Rainer J. Hanshe’s new book Shattering the Muses is comprised of citations, short histories, poems, complaints and lamentations, anecdotes, essays, etchings, manipulated photographs, photographs of old documents, ink and enamel drawings, coal and ash pictures, and other media. His co-conspirator on the project is Federico Gori who provides original art for Shattering the Muses. Here are two of nine depictions by Gori of muses that open (in a sense) the narrative:

The books is ten inches tall, seven inches wide, and one inch thick. It contains 370 pages, many of them illustrated, several blank, and five that are completely black. There are at least four fonts (and more languages than that, although the book is primarily in English).

Have I lingered over form too long here? It’s difficult to describe the content of Shattering the Muses (which often foregrounds the “narrative’s” form).

Or maybe description isn’t so difficult—perhaps we can rely on the book to name its own central problem. The question that threads through Shattering the Muses is “Beware the Book?”

Let’s look at a few examples:

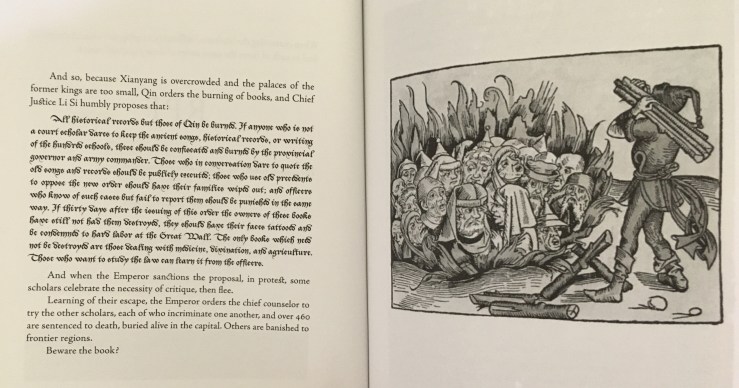

Above, we read an account—with its own embedded quotation—of The First Emperor of Qin’s ordering, two hundred years or so before the birth of Christ, a grand burning of a great many books. The account ends with the question: “Beware the book?”

(Some historians remark that Quin Shi Huang caused to be buried alive 460 Confucian scholars).

On the opposing/facing page, a 1493 German woodcut depicts Jews being buried and burned alive, scapegoats for the Black Death plague. The woodcut provides an answer to the question: “Beware the book?”: No, beware the burners. The space between the two pages is a gap for the reader to cross. Put the pieces together.

Indeed, it is the reader’s task (task is not quite the right word) to put the pieces of Shattering together. Take the pages above, for example. A passage from Areopagitica, Milton’s defense of free speech, contends that books are “not absolutely dead things,” but rather extractions of the soul’s intellect. He compares them to “those fabulous dragon’s teeth” that Cadmus scattered by Athena’s command. Milton warns that “he who destroys a good book kills reason itself, kills the image of Life.”

The next page reproduces Johan Liss’s painting Apollo and Marsyas (c. 1627). The satyr Marsyas found and mastered the first aulos, an double-reed wind instrument cast away by Athena. (She didn’t like the shape her invention brought to her virgin cheeks). Marsyas challenged Apollo to an aulos contest and lost, natch. (Apollo’s daughters the Muses were the judges). Marsyas was subsequently flayed alive, his hide nailed to a tree. Victim for art’s sake.

(The first page of Shattering the Muses is a quote from Ovid’s Fasti. The lines describe Athena discarding her aulos: “Art is not worth this to me,” she says, seeing her reflected face deformed in the river as she produces the “sublime” music).

One more set of two pages, then. (It’s easier to show the book than to properly describe it in words. This is not a review). Above: Tadeusz Różewicz was a Polish poet who fought in the resistance movement against the Nazi occupation. He survived the war. His brother Janusz, also a poet, did not. He was executed by the Gestapo in 1944.

The facing page is a photograph of a scrap of one of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri manuscripts (specifically, P.Oxy. 67.4633). This scrap contains commentary on Homer’s Iliad, but is mostly famous because someone used it to wipe their ass. (A literary critic?)

However, Shattering the Muses is not entirely composed of loosely arranged but discontinuous fragments. Several narratives strand through the book. The most straightforward of these is the story of Renato Naso, who is the closest thing to a main character we’ll find here. When we’re introduced to him, we’re told that he’s “unknowingly putting his life in suspension…living in an eternal between.” He’s a hero (?) ripe for “rupture, fracture, and shattering.” (Perhaps if we take Shattering the Muses as a “novel” we could imagine that the events within take place in Naso’s stretched consciousness—a more secure place for such horrors than, uh, historical reality). When we first meet him, he’s leaving New York for Berlin, forced to abandon most of his books and store them in his brother’s garage. His brother’s house and garage are flooded by Hurricane Sandy, but his library miraculously survives. And yet the historical accounts of book burnings (and human burnings) cataloged in Shattering the Music attest that no library is ever safe. As Milton suggests, libricide and homicide are intertwined.

Hence, other background “characters” emerge more prominently than others in Shattering the Muses: Hitler, Mussolini, the Gestapo. The specter of the Nazis and the Holocaust weigh heavily here, heavier than the (many) other libriciders documented. Against this evil Hanshe gives us a resistance—a wonderful chapter lingers on Samuel Beckett, who’s escaped Occupied Paris to hide in the small village of Roussillon. There, “separated from his library…literary freedom erupts” for Beckett. Absence is a generative power.

Other figures resist through art, even if they perish in the horror, like Hungarian poet Miklós Radnóti, murdered by the Nazis near Győr and tossed into a mass grave. In a poetic turn, Hanshe notes “it is a daring Marsyas that he becomes, risking his flesh doubly before a merciless & savage Apollo, for he will not cast his aulos to the turf of the riverbank.” Deft touches like these link this “novel’s” motifs of beauty and destruction, art and murder.

A narrative forms too from more oblique strategies—a plague of mutating billboards, for instance, or spiderwebs of poetry. Handbills, demands, stray bits of philosophy. But maybe I’m back where I started—go all the way back to the title here: This is not a review of Shattering the Muses. I can’t properly parse it, really. It’s overwhelming—linguistically, philosophically, typographically, aesthetically. Intellectually is a word to use here. Hell. It’s a lot to digest all at once. Let me admit that I’m more interested in picking at it slowly. Hanshe’s put a lot of material on the table. It’s a rich meal.

Who is Shattering the Muses for? I hope that I’ve shared enough snippets to give you a sense of what (might be) happening here. I enjoyed it, and enjoy it more in the sense of a text to return to. At the same time, this book is clearly Not For Everyone. Shattering the Muses is an encyclopedic poem, a Choose Your Own Adventure story of aesthetic horror and loss. It’s not likely to cohere for you quickly and neatly, but it’s a weird joy to think (and feel) through.

Last word goes to the Text:

Beware the Book?

Beware the Purifiers!

Beware Libricide.