IN THIS RIFF:

Introductions

Stories published between 1956 and 1959:

“Prima Belladonna”

“Escapement”

“The Concentration City”

“Venus Smiles”

“Manhole 69”

“Track 12”

“The Waiting Grounds”

“Now: Zero”

1. Introduction

I first read J.G. Ballard in high school. I found his work, somehow, after reading Burgess, Burroughs, and Vonnegut. I devoured many of his novels over the next few years, as well as several short story collections. One of these, The Best Short Stories of J.G. Ballard was particularly important to me. That collection—which I loaned to a friend who thought enough of it to never give it back—offers a concise overview of Ballard’s development as a writer, from the pulp sci-fi of his earliest days (“Chronopolis”) to his later evocations of ecological disaster and dystopia (“Billenium,” “The Terminal Beach”) to his more experimental work from The Atrocity Exhibition, stories that pointed toward one of his most famous books, Crash.

I hadn’t returned to Ballard since reading Super-Cannes when it came out a decade ago; at the time I recall being disappointed in the novel and filing it away with William Gibson’s recent efforts, which I found dull.

I’d been reading Donald Barthelme’s wonderful and strange short stories, and, rereading “Glass Mountain,” a story composed in a list, I remembered Ballard’s brilliant story “Answers to a Questionnaire” (from 1990’s War Fever). I tracked the story down in The Complete Short Stories of J.G. Ballard, read it, read a few more at random, and then decided to start at the beginning.

I’ll be reading and riffing on all 98 stories in the collection over the next few months—giving myself breaks for other stuff, of course (although Ballard’s stuff, especially the early stuff is really easy to read).

2. Another introduction

Martin Amis writes the introduction to the 2009 edition and of course manages to bring up his father Kingsley almost immediately. He talks about the times he (Martin) got to spend with Ballard. He points out that Ballard possessed “a revealingly weak ear for dialogue.” He suggests that Ballard could have been the love child of Saki and Jorge Luis Borges. He describes Ballard as “somehow uniquely unique.” He reminds me of why I usually skip introductions.

3. And Ballard’s introduction, from the 2001 first edition of the book

He situates his hero, his contemporary, and his forbear in the first paragraph:

Short stories are the loose change in the treasury of fiction, easily ignored beside the wealth of novels available, an over-valued currency that often turns out to be counterfeit. At its best, in Borges, Ray Bradbury and Edgar Allan Poe, the short story is coined from precious metal, a glint of gold that will glow for ever in the deep purse of your imagination.

He also tells us,

Curiously, there are many perfect short stories, but no perfect novels.

I agree, except for the adverb there.

Did Ballard’s sensibilities gel with the sci-fi fans who read the pulp mags his early stories were published in?

I was interested in the real future that I could see approaching, and less in the invented future that science fiction preferred.

In the final lines of his introduction he describes his oeuvre and addresses criticisms that there’s so much damn analog tech in his stuff:

Vermilion Sands isn’t set in the future at all, but in a kind of visionary present – a description that fits the stories in this book and almost everything else I have written. But oh for a steam-powered computer and a wind-driven television set. Now, there’s an idea for a short story.

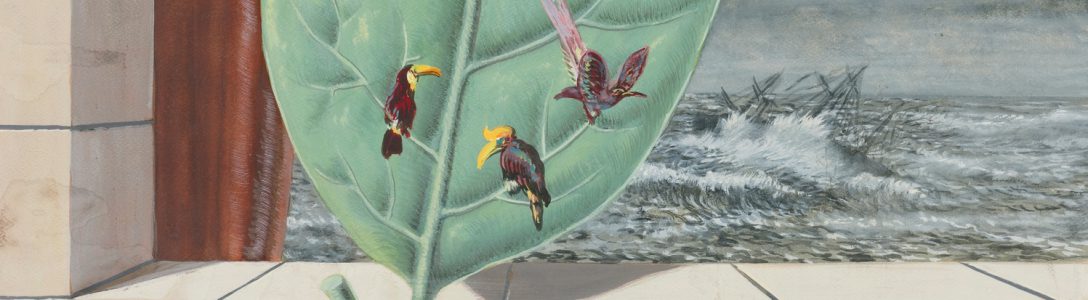

Vermilion Sands, the strange resort town where Ballard set over a half-dozen of his tales, is the setting of the first and fourth tales in the collection.

4. “Prima Belladonna” (1956) / “Venus Smiles” (1957)

Ballard already had a distinct setting in mind to play out his future-nowisms. That early stories “Prima Belladonna” and “Venus Smiles” are both in set in Vermilion Sands is maybe the most interesting thing about them. “Prima Belladonna” is never better than its first line:

I first met Jane Ciracylides during the Recess, that world slump of boredom, lethargy and high summer which carried us all so blissfully through ten unforgettable years, and I suppose that may have had a lot to do with what went on between us.

Ballard has the good sense to leave that cryptic reference to “the Recess” unexplained, or at least underexplained throughout the story—exposition is usually the worst aspect of pulp sci-fi. Still, the story is hardly one of his best. I’m guessing Roger Corman must have read it though, as his film Little Shop of Horrors (1960) seems to owe it a certain debt.

“Venus Smiles” is also set in Vermilion Sands, and it also takes music—sound—as its major motif (several of Ballard’s early stories do). Ballard strives to do too much in the story—he wants to criticize public attitudes about art, sculpture, music, etc., and also name drop John Cage to bolster his avant garde bona fides. Both stories drag, weighed down by Ballard’s clunky similes and bad dialogue (dear lord I’m agreeing with Amis here!). What’s most frustrating is knowing that Ballard is just a decade away from finding a rhetorical style to match the content of his ideas.

5. “Escapement” (1956)

The story of a man who realizes he is stuck in a time loop, repeating the same actions, “Escapement” is particularly frustrating. The stakes are incredibly low—the domestic scene of a married couple watching TV on a couch begs for darker treatment—and the reader figures out what’s going on way before the narrator. Time is clearly a major motif for Ballard, but his earliest published treatment of it is not especially inspiring. (I realize writing this what an ass I sound like: look, I know this is early work, pulp fiction—my frustration is that I want it to be better—or at least more abbreviated.

6. “The Concentration City” (1957)

“The Concentration City” finally sees Ballard in stronger territory, here exploring one of his favorite dystopic tropes—overpopulation—via one of his favorite conceits—the intrepid and intellectually curious young man. “The Concentration City” also showcases some early experimental touches in its opening paragraphs:

Noon talk on Millionth Street:

‘Sorry, these are the West Millions. You want 9775335th East.’

‘Dollar five a cubic foot? Sell!’

‘Take a westbound express to 495th Avenue, cross over to a Redline elevator and go up a thousand levels to Plaza Terminal. Carry on south from there and you’ll find it between 568th Avenue and 422nd Street.’

‘There’s a cave–in down at KEN County! Fifty blocks by twenty by thirty levels.’

‘Listen to this – “PYROMANIACS STAGE MASS BREAKOUT! FIRE POLICE CORDON BAY COUNTY!”

‘It’s a beautiful counter. Detects up to .005 per cent monoxide. Cost me three hundred dollars.’

‘Have you seen those new intercity sleepers? They take only ten minutes to go up 3,000 levels!’

‘Ninety cents a foot? Buy!’

The story follows up on these early notes, using the initially-estranging material to tell the story of a seemingly-infinite city; our young hero of course wants to bust out. Ballard also gives us an early prototype of what will be one of his major conventions: the green-zone/danger-zone split:

‘City Authority are starting to seal it off,’ the man told him. ‘Huge blocks. It’s the only thing they can do. What happens to the people inside I hate to think.’ He chewed on a sandwich. ‘Strange, but there are a lot of these black areas. You don’t hear about them, but they’re growing. Starts in a back street in some ordinary dollar neighbourhood; a bottleneck in the sewage disposal system, not enough ash cans, and before you know it a million cubic miles have gone back to jungle. They try a relief scheme, pump in a little cyanide, and then – brick it up. Once they do that they’re closed for good.’

No exit!

7. “Manhole 69” (1957)

Despite its unfortunate name, “Manhole 69” is perfect early Ballard. The story follows three men in an experimental group who have undergone a surgery that eliminates their ability to sleep. The story is precise and concise; Ballard seems comfortable here (“comfortable” is not a very Ballardian word, but hey…)—he sets up his experiment and then lets his principals carry it out. The story’s heavy Jungian vibe resurfaces a few years later in Ballard’s early novel The Drowned World.

“Manhole 69” is the first of the 98 stories here I’d put in a collection I’ll tentatively call The Essential Short Stories of J.G. Ballard.

8. “Track 12” (1958)

While “Track 12” is hardly perfect, its concision and focus do it many favors. Again, we find Ballard playing with sound—particularly something called “microsonics”:

Amplified 100,000 times animal cell division sounds like a lot of girders and steel sheets being ripped apart – how did you put it? – a car smash in slow motion. On the other hand, plant cell division is an electronic poem, all soft chords and bubbling tones. Now there you have a perfect illustration of how microsonics can reveal the distinction between the animal and plant kingdoms.

As is often the case, Ballard has an idea that fascinates him (“microsonics,” here) and simply constructs a story to deliver that idea. Or, rather, rips off a story—and Ballard has the good sense to steal from the best. “Track 12” is a fairly straightforward Edgar Allan Poe ripoff, a revenge tale recalling “The Cask of Amontillado,” and if the reader seems to guess where everything is going before the victim, well, it works here.

9. “The Waiting Grounds” (1959)

Ballard is better at inner space than outer space. “The Waiting Grounds” seems like a bait and switch, or at least I imagine many meat and potatoes SF fans might have felt that way. Ballard has his hero head to some distant planet, only to spend most of that trip in his own mind. And oh what a trip! The story’s central set piece anticipates the final scenes of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey as Ballard sends his hero through “deep time”:

Deep Time: 10,000,000,000 mega–years. The ideation–field has now swallowed the cosmos, substituted its own dynamic, its own spatial and temporal dimensions. All primary time and energy fields have been engulfed. Seeking the final extension of itself within its own bounds the mantle has reduced its time period to an almost infinitesimal 0.00000000… n of its previous interval. Time has virtually ceased to exist, the ideation–field is nearly stationary, infinitely slow eddies of sentience undulating outward across its mantles.

The frame Ballard builds to deliver his idea is clunky, but I suppose in those days one could make a sort of living writing stories for magazines, and maybe more words meant more moolah. Again, this story points to the Jungian themes that Ballard would explore in greater depth in The Drowned World.

10. “Now: Zero” (1959)

Here is the first paragraph of “Now: Zero,” the last story of Ballard’s to be published in the 1950s:

You ask: how did I discover this insane and fantastic power? Like Dr Faust, was it bestowed upon me by the Devil himself, in exchange for the deed to my soul? Did I, perhaps, acquire it with some strange talismanic object – idol’s eyepiece or monkey’s paw – unearthed in an ancient chest or bequeathed by a dying mariner? Or, again, did I stumble upon it myself while researching into the obscenities of the Eleusinian Mysteries and the Black Mass, suddenly perceiving its full horror and magnitude through clouds of sulphurous smoke and incense?

No doubt, dear reader, you immediately detect Edgar Allan Poe all over this piece, and you’re not wrong. The story is mostly interesting as a style exercise—namely, Ballard doing Poe—but its cheesiness and predictability drowns out any humor. But again, these are the complete short stories—not just the perfect exercises.

11. On the horizon:

The early 1960s! “Chronopolis”! “The Overloaded Man”! “Billenium”! You are encouraged to play along.

PREVIOUSLY:

PREVIOUSLY: