. I’d fucked in moonlight, sped through desolate interstate kingdoms of high broken beauty, met wise men, wise women, even a wise movie star. I’d lain on lawns that, cut, bore the scent of rare spice. I’d ridden dune buggies, foreign rails. I’d tasted forty-five kinds of coffee, not counting decaf.

I love this passage. In almost any other book I can think of, the final detail about coffee would puncture the passage’s inflation, serve as a comic anti-climax. In Lipsyte’s phrasing it’s both tragic and triumphant.

I don’t mean to gloss over the plot of The Subject Steve, but the book’s narrative, its sense of time, is so radically compressed (again, I think of the compression of Candide) that reading it is more like experiencing a rapid series of scenarios. I’m particularly fond of books like this, that seem to ramble and erupt in strange and unexpected moments. I think of Ellison’s Invisible Man or Woolf’s Orlando, but there’s also something of Aldous Huxley in Steve, that apocalyptic-comic axis, the satire of despair. The book is one of those pre-9/11 novels (forgive the phrase) that seems utterly prescient. Take the following observation for example—

Someday sectors of this city would make the most astonishing ruins. No pyramid or sacrificial ziggurat would compare to these insurance towers, convention domes. Unnerved, of course, or stoned enough, you always could see it, tomorrow’s ruins today, carcasses of steel teetered in a halt of death, half globes of granite buried like worlds under shards of street. Sometimes I pictured myself a futuristic sifter, some odd being bred for sexlessness, helmed in pulsing Lucite, stooping to examine an elevator panel, a perfectly preserved boutonniere.

The language here anticipates the Dead America that Lipsyte explores in his latest novel, The Ask, and reinforces a general argument I’d like to make, which is that Lipsyte is at heart a writer of dystopian fictions, fictions so contemporary that their dystopian nature becomes effaced.

These dystopian tropes coalesce in the frantic, hyperbolic ending of Steve, where our subject becomes the object of a bizarre cult’s ritual sadistic practices, all available via the panopticon of the internet. Lipsyte’s vision is of a post-human existence, a radical otherness of degradation through technological alienation. At this late moment in the book, the satire is so black that even Lipsyte’s tightest, pithiest sentences fail to elicit a laugh or a smile — indeed, I am almost certain that they are not intended to do so. Instead we are immersed in the apocalyptic horror of dehumanization (the book here reminded me of Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing, of all things, both in its desert location and in its gradual movement from sardonic humor to vivid terror).

Like any cult novel, or destined cult novel, The Subject Steve is Not For Everyone. Those looking for plot development and tidy endings will not find them here, and, if the tone of this review has not already made it clear, the book is extremely dark. But it’s also very, very funny, and there are few stylists working today who can match Lipsyte’s mastery of the sentence. Highly recommended.

The Subject Steve is now available in trade paperback from Picador.