Watch the Cream of Slovene analyze some film in this excerpt from The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology. (Via.)

Month: September 2013

Portrait of a Stout Man — Master of Flémalle

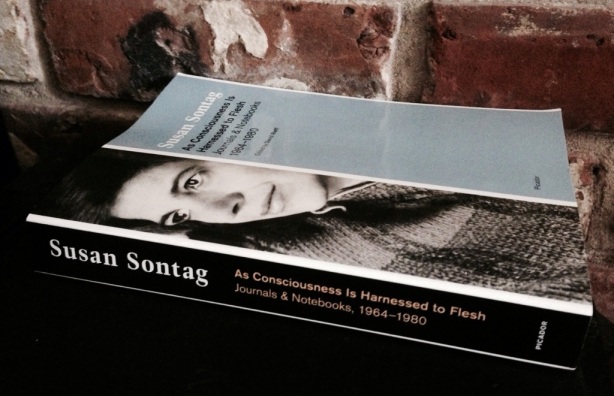

“Recycling one’s own life with books” |Thirteen Notes on Susan Sontag’s Notebook Collection, As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh

1. “In my more extravagant moments,” writes David Rieff in his introduction to Susan Sontag’s As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh, “I sometimes think that my mother’s journals, of which this is the second of three volumes, are not just the autobiography she never got around to writing…but the great autobiographical novel she never cared to write.”

2. In my review of Reborn, the first of the trilogy Rieff alludes to, I wrote, “Don’t expect, of course, to get a definitive sense of who Sontag was, let alone a narrative account of her life here. Subtitled Journals & Notebooks 1947-1963, Reborn veers closer to the “notebook” side of things.”

As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh is far closer to the ‘notebook’ side of things too, which I think most readers (or maybe I just mean me here) will appreciate.

3. I mean, this isn’t the autobiographical novel that Rieff suggests it might be (except of course it is).

Consciousness/Flesh offers something better: access to Sontag’s consciousness in its prime, not quite ripe, but full, heavy, bursting with intellectual energy, her mind attuned to (and attuning) the tumult of the time the journals cover, 1964 through 1980.

It’s an autobiography stripped of the pretense of presentation; it’s a novel stripped of the pretense of storytelling.

4. Sontag’s intellect and spirit course through the book’s 500 pages, eliding any distinction between lives personal and professional. “What sex is the ‘I’?” she writes, “Who has the right to say ‘I’?” The journals see her working through (if not resolving, thankfully) such issues.

5. An entry from late 1964, clearly background for Sontag’s seminal essay “Notes on Camp” (itself a series of notes), moves through a some thoughts on artists and poets, from Warhol to Breton to Duchamp (“DUCHAMP”) to simply “Style,” which, Rieff’s editorial note tells us, has a box drawn around it. The entry then moves to define

Work of Art

An experiment, a research (solving a “problem”) vs. form of a play

—before turning to a series of notes on the films of Michelangelo Antonioni.

6. A page or two later (1965) delivers the kind of gold vein we wish to discover in author’s notebooks:

PLOTS & SITUATIONS

Redemptive friendship (two women)

Novel in letters: the recluse-artist and his dealer a clairvoyant

A voyage to the underworld (Homer, Vergil [sic], Steppenwolf)

Matricide

An assassination

A collective hallucination (Story)

A theft

A work of art which is really a machine for dominating human beings

The discovery of a lost mss.

Two incestuous sisters

A space ship has landed

An ageing movie actress

A novel about the future. Machines. Each man has his own machine (memory bank, codified decision maker, etc.) You “play the machine. Instant everything.

Smuggling a huge art-work (painting? Sculpture?) out of the country in pieces—called “The Invention of Liberty”

A project: sanctity (based on SW [Simone Weil]—with honesty of Sylvia Plath—only way to solve sex “I” is talk about it

Jealousy

7. The list above—and there’s so much material like it in Consciousness/Flesh—is why I love author’s notebooks, We get to see the raw material here and imagine along with the writer (if we choose), free of the clutter and weight of execution, of prose, of damnable detail.

There’s something joyfully cryptic about Sontag’s notes, like the solitary entry “…Habits of despair” in late July of 1970—or a few months later: “A convention of mutants (Marvel comics).”

If we wish we can puzzle the notes out, treat them as clues or keys that fit to the work she was publishing at the time or to the personal circumstances of her private life. Or (and to be clear, I choose this or) we can let these notes stand as strange figures in an unconventional autobiographical novel.

8. Those looking for more direct material about Sontag’s life (and really, why do you want more and what more do you want?) will likely be disappointed—everything here is oblique (lovely, lovely oblique).

Still, there are moments of intense personal detail, like this 1964 entry where Sontag describes her body:

Body type

- Tall

- Low blood pressure

- Needs lots of sleep

- Sudden craving for pure sugar (but dislike desserts—not a high enough concentration)

- Intolerance for liquor

- Heavy smoking

- Tendency to anemia

- Heavy protein craving

- Asthma

- Migraines

- Very good stomach—no heartburn, constipation, etc.

- Negligible menstrual cramps

- Easily tired by standing

- Like heights

- Enjoy seeing deformed people (voyeuristic)

- Nailbiting

- Teeth grinding

- Nearsighted, astigmatism

- Frileuse (very sensitive to cold, like hot summers)

- Not very sensitive to noise (high degree of selective auditory focus)

There’s more autobiographical detail in that list than anyone craving a lurid expose could (should) hope for.

9. For many readers (or maybe I just mean me here) Consciousness/Flesh will be most fascinating as a curatorial project.

Sontag offers her list of best films (not in order),her ideal short story collection, and more. The collection often breaks into lists—like the ones we see above—but also into names—films, authors, books, essays, ideas, etc.

10. At times, Consciousness/Flesh resembles something close to David Markson’s so-called “notecard” novels (Reader’s Block, This Is Not a Novel, Vanishing Point, The Last Novel):

Napoleon’s wet, chubby back (Tolstoy).

and

Wordsworth’s ‘wise passiveness.’

and

Nabokov talks of minor readers. ‘There must be minor readers because there are minor writers.’

and

Camus (Notebooks, Vol. II): ‘Is there a tragic dilettante-ism?'”

and

‘To think is to exaggerate.’ — Valéry.

and so on…

11. Sometimes, the lists Sontag offers—

(offers is not the right verb at all here—these are Sontag’s personal journals and notebooks, her private ideas, material never intended for public consumption, but yes we are greedy, yes; and some of us (or maybe I just mean me here) are greedier than others, far more interested in her private ideas and notes and lists than the essays and stories and novels she generated from them—and so no, she didn’t offer this, my verb is all wrong)

—sometimes Sontag [creates/notes/generates] very personal lists, like “Movies I saw as a child, when they came out” (composed 11/25/65). There’s something tender here, imagining the child Sontag watching Fantasia or Rebecca or Citizen Kane or The Wizard of Oz in the theater; and then later, the adult Sontag, crafting her own lists, making those connections between past and present.

12. While Reborn showcased the intimate thoughts of a nascent (and at times naïve) intellect, Consciousness/Flesh shows us an assured writer at perhaps her zenith. In September of 1975, Sontag defines herself as a writer:

I am an adversary writer, a polemical writer. I write to support what is attacked, to attack what is acclaimed. But thereby I put myself in an emotionally uncomfortable position. I don’t, secretly, hope to convince, and can’t help being dismayed when my minority taste (ideas) becomes majority taste (ideas): then I want to attack again. I can’t help but be in an adversary relation to my own work.

13. Readers looking for a memoir or biography might be disappointed in Consciousness/Flesh; readers who seek to scrape its contours for “wisdom” (or worse, writing advice) should be castigated.

But As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh will reward those readers who take it on its own terms as an oblique, discursive (and incomplete) record of Sontag’s brilliant mind.

I’ll close this riff with one last note from the book, a fitting encapsulation of the relationship between reader and author—and, most importantly, author-as-reader-and-rereader:

Recycling one’s own life with books.

As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh is new in trade paperback from Picador; you can read excerpts from the book at their site.

Melancholy and Mystery of a Street — Ulf Puder

“Lines” — William Carlos Williams

Who Is Sleeping On My Pillow — Mamma Andersson

Brilliantly — Theodor Severin Kittelsen

Stop Making Sense — Talking Heads

Frog Wars (Detail) — Mu Pan

“My First Romance” — Lafcadio Hearn

“My First Romance” by Lafcadio Hearn

There has been sent to me, across the world, a little book stamped, on its yellow cover, with names of Scandinavian publishers – names sounding of storm and strand and surge. And the sight of those names, worthy of Frost-Giants, evokes the vision of a face – simply because that face has long been associated, in my imagination, with legends and stories of the North – especially, I think, with the wonderful stories of Björnstjerne Björnson.

It is the face of a Norwegian peasant-girl of nineteen summers – fair and ruddy and strong. She wears her national costume: her eyes are grey like the sea, and her bright braided hair is tied with a blue ribbon. She is tall; and there is an appearance of strong grace about her, for which I can find no word. Her name I never learned, and never shall be able to learn; – and now it does not matter. By this time she may have grandchildren not a few. But for me she will always be the maiden of nineteen summers – fair and fresh from the land of the Hrimthursar – a daughter of gods and Vikings. From the moment of seeing her I wanted die for her; and I dreamed of Valkyrja and of Vala-maids, of Freyja and of Gerda. . . .

She is seated, facing me, in an American railroad-car – a third-class car, full of people whose forms have become indistinguishably dim in memory. She alone remains luminous, vivid: the rest have faded into shadow – all except a man, sitting beside me, whose dark Jewish face, homely and kindly, is still visible in profile. Through the window on our right she watches the strange new world through which we are passing: there is a trembling beneath us, and a rhythm of thunder, while the train sways like a ship in a storm.

An emigrant-train it is; and she, and I, and all those dim people are rushing westward, ever westward – through days and nights that seem preternaturally large – over distances that are monstrous. The light is of a summer day; and shadows slant to the east.

The man beside me says:

“She must leave us tomorrow; – she goes to Redwing, Minnesota. . . . You like her very much? – yes, she’s a fine girl. I think you wish that you were also going to Redwing, Minnesota?”

I do not answer. I am angry that he should know what I wish. And it is very rude of him, I think, to let me know that he knows.

Mischievously, he continues:

“If you like her so much, why don’t you talk to her? Tell me what you would like to say to her; and I’ll interpret for you. . . . Bah! you must not be afraid of the girls!”

Oh! – the idea of telling him what I should like to say to her! . . . Yet it is not possible to see him smile, and to remain vexed with him.

Anyhow, I do not feel inclined to talk. For thirty-eight hours I have not eaten anything; and my romantic dreams, nourished with tobacco-smoke only, are frequently interrupted by a sudden inner aching that makes me wonder how long I shall be able to remain without food. Three more days of railroad travel – and no money! . . . My neighbor yesterday asked me why I did not eat; – how quickly he changed the subject when I told him! Certainly I have no right to complain: there is no reason why he should feed me. And I reflect upon the folly of improvidence.

Then my reflection is interrupted by the apparition of a white hand holding out to me a very, very large slice of brown bread with an inch-thick cut of yellow cheese thereon; and I look up, hesitating, into the face of the Norwegian girl. Smiling, she says to me, in English, with a pretty, childish accent:

“Take it, and eat it.”

I take it, I devour it. Never before nor since did brown bread and cheese seem to me so good. Only after swallowing the very last crumb do I suddenly become aware that, in my surprise and hunger, I forgot to thank her. Impulsively, and at the wrong moment, I try to say some grateful words.

Instantly, and up to the roots of her hair, she flushes crimson: then, bending forward, she puts some question in a clear sharp tone that fills me with fear and shame. I do not understand the question: I understand only that she is angry; and for one cowering moment my instinct divines the power and the depth of Northern anger. My face burns; and her grey eyes, watching it burn, are grey steel; and her smile is the smile of a daughter of men who laugh when they are angry. And I wish myself under the train – under the earth – utterly out of sight forever. But my dark neighbor makes some low-voiced protest – assures her that I had only tried to thank her. Whereat the level brows relax, and she turns away, without a word, to watch the flying landscape; and the splendid flush fades from her cheek as swiftly as it came. But no one speaks: the train rushes into the dusk of five and thirty years ago . . . and that is all!

. . . What can she have imagined that I said? . . . My swarthy comrade would not tell me. Even now my face burns again at the thought of having caused a moment’s anger to the kind heart that pitied me – brought a blush to the cheek of the being for whose sake I would so gladly have given my life . . . But the shadow, the golden shadow of her, is always with me; and, because of her, even the name of the land from which she came is very, very dear to me.

Not to Be Reproduced — René Magritte

“Terminator Too” — Tom Clark

“Terminator Too” by Tom Clark—

Poetry, Wordsworth

wrote, will have no

easy time of it when

the discriminatingpowers of the mind

are so blunted that

all voluntary

exertion dies, andthe general

public is reduced

to a state of near

savage torpor, morose,stuporous, with

no attention span

whatsoever; nor will

the tranquil rustlingof the lyric, drowned out

by the heavy, dull

coagulation

of persons in cities,where a uniformity

of occupations breeds

cravings for sensation

which hourly visualcommunication of

instant intelligence

gratifies like crazy,

likely survive this age.

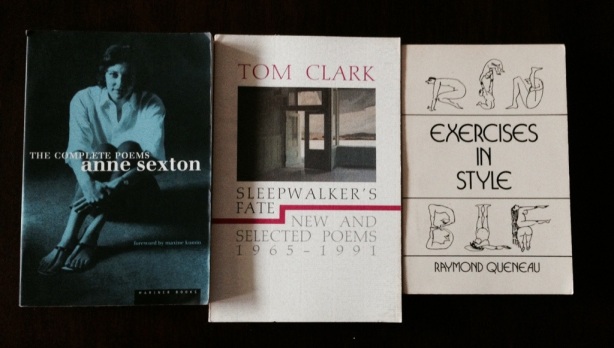

Clark/Queneau/Sexton (Books Acquired, 9.27.2013)

“Fate,” Tom Clark:

“Syncope,” Raymond Queneau:

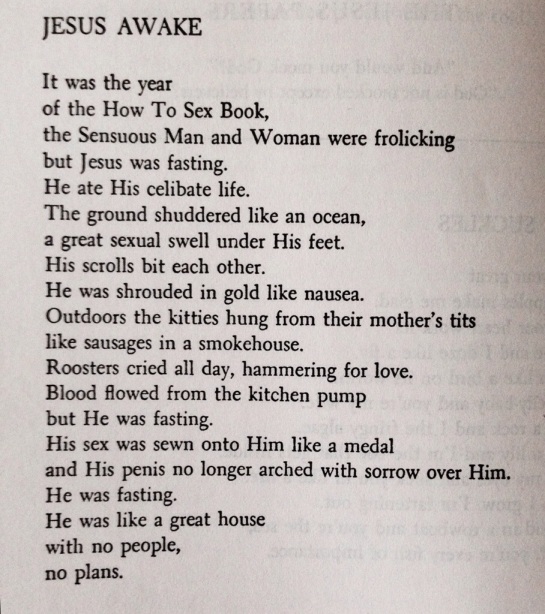

“Jesus Awake,” Anne Sexton:

“A Little Ramble” — Robert Walser

Allegory of Air — Jean-Baptiste Oudry

Ingrid Bergman’s Home Movies

The War Between Frogs and Mice — Theodor Severin Kittelsen