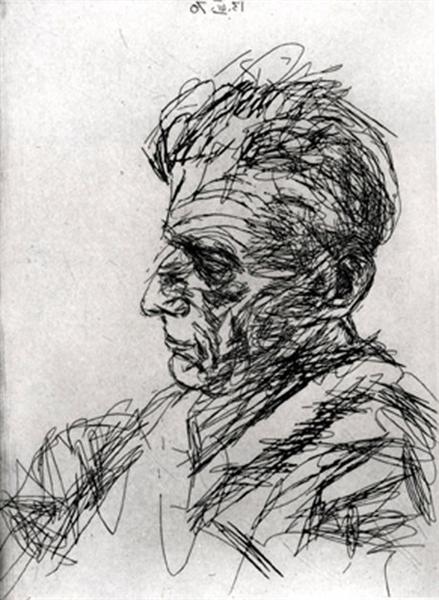

Sitting in the wing chair, I reflected that I had pretended to be shocked by Joana’s suicide and pretended to accept the Auersbergers’ invitation to their artistic dinner. When I accepted it I was only pretending, I now thought, yet in spite of this I had acted upon it. The idea is nothing short of grotesque, I thought, yet at the same time it amused me. Actually I’ve always dissembled with the Auersbergers, I thought, sitting in the wing chair, and here I am again, sitting in their wing chair and dissembling once more: I’m not really here in their apartment in the Gentzgasse, I’m only pretending to be in the Gentzgasse, only pretending to be in their apartment, I said to myself. I’ve always pretended to them about everything—I’ve pretended to everybody about everything. My whole life has been a pretense, I told myself in the wing chair—the life I live isn’t real, it’s a simulated life, a simulated existence. My whole life, my whole existence has always been simulated—my life has always been pretense, never reality, I told myself. And I pursued this idea to the point at which I finally believed it. I drew a deep breath and said to myself, in such a way that the people in the music room were bound to hear it: You’ve always lived a life of pretense, not a real life—a simulated existence, not a genuine existence. Everything about you, everything you are, has always been pretense, never genuine, never real. But I must put an end to this fantasizing lest I go mad, I thought, sitting in the wing chair, and so I took a large gulp of champagne.

From Thomas, Bernhard’s novel 1984 Woodcutters; English translation by David McLinktock.